At that point, I was alone, and so I began to walk back to Tahrir. Someone saw me tweeting and came to me. He asked me my name. So I said, “Hani Sobhi.” He then grabbed my wrists to see if I had a cross tattoo. And when he did not find one, he asked for my full name. I said, “Hani Sobhi Bushra.” He asked me if I was a Muslim or a Christian, and I said I was a Christian.

Hani Bushra’s Facebook Testimony, 8:54 am, 9 October 2011

It was Sunday night, the 9th of October, when a peaceful group of Christian Egyptians marched southwards from Shubra Roundabout in northeastern Cairo to Maspero near downtown Tahrir Square. The reason for the march was a simple quest: to “make our voices heard” in front of the state-owned radio and television building, Maspero, in light of a state of denial of Christians’ legislative rights to practice their rituals. This state of denial has been simmering for years. A simple demand to reverse it and protect the rights of many citizens, unfortunately, turned out bloody that night.

What remains of that night is a cover-up of a vicious scene that included an armored vehicle running over citizens ruthlessly killing twenty-seven Egyptians, twenty-six of whom were Christians. The scene itself was stunning, but what lies behind it is an even more striking, insidious story of diseases deeply entrenched in the Egyptian polity that were maliciously played out to ignite sectarian sentiments within and across social divides—and thereby to spoil the serenity of the 25 January Revolution.

Egyptian Christians clash with soldiers and riot police in Cairo during a protest against an

attack on a church in southern Egypt on October 9, 2011. [Photo: Reuters]

That night, I was asked by thugs hailing from near the Foreign Ministry in Bulaq Abul-Ela three questions. Each was so revealing of the threats Egyptians are facing as part of the counter-revolution’s schemata to divide and rule: “Are you a Muslim or a Christian? Are you an Egyptian or a foreigner? Are you one of those Tahrir folks or are you with us?!”

I was perceived to be a Christian for defending the civil rights of Christians, and thus was beaten that night. I was portrayed as a foreigner for having an advanced cell phone, which appealed to a rumor-making thug who perceived me to be a “spying machine” who merited a beating. Most symbolically, I was perceived to be one of those men beto’3 el-Tahrir (of Tahrir Square), as if was part of a contagious group who had become Egyptian lunatics.

The Maspero Massacre and its aftermath constitute a violent exercise of power led by state apparatuses against minorities and free citizens in a “temporary phase” ironically dubbed the “transition towards democracy.” And this “temporary phase” will (sarcastically) take only two years! And it is a democratic “transition”; cannot you see? There are “no emergency laws” and “no military courts for civilians”; and there is “no one killed under an armored vehicle.” Such tales are “our” imagination, made up by those men beto3 el-Tahrir. Even if us Tahrir “guys” seem delusional, the reality no one can alter is that a crime was committed in the name of putting the streets in order—a crime that even Mubarak in his most oppressive moments dared not to ever commit.

Three distinct counter-revolutionary elements were manufactured as the Maspero state crime transpired—an abuse of state power, fabricated media propaganda, and a premeditated exploitation of religion. These deliberate strategies were orchestrated as part of a larger Security Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) scheme aimed at dividing Egyptian society and crushing the January 25 Revolution. I explore each of these elements of fissure through eye-witness accounts (sworn online testimony) and an analysis of SCAF’s behavioral patterns as exemplified by SCAF member and General Hassan El Roweiny boasting about the power of rumors in his televised phone interview with Dina Abdel Rahman on the “privately-owned” channel, Dream TV, for which Ms. Dina was sacked. The current “military strategy” aims to spread rumors to incite “the masses” with sectarian and divisive passions. To what degree fact can be separated from powerful rumors as events played out in Maspero on that bloody Sunday evening is likely not only left to “our lunatic imagination.”

My essay’s analysis begins with a description of how the abuse of power was enabled by Egyptian Armed Forces, whether Central Security Forces (CSF) officers, soldiers or hired thugs. Second, I explore the role of state-owned media as propaganda in disseminating fear and rumors. Third, I discuss how the exploitation of religion became a deadly instrument to exclude and damage those deemed to be “the other.”

The Exercise of State Power and Thuggery Violence

The question of who started the Maspero gunfire on 9 October 2011 remains a key question in this case. While some theories allude to the presence of a third party, whose members enflamed the sedition, all eye witnesses agree that an excessive use of violence by military troops was evident.

An account by Rabie Fahmy, who happened to be there to buy batteries at a nearby Radio Shack, includes a graphic photograph of a murdered citizen. Fahmy states: “Before the march reached Maspero, the army fired shots into the air to disperse protestors...They then opened the way for armored vehicles to penetrate deep into the crowd…Gunfire shots were dense and provocative, stimulating violence then fear.”

In his account, Hussein Bakr ponders: “The military attack was offensive, extremely violent, and unjustifiable. Army soldiers were acting aggressively and brutally, inconveniently awkward to the protestors who were armless...I did not see any firearms or even white weapons among the protestors.” Bakr goes on to explain how a row of military police officers standing behind soldiers were cheering them on using provocative chants—“Those are the people who want to burn the country; those have killed your brother soldiers and colleagues. We are your brothers; we are with you!”—after which soldiers would viciously attack protestors.

