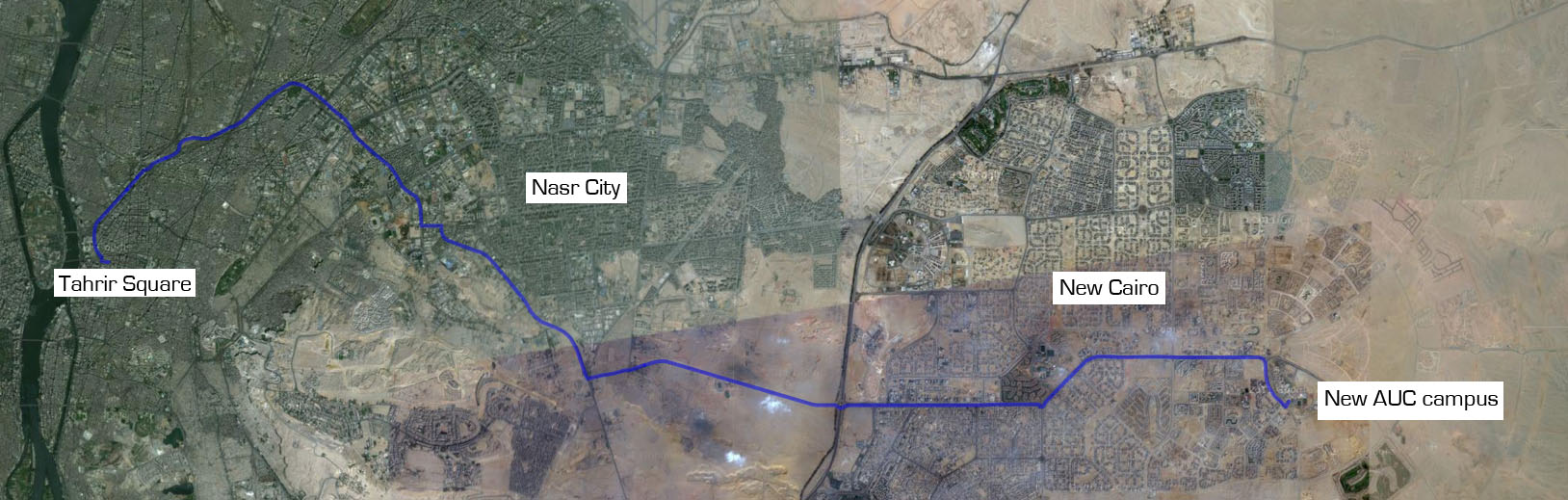

Tahrir Square is the epicenter of the Egyptian uprising and the inspiration for the global occupy movement. From here, at the gate of the American University’s downtown campus, busses depart on a regular schedule towards the new campus some forty kilometers away. From downtown Cairo, the historic nineteenth century center, the journey east to New Cairo takes about one hour without traffic. On board the air-conditioned bus students and faculty surf the Internet on their iPads, iPhones and laptops. These busses are equipped with high-speed wifi. Moving eastward across the space of the city roughly corresponds with the city’s development across time from older to newer. New Cairo is the culmination, the final destination and the Mubarak regime’s urban contribution to the city.

The Sixth of October Bridge is an elevated highway that cuts though Cairo’s historical layers heading from Tahrir Square towards Nasr City. Like New Cairo today, Nasr City was in the 1960s the regime’s mega urban planning project, a massive addition to a city that had been up until then developing organically and in smaller increments of change. The view from above the bridge is of a fading city with its historic nineteenth and twentieth century buildings falling into disrepair as a result of state negligence for half a century. Cosmopolitan mixed income neighborhoods have transformed into ghosts of their once glorious past. Buildings, ranging in style from neoclassical, art deco and modernist, are covered with a thick layer of dirt. As we move east we leave behind one kind of city for another. Behind us is a city where the street is a public space with sidewalks busy with pedestrians and buildings lining the street’s edge. Ahead of us is a CIAM-style city with tall repetitive apartment blocks pulled away from the street’s edge, where vehicular traffic dominates and the street is hazardous to pedestrians.

Down from the elevated highway, named after what is deemed by the regime a military victory on the 6 October 1973, at ground level the bus passes a series of walled compounds mostly belonging to the army. This leads to a road oddly named “the Armored Vehicles Road” referring to the kind of vehicles that rolled over protesters last October in a bloody confrontation in front of state television. Armored Vehicles Road cuts through a desert buffer zone owned by the army. The road then intersects with the city’s ring road, the beginning of New Cairo. An east-west commercial spine, Mubarak Axis, named after the deposed president Hosni Mubarak, transects the new city.

The north side of the ten-kilometer long Mubarak Axis is mostly dedicated to businesses, commercial centers, banks, office blocks and entertainment areas. The south side is mostly residential blocks. Into the distance on either side of this road are thousands of residential constructions, rising simultaneously. All buildings are detached and never share walls. Most are pulled back from the street and are fronted by fences and gates. Mubarak Axis is an odd place; it is neither a highway nor a city boulevard. There are neither traffic lights nor pedestrian crossings and there are no official means of public transport. This is a city planned for the private car but even still there are hardly enough parking spots.

