On the way back from Kafr Qasim, we turned off the highway in Ran’ana where, we were told we’d find the best Moroccan food in the country. We went into the first gas station we saw when we came into the town, and the Iraqi attendant there told us where our restaurant was. It’d been weeks since we’d had anything but local food, and as delicious as that could be, we were getting sick of the humous and tomatoes and thyme and parsley and eggplant and rice and flat bread. What we craved was bitter lemons, dried fruits, hot red pepper paste and couscous—anything that diverged from the seasonal norms of the Eastern Mediterranean. We crossed our fingers and went into the place people had recommended so much. We noticed that in the window they’d posted two reviews they’d received back in the 90s. The accompanying faded photos made it seem like another century.

We laughed when we walked inside because it had the same kitsch appeal that its counterparts everywhere did. Someone asked whether there was a single Moorish design team, dispatched from Paris or LA, every time someone somewhere in the world wanted to open a restaurant called “Casablanca” or “Fez.” This one was called, “Le Levant.” We thought the name was clever, though Khalil remarked the place should have been called "Le Ponant."

We were sat at a corner table, a low, round brass thing, partially sunk into the ground, surrounded by stuffed, round leather pillows. We looked around—we were the only ones in the place. Near us, to our right, was a parquet floor, equipped with some speakers and microphones, “for the obligatory belly dance performance later,” Hani quipped.

Our waiter, who turned out to be Yemeni, came over in full impeccable Maghrebi regalia—the puffy pants and gold pointy shoes, the snug, undersized blue jacket with gold buttons, and the tilting tarbouche, tassels dangling just so. He carried a shiny tin tray, with rolled-up steaming-hot white towels, which he ceremoniously handed to us with a pair of oversized tongs. He welcomed us in an overly formal way, and handed out our menus. When we told him that we didn’t read Hebrew, he began to speak to us in a salty English laced with distinct Scottish traces. When we asked him why and how, he told us he’d done a masters degree in Engineering at St. Anne’s, “fine lot of good that did me!”

He asked us where we were from, and when Nidal said, “Palestine,” he chuckled and said, “So that’s how it’ll be, eh?” He seemed to like our answer, though never mentioned it again. He came out and told us about all the specials, and then suggested that we order a variety of entrees served “Moroccan family style,” which meant we’d all eat from the same large platter. We ordered the lemon chicken and the lamb stew. Even though that was already too much for us, our waiter convinced us to also order the bastilla, “Which is what we’re famous for.”

While we were at it, we asked him for a bottle of mahiya. He recommended that we start out with beer or wine and save that for later, but this time we insisted. The mahiya was strong and rough, and not nearly as refined as boukha. But still, it was a nice break from the araq we’d been swimming in all month. We’d finished a bottle before our main course arrived and because our waiter was somewhere in the kitchen at the moment, I went up to the bar to order it. I should say that we’d noticed the bartender almost from when we walked in the door. He was a largish, bald fellow, maybe 70 or so, though he was trying hard to appear much younger. He’d been looking at us the entire time, and it was slightly creepy. We also noticed that he accosted our waiter often and seemed to be urging him to say something to us, or to translate between us. In short, from how he was looking at us, we knew that he felt he had something to say to us. He was also apparently the DJ for the restaurant’s sound system. At some point, he changed the music from flamenco riffs to Ofra Haza and then some other people we didn’t recognize. Somehow, we knew that he was selecting the music to impress us or at least to communicate something to us. When we ran out of drink and when we realized it might take a while for our waiter to reappear, we picked straws to see who would go up to the bartender and order. I lost.

If you don’t know what the interior of a Moroccan restaurant looks like, I should add some more detail. Imagine faux-stucco walls, their slapped-on texture painted with glossy hues of scarlet. Imagine the walls curving here and there in a deliberate attempt to give you the misimpression that you are not actually in the rectangular box of a strip-mall shop, but rather in an ancient Moorish redoubt whose adobe contours were an organic compromise between land and architecture. Imagine thick wool and cotton carpets and velvet drapes hanging here and there. Now, imagine how all this would look like in broad daylight, and then you can begin to understand why these Moroccan restaurants never have a single window, and why their lighting—the delightfully gaudy brass lanterns strung here and there—is always kept to a minimum. Thus, even though the restaurant was still largely empty, walking to the bar was somewhat of an ordeal. My eyes never saw half of the table edges or puff seats I stumbled over.