While soldiers kept repeating these slogans, some of them fell down. Many eye witness accounts, including that of political activist Nawara Negm, confirm that there was not a single corpse of a killed soldier. False news to the contrary from officers might have electrified soldiers to act more brutally as they learned, incorrectly, about the death of colleagues. Yet later, during a 12 October 2011 press conference, SCAF members refused to officially announce the number of soldiers who “fell” that night. This has left people with mere speculations, confusion, and doubt.

Later updates revealed a circulating online video of a military funeral of a soldier, which perhaps was true. However, what is at stake is an increasing space of mistrust. SCAF’s stagnant position and lack of transparency has increased the gap between it and the people. SCAF’s attitude deprived the dead soldier a popular funeral by the rest of Egyptians and civilian activists who lament each and every Egyptian killed that night, regardless of their religion, gender, race, sexual orientation or profession. Regardless, false information does not justify the brutality of soldiers, but surely does evince the pressure exerted on them, and the hatred this generates. And no one knows what soldiers had on their minds when they drove their armored vehicles into the protesting crowd.

Early that evening of 9 October at 6:26pm, political activist Lobna Darwish wrote on Twitter (then Facebook), “Sons of dogs! Opening fire on a march full of children!”—as two armored vehicles moved insanely into the crowd, running over people to-and-fro. Darwish described the horrific scene further: “The vehicle would chase a group of people trying to run away, go over the street pavement, crush them, then see other people on the other side, so chase them until they too ran them down. It was moving in a zig-zag. Then, two armored vehicles were replaced by another two, each pair doing the same zig-zag chase. It was unbelievable. I was terrified. People were running everywhere... There were two young kids between fourteen and fifteen years of age hiding behind a car. The armored vehicle spotted them and ran over the car, destroying it and running over one of the kids.”

Three armored vehicles disappeared into the night, whereas a fourth suddenly slowed down. People gathered around it, showering it with stones. They stopped it by throwing a broken traffic light that was on fire at that moment. The vehicle caught fire too, and a soldier inside tried to get out. Some people shouted, “Stop the stones! Let him out!” So, protestors stopped until the soldier made it out. Then, they viciously attacked him. “This soldier just killed our brothers, heartlessly running over them!” people cried. On a video circulated on YouTube, a Coptic priest was the one who intervened to protect the soldier, taking blows instead of him. Were it not for this priest, this soldier might have been killed.

Steve Nabil Helmy estimates that the soldier in the armored vehicle that went ablaze ran over at least fifteen people. He saw “people [lift] crushed bodies into the entrances of neighboring buildings as they ran from the horrific scene.” In turn, witness Mohanad Aborehab, who works near Maspero, saw the armored vehicle moving quickly into the crowd too, with neither prior notification nor provocation. He took photos of a man killed on the street after being crushed and of four others lying dead in a nearby building where their mutilitated bodies were rescued.

Another protestor and activist, Mohamed El-Zayatt, asserts that he heard and saw the use of gunfire against protestors before the armored vehicle started crushing people. A protestor right beside Zayatt was shot dead, just before the menacing vehicle appeared, and all ran for their lives. Blood was everywhere. Human organs were dispersed in every corner: a brain here, a spleen there; evidence of despicable, murderous acts. After seeing bloodshed, protestors vengefully hit back by showering a public transportation bus also with stones as it too was set on fire as an ultimate reaction to their helplessness in front of wicked armored vehicles.

In his account, Bishoy Saad proclaims: “I saw two people carrying someone whose lower body was gone. I looked at his face and saw that he was the one chanting in front of me. I was walking next to him when I joined the march until I stopped to get a Pepsi. So, if I had not stopped to get Pepsi, I would have been in his place. I saw several people who had taken in bullets all over their bodies. Their blood drenched the streets.”

Almost in the same time, a police vehicle was set on fire behind the back rows of army and CSF officers. Fahmy confirms the impossibility of protestors being able to reach deep behind where they were: “The police vehicle was deep inside, way behind, out of protesters’ reach in an area between army lines and people who eventually gathered to support the army.”

SCAF, together with some politicians, have assured “us” that soldiers guarding Maspero carried “fake” bullets in their machine guns. This leaves us with a dilemma. Who did the shooting then?

Ahmed Mustafa II, who had been covering a press conference about Bahrain for the Arab Network, came running near the scene of these crimes at Ramsis Hilton, only to find “a 5-cm bullet with a red mark casing on the ground.” Some believe this red mark to be emblematic of “military police,” not “army soldiers.” This remains a speculation. Only a probe and further interrogations can reveal the truth about the bullet’s source. Yet, the testimony of Mohamed El Ziny’s testimony confirms Mustafa’s: “I could hear live ammunition being shot… And I swear to God, I saw bullet casings with red tape on them. When I asked about them, I was told that these belong to the Military Police.”

The above accounts describe the situation looking into Maspero from Ramsis Hilton, but what about the situation from the other side of Maspero: from the 26 July Bridge? Because of their different perspectives, I will share my own account with those of four other eye witnesses to describe the crime scene from another angle.

Mohannad Galal confesses, “At first I thought I was with the revolutionists, then suddenly I discovered I was with the thugs and rioters, because I found some of them encouraging the army to crush demonstrators. And some of them carried kinds of knives which were new to me…Some were saying to others: ‘The right of the soldiers must return!’”

