The mobility of capital, depending on one’s position, is a virtue or a vice. Since the onset of the Arab Spring, a lot of money has been moving in, out, and around the Middle East. In the classic liberal world, the mobility of money is governed by the market. In the real world however, politics has a say. Some of these politics have been about fear as Saudi and Emirati rulers have reportedly opened their checkbooks to assuage pressures on favored rulers and foment trouble for others. These moves did not come as much of a surprise. But somewhat more unexpected and commented upon by the media have been the responses of Western authorities essentially treating Libya’s sovereign wealth in the same manner as Mubarak’s and Ben Ali’s loot. Here is what is known from media reports.

First out of the gate, even ahead of post-revolutionary Tunisian and Egyptian requests, Swiss officials froze Ben Ali’s and Mubarak’s assets including those of close allies and family members. Clearly, the Swiss were weary of being the poster child for offshore laundering. The European Union and the United Nations eventually followed suit, but Washington has yet to respond publically to Cairo’s requests. However in the case of Libya, the US Treasury went further, utilizing a Soviet-sounding Ford Administration law, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, to freeze not only Qaddafi family assets but also billions of the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA). This extraordinary, first-ever seizure of a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) has implications not just for the sanctity of capital mobility but for the political health of the Gulf ruling families. After all, the bulk of their investments are held in the United States.