The bartender was busying himself washing glasses when I arrived. I waited for a moment, then asked in my rudimentary Hebrew. I did not expect his answer, which he delivered in perfect Egyptian, “Afandim?” Looking at our next bottle that was already in his hands, I knew that he knew what I was going to ask for. Still, I was going to have to converse with him if I wanted it. Without my asking, he told me his name, Yiftachel, and that he was born in Alexandria. Had I ever visited the place? He asked me whether I knew the restaurants and cinemas of Sophia Zaghloul St., or the cafes of Attarin, or the fishmongers of Anfushi, or Saber, the famous confectioner of Ibrahimiya. He then began to rhapsodize about the bars of the city, mentioning in particular, The Spitfire, a dive near the old Bourse. It so happened that I did know the bar. It was a place impossibly dedicated to what some might call “the romance” of the British navy, decorated with union jacks, models of old battleships, and many hats donated by generations of visiting British sailors.

“I’ve always wondered how it survived 1956,” I ventured.

“Funny you should say that, because we were there drinking on the very afternoon that Nasser was shot in ’54. It was only a couple blocks away, and the commotion surged throughout the entire district. Considering, you wouldn’t believe how calm the place was on that day. Of course, was not like Egyptians went to The Spitfire, nor in any case would the police go looking for Muslim Brothers in bars. Though they could have arrested half of us on other charges on any given day! The Spitfire was never respectable, but at the same time, it wasn’t truly rundown. It was right there in the middle, a place you weren’t embarrassed to be seen coming out of, but also a place where the lack of women clientele was not exactly due to accident. We went there when we ran out of money because there was an old French pederast who would come trawling through that bar looking for, as he put it, ‘fresh bori.’ He’d buy any of us whatever we wanted to drink. We were never in danger of being caught in his nets, because by that time of night when he began seek recompense, he’d be too drunk to remember which of us owed him what!

“That night, we sat there in the bar with the radio on, tuned to the Arabic station for the first time ever. I remember the Maltese barman translating everything into Greek for his boss whose face grew whiter and whiter as the night dragged on. The Frenchman paid for our drinks, but I remember, none of us got tipsy even though we drank quite a bit. The shock of the event was just beginning to penetrate that dingy place, like a spotlight shining through the door, showing all the trash and dirt and cockroaches scampering in the corners. That was the moment that the fact of the Revolution finally made its impact on us all, I think. I went home and found my father waiting up for me. Our entire family talked about leaving every night after that, even though it took another five years before we sold what we could and left for good. When was the last time you were in Alexandria?”

By this time, my friends were signaling to me to deliver the bottle. To extricate myself, I invited Mr. Iskanderi to join us when he had a free moment. He said he’d come over when we were finished eating. Our main courses arrived and we devoured them, not so much because they were as good as the recommendations had said they would be, but because we’d already waited more than ninety minutes and were now very hungry. Our Yemeni waiter cleared the table and poured our tiny cups of weak mint tea, again with an absurd flourish found only in Moroccan restaurants. Hani made a joke about how the froth in our cups was probably hot piss, “with tons of sugar so you’d never know.”

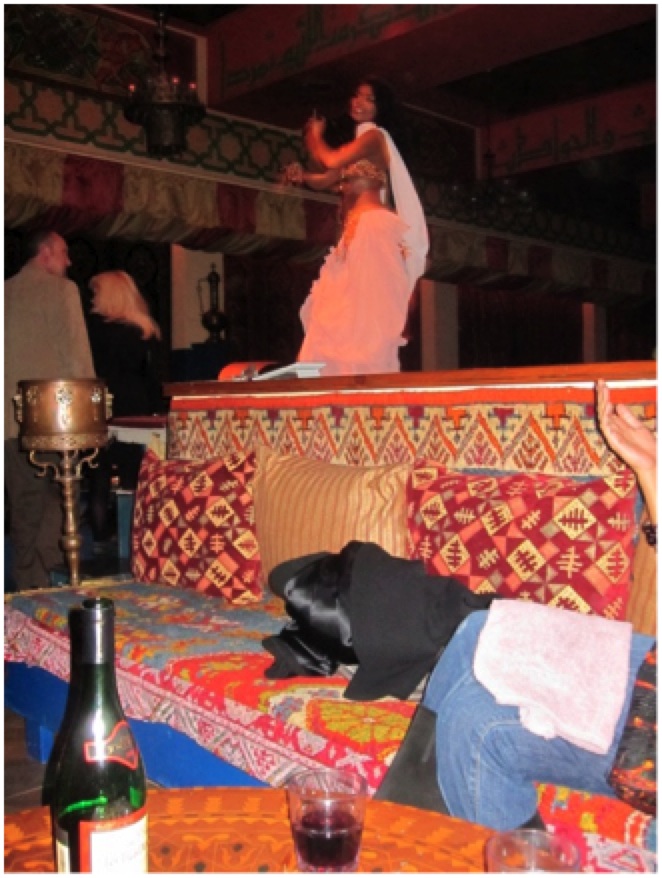

We noticed that the restaurant was now about full, though it was clear that most of the patrons did not come there to eat. Our bartender was busy delivering bottles and glasses of clear liquid to small groups of men, most of whom looked like they were his cousins. Suddenly, a spotlight appeared from the low acoustic ceiling, illuminating the dance floor next to us. The glare from the floor was as unbearable as the bare light itself, and we had to shield our eyes just to see each other. The rest of the restaurant seemed to disappear in a shadow.