In turn, I saw a group of people dragging a guy on the ground, beating him and saying, “We found a Christian!.” The place was full of CSF officers collaborating with thugs. I saw it with my own eyes; thugs had beaten this man and delivered him to the police who continued torturing him until an ambulance came and took him away. To where? I do not know.

Galal’s video footage of what happened is quite revealing and includes officers in full riot gear.

Inside a garage where neither I nor Galal entered, Ragy El-Kashef “saw a scene with my own eyes that will forever haunt me. There was a woman with a child and her husband. They were carrying a cross and standing in the Maspero parking lot. Suddenly, soldiers attacked and assaulted the three of them, as well as another woman who had a child carrying a cross in her arms too, for absolutely no reason. They had not even uttered a word...They all (thugs along with military and CSF officers) continued assaulting them in every way: slapping, kicking, head butting, and using their batons. I could hear one woman screaming, but I could not do anything about it. I could not even say ‘This is wrong!’”

Clinical pharmacist Khaled El Sherbiny tried to help Christians who took refuge in a garage. With his friend, El Sherbiny succeeded in helping a few escape and in moving some of the injured to Ramsi’s Hilton Hotel, out of harm’s way. He says, “Thugs were smashing cars parked behind Maspero building from the other side. The injuries were serious, most cases resulting from the use of sharp and semi-sharp metals...Suddenly, I heard very loud screams. Thugs had entered the garage.”

If these street and garage scenes were all horrific and barbaric, what comes next is no less shocking. From a different bridge located on the Southern side of Maspero, El Kashef reveals, “I was standing on the October Bridge and saw three soldiers carrying a corpse that they threw into the Nile. A military police officer was standing with them. When I pulled out my camera to take a picture, the soldier yelled, ‘Get that son of a bitch with the camera!’ But I ran away until I reached downtown.”

I have to stop for a moment here. Even in war, moral conduct and international law require “respect” of the enemy and the dead. But that night at Maspero, there was no enemy. Everyone was Egyptian. And above all, we were and are all humans. What on earth would make an officer give such an order: to throw corpses into the Nile?!

They did not even bother to wait for an ambulance to carry the dead to the hospital. They did not have neither the patience, nor the decency or tolerance to accept the presence of “the other” in their midst: dead or alive. Why? Perhaps they recognized that they were in a crime scene of their own making and thus had to eradicate any and all evidence. If that was their motive, then with it comes an affirmation of responsibility for the crime they committed.

The symbolic and material significance of “throwing corpses into the Nile” must not go unquestioned. The psychological vengeance embraced by those who did this throwing is neither something that can go unnoticed nor temporarily pass as a distant memory to be forgotten. This problematic disposal of dead Egyptians requires a transparent and just action: an investigation into the crime and its aftermath.

What followed elsewhere was no less problematic. As the street fight moved from Maspero to Abdel Moneim Riyad, near Tahrir Square, a large group of military soldiers “swept” the area together with “civilians” wearing helmets and armor—in a manner similar to attacks against civilians on 1 August 2011 at the beginning of Ramadan, the holy Muslim month of fasting.

As Shaimaa Yahya witnessed, “Some thugs got over the 6th of October Bridge; others got under. They attacked protestors.” Ahmed Ibrahim’s account clarifies further, “Muslims and Christians were together like one hand…A sheikh was carrying a cross and was lifted up by the demonstrators… People chanted against SCAF and Tantawy…People came from Hilton Street chanting the same slogans. But the battle was between us and thugs who were backed by CSF officers behind them, as we crossed the October Bridge ramp at the side of the square.”

Street fights continued into streets and cafés in downtown Cairo, where some activists got arrested at Boursa Café. Hossam Fawzy recollects: “Army forces are reviving memories of 28 January with the very same roughness, brutality, and disrespect for human rights.” I, myself, saw thugs with swords, knives, and sticks attacking citizens inside Tahrir Square.

Just as a reminder, the call for dignity was a major demand that exploded on 25 January. What happened on 9 October was akin to the same humiliations that authoritarian forces dealt Egyptians before 25 January, and which still continue to this day. The shadows of our martyrs are still covering our clouds: Khaled Said, the martyr of Emergency Law, and El-Sayed Belal, another martyr of violence. And now, witness the annual assault on Egyptian churches that comes every year—as if it were a Mubarak tradition worth maintaining. And as of 9 October, we must add to those murdered the free souls of Maspero: Mina Daniel and every Egyptian who died or was injured that night.

When Media Becomes a Military Weapon

It is perhaps only in Egypt that you find state-owned television calling for people to rescue and save the army from other citizens in such a timely fashion! Welcome to Egypt, nine months after the spark of the revolution!

As he followed events on Twitter and television closely, Ahmed Mounir (who was not present during the Maspero Crime but ran to the Coptic Hospital to donate his blood) wrote: “It was the despicable Egyptian state television that incited strife by broadcasting news of the death of army soldiers and reporting that Christians were killing the army! What is more, it even issued a call to citizens to go out and protect the army from Christians! This was a clear attempt to ignite conflict between Christians and Muslims.”

According to Nawara Negm, security forces and the army disappeared behind the lines of thugs, so-called “honourable citizens” whose moodiness and emotional inconsistencies everyone noticed: “We are not here to attack you; do you think we would attack our brothers? We are here to protect the army. Because three of the army men are dead. The TV said so.”