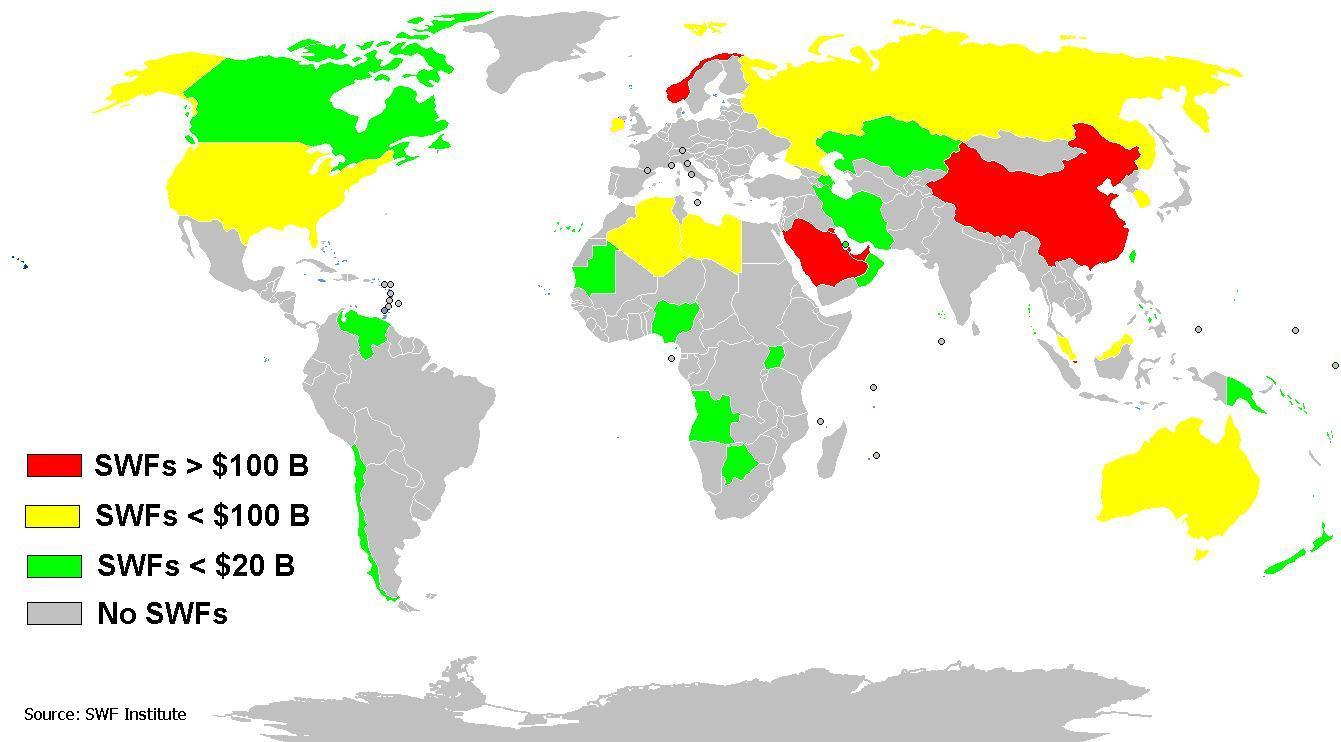

Because most of today’s SWFs operate like national security agencies, estimates of the location and size of their investments vary. However, the consensus is that Arab SWFs amount to around 1.5 trillion dollars or about half of all global SWF funds today. Oil exporters are the fourth largest holders of US Treasury Securities behind China, Japan, and the United Kingdom. It took some time to get to that level and like other firsts in the Gulf it started with Kuwait. In the 1950s, Kuwait established the first modern SWF in a small London office known as the Kuwait Investment Office (KIO), which later folded into the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) in 1982. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman followed in these early years with their own funds. Yet all were exclusively staffed with outside management expertise and were generally low profile domestic actors who invested small percentages of annual oil profits into Western government bonds. This last decade witnessed a flurry of new Arab SWFs established by Qatar, Algeria, Bahrain, and Libya. Meanwhile, the big three funds—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE --grew to become the world’s largest, even spinning off subsidiary SWF--like vehicles such as Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala.

[Sovereign wealth funds]

Conventional explanations for the growth of SWFs portray them as state institutions that promote diversification and prudent savings for posterity by investing oil profits overseas. Guided by professionalism and profit, advocates argue that such investment bootstraps a nation’s finances out of the inefficiencies of domestic oil patronage. In fact, SWFs were one of the first advertised remedies for the economic instabilities characteristic of oil-dependent economies. Rainy-day funds and diversification make sense. However, the evolution of Gulf Arab SWFs has been an essential piece of rentier politics, which starts and ends with regime survival. Internationally and domestically, uprising and regime overthrow are just the most recent threats to these political arrangements.

SWFs as International Politics

As Timothy Mitchell, Robert Vitalis, and Toby Jones have argued, global oil profits—the lifeblood of Arab SWFs—are based on two elements. These are a low elasticity of demand (meaning consumers cannot easily switch to other sources of energy) and a “system of scarcity” in which the abundance of oil is turned into a premium. Since the Gulf region accounts for most of the world’s proven oil reserves, the ruling families are the political linchpins of this system. Saudi extra production capacity, Emirati and Kuwaiti spot market selling (outside of OPEC quotas), and oil smuggling are all mechanisms to bolster or lessen scarcity. Since the 1970s, the issue for American leaders and bankers has been how to get those magnificent profits back to the US instead of elsewhere. Some history is needed to understand the role SWFs have come to play in addressing that task.

By the early 1970s, oil-producing states wrestled control of their resources from the major international oil companies, the so-called “seven sisters,” who had invented the system of scarcity. The ensuing rise of oil prices in 1973 posed a dilemma for Western economies as well as for the newly flush Gulf ruling families. Put simply, the massive and rapid oil revenues of the 1970s posed a dangerous imbalance to the global financial system. Oil producing countries could not import fast enough to offset the massive capital inflows. This meant that other developed countries, particularly the United States, would be forced to run massive trade deficits. Foreshadowing the financial crisis of 2008, central bankers in the United States feared this imbalance could dry up the domestic American banking system bringing lending to a halt. Then as now, the standard policy response would have been to buy less, save more, and endure a general decline in public welfare. Like today, US officials set that option aside. To the rescue came the forerunners of today’s SWFs, Gulf central banks and their ministries of finance.