Our guess about the entertainment was well-founded, because immediately we began to the hear the rhythms of a well-beaten belly-dance number, and out from behind the curtains popped a lithe woman, wearing scarves and bandanas and coins and bangles. Her dark face was neither beautiful nor unattractive. Neither the forced smile, nor the swath of crimson lipstick could overwrite the scowl permanently etched onto her mouth. We cringed whenever she approached and did backbends over our mint tea. Twice she dragged her hair backwards and upside down through our plates of baklava. Still, we had to admit that she was a fine dancer, and soon we were clapping loudly along with the rest of the clientele, and more than once, stuffed money into her sequined brassiere.

At some point the racket ended, and we motioned to get our bill. I’d already forgotten the invitation I’d extended by the time to Mr. Iskanderi arrived at our table, holding a third bottle of mahiya in hand. It was late, and when he appeared most of us were already psychologically out the door, into our car, and on our way home. Unfazed by our visible mood, this man sat himself down, and began to pour us shots we had no business drinking. Out of politeness, each of us took a sip. Soon, however, he had us in the grip of his conversation, though I don’t know what in fact he was saying, only that he spoke with a rough witty confidence that reminded me of Farid Shawqi. When he guessed that some of us were aficionados of poetry, he suddenly—without introduction of provocation—began to recite lines. At first, it seemed that he had selected them at random. It was all cliché, though we were so stunned we didn’t fully realize that until later. He bemoaned the loss of abodes as if he were a Bedouin, and pined after unnamed beloveds as if he were still a youth. Then, he turned to look at me, and asked if I were a writer. When I hazarded a yes, he shouted, “You think you’re a poet, huh?” and launched into a recitation and I immediately realized that his performance was far from improvised:

السيف اصدق انباء من الكتب في حده الحد بين الجد واللعب

بيض الصفائح لا سود الصحائف في متونهن جلا ء الشك والريب

His pronunciation was perfect and his delivery eloquent, as if he had composed these lines while speaking to me right here and now. I sat in silence, wondering how he had intuited my own struggle during this last month. I couldn’t help but consider the message of the lines in my mind, and sat in heavy contemplation. When I rejoined the discussion, Iskanderi had directed his recitation toward Hani, asking him if we had remained his true friends even after what he had done. He then punctuated his question with a line we all knew well, though in his mouth, its meaning now seemed strange and severe:

هُـمُ الأَهْلُ لا مُسْتَودَعُ السِّـرِّ ذَائِـعٌ لَدَيْهِمْ وَلاَ الجَانِي بِمَا جَرَّ يُخْـذَلُ

I don’t know what Hani was thinking, but something the man had said struck him to the core. He remained quieted and aloof, as did I. Meanwhile, the bartender, went around our group one by one, delivering his lines of poetry like salt on wounds. To Nidal he recited:

لا أنتِ أنتِ ولا الديارُ ديارُ خفَّ الهوى وتولتِ الأوطارُ

To Khalil he quoted:

ألا فاسقني خمرا، وقل لي هي الخمر ولا تسقني سرا إذا أمكن الجهر

فما العيش إلا سكرة بعد سكرة فإن طال هذا عنده قصر الدهر

Each of his lines were carefully chosen barbs. Each hit its target, though I cannot say how. As he went on, we fell victims one by one into all of us sat in a pensive silence.

I don’t know who it was who ventured to ask him to recite some of the moderns to lighten things up, but as soon as we saw his reluctance to comply with the request, we all began to repeat it. And when we saw how it broke the gloomy spell he had cast over us, we went on asking, each time more and more loudly, “Something from the Iraqis! The Egyptians! The Lebanese!” By the time we were asking for poets who were still living, the man’s anger was undeniably visible—as if what we were asking was unfair, as if we were not just being ingrates, but now were insulting him. He began to curse us and, clutching the bottle he’d brought with him, declared that people like us did not belong there. He told us to pay and leave immediately. By now, we had fully sobered up and were conscious of how out of control things had gotten. Many of the other patrons who’d been eavesdropping on the man’s performance were now chiming in on his behalf. Our waiter came over, and switching our language back to English (which he said, “would be safer”), thanked us for coming and hoped we would come again. We couldn’t have left the place more quickly, and even then had to endure the bartender demanding a larger tip. We ran to the car and drove out of the parking lot. Looking back, I saw our waiter leaning on the outside of the front door as if holding back a storm. He looked relaxed as he smoked his cigarette and waved pleasantly at us as if nothing extraordinary had happened.