These provocations made a group of Christians call for people’s “wisdom” on Twitter and for them to “not believe Maspero”, that is the broadcasts coming out of state-owned media. Bichoy Saad tweeted: “I beg all of you, now! Do not believe a word of what is being said on Egyptian television, no matter how respectable or trustworthy the person. Every single inch of this filthy place (Maspero) is controlled by the military. There is not a word that gets said there that is not pre-planned and pre-calculated.”

During the events that I call herein the Maspero Massacre, Rasha Magdy, an anchor of Egyptian state television accused Copts for being responsible for the incidents and for attacking soldiers and killing three of them. Yet, the most ridiculous excuse came afterwards by her boss claiming Ms. Magdy and the broadcasting team had “gotten nervous and might have exaggerated.” Meanwhile, the main news bar continued to notify the public: “Urgent: Three martyrs and hundreds injured among army soldiers and police by gunfire from Coptic protestors in front of the Maspero building” (see the screenshot below)

Snapshot of unchanging Egyptian television byline accusing Copts of

killing army officers at Maspero. [Image source unknown]

Was this “exaggeration” just a symptom of a broadcaster’s nervous breakdown? Magdy later claimed that she receives all her information from the channel’s editor. And since she is not a field journalist, she just delivers what she receives. By providing this explanation, she accused a higher-ranking state employee of creating this deadly rumor between state media employees.

As a scholar, I cannot help but draw parallels between the rumor that ran among state media employees and the rumor that ran between army soldiers, who also follow orders and do not investigate their meaning. Amidst all this fuss and anger, SCAF’s press conference on 12 October 2011 nevertheless thanked Egyptian television for its “credible and responsible” footage!

A Machiavellian rule of state domination is to control any and all opposition as “the other.” If state-owned media had been controlled, what about other numerous satellite channels? Well this time, for the Maspero situation, a more oppressive strategy was required beyond just breaking Al Jazeera. For superior control, the state allowed “the other” opposition a sense of “freedom” but with conditions. Be democratic but do not cross the fine line!

Media control is still at work in Egypt, and the opposition media must be bounded, the usual hegemonic strategy of authoritarian regimes. Yosri Fouda’s case is a relevant example of this kind of strategy. Fouda is a free-speech anchor who was forced to make compromises if he decided to question SCAF’s performance with the novelist and critic Alaa Aswany. Fouda understood the depth and danger of tainted approaches to “illusive democracy” and accordingly halted one of the best talk shows in Egypt “Akher Kalam” (Last Words) on 21 October 2011.

On 9 October, Military Police acted as if they had a green-light to do anything regarding non-state media. They terrified news agencies and privately-owned satellite channels who were reporting on Maspero events, setting an example for the rest with the few. Soldiers broke into two channels’ apartments, those of Al Hurra (The Free) channel and Channel 25. They wielded their weapons, terrifying everyone. They searched for hiding protestors, materials, and who knows what else?

A Channel 25 editor-in-chief, Mahmoud Gamaleldin, blogged that he heard live artillery coming from the Egyptian Radio and Television Building at Maspero. He also saw CSF battalions clashing with protestors and watched “other civilians” burning parked cars by the corniche with Molotov cocktails. He did not get it at the time, he wrote on Twitter: “I am seeing cars being smashed and burnt intentionally and do not know who is beating who.”

A YouTube video shown on Channel 25 revealed the voice of a woman yelling: “I am pregnant! I am pregnant!” According to Gamaleldin, these calls were those of the anchor who was live on air, crying and pleading with eight CSF officers under the command of a military soldier who barged into her working studio showing their weapons. Gamaleldin claims these forces had beaten two channel employees during their “inspection.” These forces were accompanied by a group of civilians holding sticks and stones, whose very presence was awkward. After inspecting the place and the rooftop of the apartment building, a CSF officer apparently told the lead military soldier that this satellite channel has nothing to do with Maspero, and he should put down his weapon. The military soldier scolded him, hit him in the chest, and told him, “Malaksh hokm ‘alaya ya basha” (You have no command over me sire), commanding the remaining CSF troops to follow him. On their way down, they broke the elevator’s glass and glass windows of the channel. This revealed the drummed-up anger and fact that even a higher ranking CSF officer had no command over his forces, whom were led by a soldier.

The media was influential in amplifying a state of confusion but it would not have been so were it not for pre-existing sentiments of hatred that found a fertile ground to nourish and grow that night against Christians. The fabricated information broadcasted gave a good medium for sick minds, backed by state forces to act violently against Christians and “Tahrir” protestors. There were two parallel objectives put into play. First, a rooted sectarianism that the state had implanted since late 1970s by former president Sadat, to ease governance using the philosophy of divide, dominate, and conquer. The second was to taint all those who defend Christian civil rights and mark them as beto’3 elTahrir, even if they were Muslims deemed not good enough given their lack of desire for an Egypt “Islamia Islamia”: a doubly Islamic State.

The Induction of Religious Divides

During the eighteen days of revolution, no one asked the question: Enta mulsim wala messehy? (Are you a Muslim or Christian?) On the contrary, glorious scenes of the unity between Muslims securely praying opposite Christians and priests was the norm. These were true moments of coexistence or what I would call “pluralist democracy,” as Chantal Mouffe would describe. [1] Pluralist democracy is the domain that lies between the power of the majority and the true values of democracy. Many times, the power of the majority becomes antagonistic to the rest despite the fact that social objectivity cannot identify itself except through differences.