In his provocative 1999 book, The Hidden Hand of American Hegemony: Petrodollar Recycling and International Markets, David Spiro argues that US officials cut a secret deal with Saudi monetary authorities to route oil profits into US government and bank instruments (known as petrodollar recycling) thereby alleviating imbalance without austerity. The scheme worked so well that in 1978 one account at the New York Federal Reserve Bank held seventy percent of all Saudi assets in the United States. Saudi success in resisting OPEC efforts to denominate oil prices in currencies other than the dollar was another important achievement for American economic hegemony. Though there is no smoking gun, Spiro raises good reasons to believe that US security assurances were offered to the Saudis, assurances later fulfilled through the Carter Administration’s Rapid Deployment Force and accelerated after the fall of the Iranian Shah. The flip side of the military coin was the financial modernization of the SWF.

Liberalization of international finance in the 1980s and 1990s set the stage for opaque and official Arab SWFs to replace the secret government-to-government deals of the 1970s. Proliferation of new investment mechanisms and deregulation of the American banking system in the 1990s positioned well-heeled banks and private hedge funds as the new middlemen for oil profits. Expansion of the financial profession in the United States and Europe offered young Arab SWFs “the professional staffs” and guidance to legitimate their investments in market terms. Solidification of regional trading zones like NAFTA and the EU incentivized SWFs to purchase investment houses and companies registered within the zones, thereby adding layers of authority to obscure accountability. As prestigious international investors, staffed with some of Europe’s and North America’s best finance experts, secret unilateral deals became proprietary investment, and old forms of petrodollar recycling expanded to direct investment in equities, real estate, and weapons systems. While shifts in the international system were integral to this new recycling system, changes within Gulf societies were equally consequential.

SWFs as Domestic Politics

Initially Kuwait and secondly the UAE both experienced crises that hastened their own SWF growth and reoriented their investment attention away from Europe and toward the United States. For Kuwait, a massive stock crash in 1981 followed by economic fallout from the Iraqi invasion a decade later forced the Al-Sabahs to liquidate unknown but likely significant portions of the KIA’s assets. This led Kuwaiti officials to increase investment in the KIA and bank those funds with their new protector, Washington. By contrast, very little of Kuwait’s petrodollar recycling in the 1970s found its way into the United States. For the UAE, the lesson was similar but came about as a result of the infamous Bank of Credit and Commerce International crisis.

The Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), one of the largest international banks of its day, was essentially the private reserve and unofficial SWF of Zayed Bin Sultan Al-Nahyan, first president of the UAE and ruler of Abu Dhabi. In the late 1970s, Emirati officials wishing to cement closer relations with the Carter Administration secretly invested BBCI funds in the National Bank of Georgia, then owned by President Jimmy Carter’s boyhood friend and former director of the Office of Management and Budget, Bert Lance. The bank would eventually collapse during the 1980s savings and loans crisis. In the course of investigations, regulators found links to the BBCI and the complex international laundering and crimes for which the bank became synonymous. An eventual Congressional report authored by Senators John Kerry and Hank Brown deeply embarrassed the rulers of Abu Dhabi, particularly chapter fourteen, “Abu Dhabi: BCCI`S Founding and Majority Shareholders,” which traced the BBCI’s connections to the ruling family and concluded that there was little distinction between ruler wealth and the wealth of the UAE. Coincidentally perhaps, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) founded in 1976, began its massive expansion in hiring and American investment after this crisis. By the mid-1990s Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, were building better-funded SWFs all directed primarily to the United States.

A second important domestic shift was the changing patterns of rent seeking and wealth creation. By the 1980s and 1990s, Gulf ruling family members and private sector elites were increasingly rich, not just by regional standards but globally. For example, family-owned construction firms like the Al-Kharafis of Kuwait and the Bin Ladens of Saudi Arabia feasted on public sector largess in the 1970s and by the 1990s had grown into international multi-service conglomerates. With the pie getting too big to ignore, ruling family members began crossing into the private sector in ways different from and more overt than the past. It was no longer prestigious to get rich simply through government service. Perceptions of the 1970s playboy prince did not comport with a new generation schooled at the best European and American private academies and universities.