The buildings on the commercial side of the road are reinforced concrete and brick clad in aluminum panels and glass to exude corporate modernity. The residential blocks on the other side are also reinforced concrete and brick structures. The construction mafia controlling the area offers clients a choice of plans and models that can then be clad with a selection of precast ornamental columns, balustrades and other Vegas artifacts. Residents, as if in competition, try to outdo their neighbors with the number of ornaments attached to their facades. These buildings are referred to in the local real estate market as villas but they are neither villas nor apartment blocks but rather a grotesque combination of the two. Aesthetically the cultural references for these constructions are the mirage cities of the Persian Gulf countries rather than Cairo. The ultimate bourgeois Islam architectural indulgence is a mammoth “house” with four giant ornamental Corinthian columns seemingly carrying a pediment in the center of which are plaster letters that read, “there is no god but god.” This is the ninety-nine cent version of Dubai minus the towers.

New Cairo is not a gated community; it is a planned expansion of the capital and part of a thirty-year program of “satellite cities” in the desert around Cairo. Within New Cairo are many gated residential compounds such as Rehab City and Katameya Hights. There are also private gated multi-zone cities within New Cairo such as the controversial Madinaty, which includes the usual apartments, villas, and services in addition to its own business district and downtown-like development. The total area of New Cairo is 264 square kilometers comprising more than half of the existing built-up area in the capital where twenty million inhabitants live. The current population of New Cairo is just over 100,000.

The Mubarak regime built on former president Sadat’s vision for the future of urban Egypt along an American model. Sadat is famous for writing in his autobiography that he dreamt for every Egyptian to have his own car, detached house and a television set. Initially state-planned desert development comprised of social housing but most remained vacant due to terrible planning, isolated locations and lack of services and jobs. While the informal construction industry flourished, laws such as rent control squeezed the middle and upper classes out of the urban centers and created a market for exclusive luxury elsewhere.

The periphery became more desirable than the center and a class exodus commenced. Much of the desert land surrounding Cairo was owned by the military and it was sold in opaque deals to private investors and development tycoons. Entire industries emerged for luxury home furnishings, luxury interiors, imported furniture as well as financing options to help buyers pay for their new home, new car and new lifestyle. The government subsidizes gas and spends little on public transport despite the fact that only 14.9 percent of households own cars. The majority of Egyptians are left out of such deals and class segregation has become increasingly visible in the urban environment. The American dream is the Egyptian nightmare.

On the return bus journey from New Cairo on the AUC bus, I see twenty men packed on the back of a pick up truck, returning from work. The labor force who toil day and night building, landscaping, cleaning, cooking for the rich stand on the side of the road waiting for privately run minibuses to take them back to Cairo. Just behind them is a “coming soon” sign for a Tommy Hilfiger store next to a Starbucks and Paul’s Bakery where elites sip on coffee that costs half the daily pay of the average worker. A democratic form of transport such as a metro would have been feasible here in the planning phase, but this would have gone against with the imperative of exclusivity.

The most troublesome aspect of New Cairo is its ambiguous relationship to Cairo proper. It remains unclear if New Cairo is a different city, a suburb, or a collection of gated communities. This was an opportunity, a tabula rasa, for the state and for the wealthy to build something new and innovative. New Cairo could have been the outcome of serious engagement with the art of place-making and urban planning. New Cairo could have been a logical expansion for a city that has been continuously inhabited for over a millennium. Instead what have been built are million dollar shanties, the result of unregulated free enterprise.

New Cairo also raises a more universal question regarding architecture as commodity and its place in society. New Cairo and the milieu to which it belongs transform architecture into trophies for the rich, mere show pieces to advertise wealth in the face of the ninety-nine percent. This confrontation is one of the reasons why Egyptians rose earlier this year and why Mubarak and his accomplices were put on trial. Ironically, the Mubarak (sham) trial is being held in New Cairo at the police academy named after him where his security apparatus learns how to suppress the population.

New Cairo is neither new in its conception nor related to Cairo’s complex cumulative urban heritage. Cairo was never a colonial city the way Algiers was, for example, where a privileged minority lived in an exclusive part of the city segregated by an army from the majority of the population. Mubarak’s neoliberal policies have in fact created a colonial city condition in Cairo where a political and economic minority fills the role of colonizers. The colonizers are backed and protected by a militarized government at the expense of the majority of the population, create zones of exclusivity, enjoy special benefits from the state, gain direct access to resources, and exploit cheap labor. New Cairo is not for all Egyptians yet government funding and planning backs it. Within it is a collection of gated complexes within which are homes or businesses that also have their own gates and walls. The only thing new about New Cairo is its unprecedented politics. Riding the bus back towards Tahrir Square, I look forward to arriving at a place I recognize as a city and as uniquely Egyptian, it is everything New Cairo is not.

[Home under construction. Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

[Homes under construction. Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

[Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

[Landscape view of residential constructions. Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

[Commercial building under construction. Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

[Commercial building under construction. Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

[Commercial building under construction. Image by Mohamed Elshahed.]

From Jadaliyya Editors:

For more on Egypt Election Watch (EEW) entries by category, click on the following links:

(1) Parties and Movements

(2) Actors and Figures

(3) Laws and Processes

To view all entries on one page, click on Egypt Elections Watch, and for EEW team members click here. Our Egypt Page can always be accessed view here.

![[Home in New Cairo. Image from Mohamed Elshahed.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/newcairofinal.jpg)