It is through the presence of “the other” that one defines one’s own identity; this is what is known as “the constitutive-outside.” The outside becomes a major constituent in producing the inside, in which the inside itself becomes a purely contingent and reversible arrangement. Both produce and reproduce each other and they only become antagonistic when their relationship is manipulated politically as Carl Schmitt points out through religion, morality, ethnicity, etc.—as “friend-enemy” relationships.

According to Mouffe, it is only when we acknowledge this dimension of “the political” and understand that “politics” consists in domesticating hostility and in trying to defuse the potential antagonism that exists in human relations, that we can pose the fundamental question for democratic politics. This question is not how to arrive at a rational consensus reached without exclusion, or in other words how to establish an “us” which would not have a corresponding “them.” This is impossible because there cannot exist an “us” without a “them.” What is at stake is how to establish this “us-them” discrimination in a way that is compatible with pluralist democracy.

It was “the political” dimension of antagonism from “the other” that dissolved Muslim-Christan relationship in Midan Tahrir (Tahrir Square). Maybe this explains how this “mode of surviving through the other” dissolved after nine months— ever so quickly in one evening? Was the “Maspero incident” a purely Christian-government conflict or was this sectarian divide the state deliberately wanted to convince the rest of Egyptian society of? Was it a minority issue or not? Or was the Maspero March a protest for human rights led by Egyptians who were mostly, but not only, Christians? This latter question is what I hope to shed light upon here.

It is worth mentioning that on 4 October, a group of Christians held a small demonstration in front of Maspero to protest against the burning of part of Marinab Church in Aswan, a governorate in Upper Egypt. This “other” incident occurred under the supervision of the Governor, who explained that the building violated city building codes. The Marinab burning caused yet another violation against the right of Egyptians to practice religious rituals. And the small protest and sit-in faced soldiers’ aggression as shown in this YouTube video.

The Maspero March, in turn, reflected this more general human rights cause for freedom of practicing rituals. The march was mostly led by Christians but Muslims played a role in the march and struggle as well. If the state attempted to divide Christians from Muslims, in the future it will continue dividing Muslims between themselves, Christians between themselves, then revolutionaries and activists among themselves, politicians between themselves, and so on and so forth. So goes the Egyptian state’s game of divide and rule.

According to Bichoy Saad, the Maspero March started in Shubra packed with both Muslims and Christians. Muslim protestors were mostly political and human rights activists who believed in the freedom to practice your community’s rituals and religion— usually the same figures who appear in every citizenship cause, including those known as the “Tahrir fellows” or those beto3 elTahrir.

Elziny, who missed the start of the demonstration, reached Sabteya later after the protest has passed by. His exposé reveals entrenched sectarian residues embedded in Egyptian society. He says when “I arrived at Sabteya...I found a kiosk on fire and a wrecked truck. I asked different people about what happened. I asked an old man...He told me that Christians are the ones who started this fire and broke the truck. He also said that Sabteya people had beaten them up because they were chanting against the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafis. The old man also saw that they had shot guns and were big in number, around thirty to forty thousand…I [later] asked a Christian about what happened, he said that Sabteya people were the ones who blocked “their” way and beat them up, and someone threw a Molotov cocktail over the kiosk from a car and then drove off.” The punch lines, one after the other, evince a society divided upon itself. Their tales are full of generalizations and exaggerations ready to accuse “the other,” regardless of fine-grain details of the truth.

The Sabteya incident all happened before the media’s devilish intervention. It seems that before the arrival of the march there, a great sense of hostility began to surface on the horizon with quick references to religious groups including “the Salafis” and Muslim Brotherhood, even though neither had anything to do with the situation. But in a society as any other, full of rumors and hearsay, “news” travelled like the speed of light. Several accounts revealed a small battle with stones near the tunnel of Ahmed Hamdy as the protestors passed it along, but the original message did not last for long. Saad recalls, “Throughout the march, we insisted on peacefulness, and the Father warned us several times against provocations or creating friction that leads to violence.”

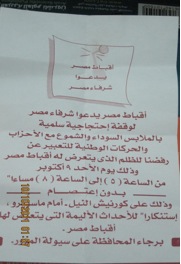

Wafaa Mahmoud posted a “Copts` Statement” (below) that was distributed that day among the protestors. Egypt’s Copts called for a peaceful stand, confirming Saad’s recollection.

Copts’ Statement [Image by Wafaa Mahmoud]

Her online post affirms, “The Copts of Egypt were calling for a peaceful stand in black with candles for the injustice that Copts are facing without sit-in. They were dressed in black to symbolize injustice and held candles lit to symbolize their hope for justice. The protestors had no intention to ‘sit-in’ in front of Maspero or hinder the normal flow of life in the streets in a clear statement. They just came to make a stand then leave without causing disturbances. That is why they pleaded the protestors: ‘Please maintain the flow of traffic!’” This plea reflected the march’s initial intention that dramatically ended instead with the regime’s austere accusation of protestors for doing far more: possessing weapons and attacking soldiers.