The established patronage and distribution networks characteristic of rentier politics remained in place for the national populations, yet SWFs were a different story. They offered much more particular and profitable internationally prestigious rent seeking. Gradually, the distinction blurred between the original SWF design (external investments) and the typical state owned enterprise (domestic operation). For example, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala, Kuwait’s Equate, Dubai Ports, and Emirates Airlines, to name a few, have emerged as new kinds of hybrid enterprises that pursue external investment and profit, as well as bolster the centralization of economic privilege. Notwithstanding recent economic downturns, these enterprises are successful. They invest overseas and attract foreign direct investment at home. They also look a lot different than the traditional rent-seeking enterprises in terms of profit and employment. On the other hand, ruling family members and their allies command most of these entities in the same opaque ways that Al-Nahyans controlled the BCCI. In fact, international bankers who had competed to lend to whatever Dubai developers dreamed up in the 2000s did so because they believed local property companies were ruler owned, not because Gulf beachfront property is good collateral. When the bubble burst in 2009, it turned out that Dubai’s rulers would decide which borrowers were sovereign (repayment guaranteed) and which were private (repayment negotiated). What is sovereign and what is not seems to be in the eye of the beholder. Such shadows promote numerous opportunities for insider trading and high-level graft. Imagine the advantages in, say, having prior knowledge of the October 2008 Abu Dhabi and Qatari twelve-billion-dollar rescue of Barclays Bank. Or consider the particular gains wrung from firms and individuals competing to earn SWF investment. Evidence of this kind of collusion is hardly abundant, but when things go wrong, it is hard to hide.

Such was the situation for the loss and theft of nearly five billion dollars in Kuwaiti investments in Spain in the late 1980s and early 1990s. When the story broke in 1993, the losses made it the largest case of corruption in modern European history. Known as the “KIO scandal” (after the London office of the KIA), investigations revealed that Sheikh Fahad Mohammed Al-Sabah, the former head of the KIO in London, its general manager, and other associates used a shady Spanish intermediary and several Netherlands-based companies owned by the KIA to take personal commissions on transactions tied to Kuwait’s Spanish investments. Of the five billion dollars lost, nearly a fifth was stolen in this way. This pattern of disclosure only following losses too large to hush might have been broken with the 2011 uprisings and the subsequent seizure of Libyan assets.

The Last Chapter

Western financial and political circles welcomed the creation of the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA) in 2006 as evidence of Libya’s return from the wilderness. With forty billion dollars to spend, the LIA arrived with all the claims of professionalism and posterity that its Gulf cousins pioneered. What managed Libyan money was not as creepy as the BBCI or as obscure as KIA offshore companies. Nevertheless, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, and JPMorgan Chase interacted with the LIA in the same non-transparent ways. There was good reason to do so because Libya’s uprising has forced transparency of some of the books, and the results are not encouraging. Libyan assets placed in these firms reportedly lost billions at the same time some firms crafted close relations with figures in the Qaddafi regime. US officials are investigating Goldman Sachs for offering what might be bribes to LIA officials in Tripoli to assuage the losses and keep the business. Additionally, the firm admitted to hiring a brother of the former deputy of the LIA, though it claims no quid pro quo.

Ask a banker today at the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority or the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority about the politics of Arab SWFs and the answer is inevitably that of course Kuwaiti and Libyan investments are politically driven, but theirs are not. Non-disclosure agreements and compartmentalization make that line easier to maintain. However the claim does not square with the history of petrodollar recycling, the BCCI, the KIO scandal, and now the LIA. A great irony of global financial liberalization has to be that the most successful financial adapters have turned out to be the most political.