In each and every case, rumors of violence had arrived to Maspero well before the demonstration itself arrived, raising the heat and presuming hostility. I came to Maspero from 26 July Bridge, where people were chanting: “El-akbat fein? Elmoslemeen ahom.” (Where are the Copts? Muslims are here). I did not understand the situation at first, but later realized that I was standing among the people of Bulaq Abul-Ela who had been called to “save” army soldiers from Copts.

Hossam Fawzy “saw a passer-by cursing Pope Shenouda.” He goes on to say, “I heard a military soldier asking a taxi driver to run over a group of standing Christians. When I intervened, I was attacked by two thugs, one using stones and the other a wooden stick...I then saw narrow-minded Muslims totally acting against their faith. And when I got involved in this conversation, I was yet again faced with the same violent reaction.”

Manar Ammar, another survivor of the tragic crimes and misinformation that night, writes in her account the following: “Others told me that there were rumors circulating that Christians were burning the Quran, and Muslims had come out to defend their religion. There were calls to ‘Hold your head up high; you are a Muslim!’ Similar sectarian cheers were called in response, like ‘Hold your head high; you are a Copt!’” What hurt us listening to these calls most was that people seemingly forgot that we—all of us—are all Egyptians.

During these intense back-and-forth religious counter-chants, Nawara Negm observed that “a central security soldier took one man’s hands and looked at it to find a cross, so he pushed him towards the ‘honorable citizens’ shouting ‘Christian!’. Yet these ‘honorable citizens’ dragged him to the beginning of Sahel Al-Ghilal Street and beat him brutally... A friend of mine and I went to rescue him, and my friend yelled, ‘Is this the prophet’s commandment upon your brothers?’ An ‘honorable citizen’ punched her in the eye.”

Given such hostility, Negm and her friend went to the Coptic Hospital to help the injured. She recalls, “When our cab was on its way, it was confronted by demonstrating ‘honorable citizens’ armed with sticks and Molotov cocktails, so my friend had to stick her head out of the window so the ‘honorables’ could see that she was wearing a veil…and was not Christian.” Negm continues, “I went into the morgue, and saw the martyr’s corpses. I contemplated their bright smiling faces (I swear to God they were smiling). Among them I found one whose brains had come out of his head as a result of being run over by an armed vehicle. Then, I went out to find Christian and veiled Muslim women mourning their sons. And finally, army tanks came by announcing: ‘We have come to protect you!’ On top of each tank was a bearded civilian carrying the Quran.”

Since she was wearing a veil, Shaima Yehia was asked by a Christian family who had been part of the protest to escort them. She felt troubled that they felt this need to be shielded from Muslims by a Muslim. El Sherbiny, the clinical pharmacist mentioned earlier, went back to Abdel Munim Riad Square to receive medical supplies from donors. Yet another group marched by, demonstrating and chanting “Islamic, Islamic!” But he notes, “Frankly, they did not look ‘Islamic’ at all.”

Negm clarifies further: “Among the ‘honorable citizens’ were people who work for the Ministry of Interior. Their faces are recognizable from the incident at Abassiya.” On 23 July, the day the Egyptian Army celebrates overthrowing the Farouk I monarchy in 1952, a protest march from Tahrir to the Ministry of Defense in Abassiya was held to express anger with SCAF. The Egyptian Army asked residents and other civilians to engage and halt protestors instead of them doing this task, in order to prevent any possible clash or diversion to ruin the Army’s celebrations.

On 9 October, there was a general sense of confusion. People wondered where are the so-called armed Christians? One protestor said, “I came out to protect the army because they said that Christians were shooting them. I arrived to find the army shooting everyone; Muslims attacking one another; Christians attacking one another; and no one knew anything. So, what was the real deal?”

This manufactured “state of uncertainty” was created tactfully by SCAF to reproduce a quasi-controlled environment that prevailed before, during Mubarak’s regime and pre-January 25 when no one really understood anything about what was really going on. Egypt is in a condition of diminishing transparency. Accusations are on the rise; social categories divide us ever more. And the innocents are the ones who pay the price.

Conclusion: Maspero’s Significance and the Revolutionary Road

Was Maspero a series of crimes that attempted to suppress demands for Christian rights to practice their faith or an attempt to coerce the basic, broader demands of the 25 January Revolution: 3eysh, 7oreyyah, wa karamah insaneyah (bread, freedom, and human dignity)? Or is Maspero to be understood as a double entendre: a military state crime doubly coded as a threatening message to suppress both Egypt’s Christian and revolutionary communities regardless of faith?

Was our experience of coexistence with and among “others” in close quarters at Tahrir Square for eighteen days intentionally imploded by the Maspero Massacre? Had we just been living an exceptional temporary utopia that will haunt us forever, as our memories of the good old days are jolted back to reality?

No. It was not an illusion. Remember: 2e7na beto3 elTahrir (we are the Tahrir fellows) who surmounted barriers of discrimination based on class, gender, race and profession—divisions that the authoritarian regime manufactured to divide Egyptian society for decades. It would be romantic if one thought these barriers could be so easily dissolved. On the contrary, we should deal with them on basis of our differences and come together under the umbrella of “citizenship.” Maybe what the Tahrir fellows constructed was a temporary condition that needed nurturing to become the new status quo. This is the struggle we have to fight now: a struggle to create a different “third space” as Stuart Hall and Homi Bhabha would describe—a space that lies outside the realm of social divisions and culturally-constructed binaries.

I do not mean to negate the realities of difference and diversity. The politics of identity manifests itself most clearly during moments of crisis and conflict. Maybe it is time to find an understanding of Egypt’s “identity question” by conserving a unity within diversity, instead of attempting to find only common ground and similarities between us. We can claim that “Muslims and Christians are brothers and sisters.” But this is not reality…yet. We should instead critically accept our differences and not subvert them. This is a mental and social exercise for the “constitutive outside.” It would be better to start first with our differences; we should respect and guarantee each other’s peaceful survival. These fluid formations or “political constructions” of difference are not fixed and have been culturally developed to dominate and control. And yet these social divides have been aggravated for decades. It would be naive to think we can just dismantle them without “justice” and the “rule of law.” This is a call to “pluralist democracy.”

Our fear of “the other,” our culture of exclusions, policies of social marginalization, and sectarian segregation remain key quandaries in Egypt, as in the rest of the Middle East and the world. Demonstrations worldwide attest to these quandries. Whether in Libya, Rome or Wall Street, we are forced to ask: "Who is the other?" in every State and “What are the roots and contingencies of dealing with the other?” We need to address these questions through cultural and educational actions that articulate with our schooling and university systems, as well as family and communal units.

In Egypt, the relationship between regimes and minorities is one way street, a sort of downward spiraling relationship based on a “benevolence of generosity” rather than a relationship founded on citizenship rights and duties. Unfortunately, as it stands, it remains a top-down approach. We should reframe this relationship into an indispensable bottom-up dialectical one. And this is the goal for our ongoing revolution.

I want to emphasize this notion of “benevolence of generosity” that accompanies SCAF discourse to the Egyptian people. Probably the most explicit statement that reflects this view, whereby “the other” becomes “us” is one made by Lieutenant Kato, who told the anchor Dina Abdel Rahman of Dream TV, “Elkowat elmosalahah bet3allem elnas KG1 men eldemocrateyah” (The military forces are teaching people the first steps of democracy, or KG1). He goes on to say SCAF is “giving a big opportunity for people to express their opinions, and they should learn how to use this opportunity.” Interestingly enough, Dina Abdel Rahman was sacked right after this episode for crossing the lines of freedom with Lieutenant Kato. Welcome to the government school for “KG1 democracy”!

Amid this environment of counter-revolutionary attacks, our basic revolutionary call still stands: 3eish, 7oreyah, karamah insaneyah. The Maspero Massacre, including what transpired during and after the various crimes involved, has exposed many embedded fissures, deeply entrenched and tearing apart our Egyptian society. Some were fostered by the previous Mubarak regime. And some are being fostered during this political transition. It is time to openly confront them!

To summarize, three kinds of thuggery were manifested that bloody Sunday night at Maspero: elbaltagah al-mo’tadah (conventional thuggery); elbaltagah al-ma’loomateyah (information thuggery) and elbaltagah al-deeneyah (religious thuggery).These three types of thuggery strike directly at the heart of national economics and security, not the everyday strikes for social justice, stigmatized as “mozaharat fe’aweyah” (class demonstrations). Those who talk about the 3agalet el-entag (wheels of production) are framing the issue with the wrong questions in the wrong manner. How can you blame strikes for economic deterioration while you lack a just order for the distribution of resources? People tend to ask the wrong questions, such as Negeeb felous menein? (Where do we bring money [to give our employees])? But those who ask this question lack an understanding of the “generation of capital”: the basic rules of economics. We do not make money, money is circulated. And in Egypt, as in the rest of the world, there is an uneven distribution of resources, i.e. an uneven circulation of capital.

How can you expect estekrar (stability) amid gheyab amny (an absence of security)? People tend to use the wrong terms, talking of infilat amny (loose security), while we are suffering from an “absence of security.”

Amid all these false framings and identification of key issues, romantics take a leap of faith and believe that parliamentary elections will solve our political disjuncture. What is striking is that the 2012 parliament will have less powers than the 2010 parliament under Mubarak. In other words, according to SCAF’s Constitutive Declaration of 23 March 2011, parliament members will have no power to legislate rules, no authority to form government, no power to bring it down, interrogate it or form specialized committees as before. So, after our so-called “revolution,” we are electing a parliament weaker than that under Mubarak. And so, we place even more power upon the ruler, rather than the ruled!

SCAF wants us to remiss, after the revolution: to yearn for Mubarak’s era. But we have to remain focused. We are not in a post-revolutionary phase yet. We are still living in revolutionary times, in the struggle. To be more precise, we are in a phase of SCAF’s rule as a continuum from the rule of Mubarak, who was the one who put them in control in the first place.

So what next? To see the big picture and have a clear perspective, we have to analyze the push-and-pull factors and forces of power causing our current condition. SCAF’s own dilemma is that it is wearing two crowns simultaneously, each representing different logistics of operation. On the one hand, SCAF is the military protector of the Egyptian state, while on the other hand, SCAF is practicing transitional politics in a centralized manner: assigning ministers, legislating rules, approving parties, etc.

Both impulses—the military and the political—have two different institutional mindsets that together cannot be one and the same. One is operated through defensive and offensive mechanisms through a hierarchical set of ranked officers, while the other is operated as a “social contract” between the state and its citizens without a rigid hierarchy. The first one is military in its nature and entails no democracy, while the other is civilian in nature, signaling the hope of becoming democratic. One entails a “school of KG1 democracy,” while the other beckons an end to patriarchal democracy. Both are different faces of the same coin and appear to be talking two different languages. Maybe this is why we cannot understand how SCAF can arrest a few citizens for its version of “Maspero criminal activity,” while neither interrogating itself for potential wrongdoing as a political-military body nor the Minister of Media nor for matter any of the police officers who allowed or encouraged thugs and CSF officers to intervene. Or to put it more precisely, how can one be the judge of a crime one is accused of committing or of bearing at least some responsibility?

Subcomandante Marcos once said, "Ideas are like weapons." I would say, while weapons are instantaneous in effect, ideas are more everlasting. They spread, motivate, and control, leading to those that hear or act upon them to have unpredictable expectations. Watch out! Because this is an uprising of the people. It signals a rise of megacities that are stronger than weapons. Remember John F. Kennedy’s warning: "Those who make peaceful revolution impossible, will make violent revolution inevitable."

Power, media, and religion have become the key elements which helped produce Maspero crimes, and the same three modes of action are what revolutionaries need to focus upon to retrieve the January 25 Revolution. If “power” to the military has been “artillery weapons”, our “power” comes from “the masses” and a deep belief in our cause for freedom and citizenship rights. If “media” to them is state-owned radio and television as conventional tools of broadcasting, our “media” is virtually online and becoming ever more mobile and decentralized. If during Mubarak’s reign they were motivating Facebook groups like Kolena Khaled Said (We are all Khaled Said) or the April 6 Movement, today we have ever more Facebook groups linking more people and growing every day. Today, after the Maspero Massacre, we counter instead with Kolena Mina Daniel (We are all Mina Daniel), as well our own discourse for thwaret elghadab elthanya (the second revolution of anger), ellegan elsha’beya leldefa ‘an althawrah almesreiyah (popular committees for defending the Egyptian Revolution), and elgabha elkawmeyah lel’adalah wa eldemocrateyah (the national frontier for justice and democracy), among others.

As of today, there are multi-nucleated centers of gravity, together with labor movements and socialist groups. SCAF with its intelligence and CSF virtual teams of surveillance will fail to penetrate, because their officers’ mindsets are geared to compromise, violence, and centralized battles. If their “religion” was used to divide us and create hostility, our “religion” is oriented towards building “unity among the diverse.” If they succeeded in distancing ordinary people from the Egyptian Revolution and make some people hate “Tahrir” as its central symbolic space, new street tactics will develop with night marches scattered around our megacities.

The revolutionary pulse is growing in new forms of grassroots action, including those of legan sha’biya (popular committees), everyday struggles, and confrontations with municipal authorities and Governorates on issues like garbage collection and urban governance. The Egyptian Revolution is becoming more and more dynamic, decentralized, and multinucleated. It is growing by way of everyday actions, strikes, and even football cheer groups for Ahly or Zamalek soccer teams.

The control of persons or groups will become ever more difficult as SCAF struggles to find representatives to negotiate or compromise with or that can be tamed and appeased. Since SCAF now wears two gowns, or two crowns if you will—a military one and a political one—it should know that it cannot rule “politically” with the same “military” mindset of hierarchy and pedantism. It is time for SCAF to “listen” and be “political” in a civilian democratic sense, because it is already late, and there is no turning back.

A crime has been committed, and the martyrs of Maspero—Christians and Muslims alike—did not die. They were murdered! It is impossible to undo this history.

As the Chinese saying goes, “Half-revolutions are the tombs of their nations.” That is why there is no turning back. And until our revolution meets its end, we will continue to call for eish, horeya, ‘adalah egtema’eyah! “Bread, Freedom, and Social Justice!” This is what the Egyptian people demand. I salute the Egyptian martyrs who fell down since the beginning of the revolution, during that night, and those to follow next. May You Rest in Peace!

[1] Mouffe, Chantal. “Post-Marxism: Democracy and Identity” Environmental and Planning D: Society and Space. 13, no.3 (1995), 259-265.

UPDATE

On 30 October 2011 the famous blogger and activist Alaa Abdelfattah was summoned to the Military Prosecutor’s office, accused of assaulting military personnel, stealing military weaponry and inciting violence against the military. He is accused of being responsible for violence on 9 October 2011. Abdelfattah refused to recognize the legitimacy of the military prosecution for two reasons. First there is a conflict of interest for a party it itself responsible for this crime. Secondly civilians should have a fair civilian trial and not a military one that does not entail consultation or cassation. It is estimated that twelve thousand civilians are subjected to summary, covert military trials. As a result, Abdelfattah is held in prison for fifteen days. There is a list of activists charged with inciting violence of Maspero like the 6 April 2011 movement and Bahaa Saber. It is perverse that Mina Daniel is listed among them. Daniel was killed by military gunfire on 9 October 2011. On 31October 2011, bloggers and activists organized a huge night march from downtown to the Prison Appeal in solidarity with Abdelfattah who is staying there. No doubt the accumulation of the current regime’s mistakes will fuse another uprising.

[Acknowledgement: I want to thank Mona Abaza for supporting the idea of bringing together all testimonies in an article, Khaled Khalil for his useful blog, and Nabiha Megateli-Das for editing].