[This is the second part of Amal Hanano`s series, Portraits of a People.]

In our dictator and monarch infested region, we have become accustomed to seeing the privileged children of power, the offsprings of presidents, kings, ministers, and mas’uleen, acting as if they owned the land and the people. A few weeks ago, I spent time with a certain daughter of a Syrian president who is as elegant and gracious as a queen, but without pomp or false entitlement. Her name is Hana al-Kouatly, the daughter of Choucri al-Kouatly, the first post-independence president of Syria.

Hana’s Parisian apartment is gracious, welcoming, and refined. Damascene antiques are artfully composed on the tables with vases of fresh-cut flowers she arranges herself. The focal point of her impeccable living room is the large portrait of her father, sitting in his suit and tarboosh, his fingers intertwined, his expression gentle. Unlike the imposing images of our dictator that suffocate our public spaces, Choucri al-Kouatly’s portrait was one of calm and guidance.

Choucri bek al-Kouatly

Hana al-Kouatly is tall and thin, direct and opinionated, she speaks with authority and passion about the two loves of her life: her father and Syria. Although she has lived in Paris for decades and in Lebanon before that, she is deeply rooted in Damascus with eight hundred years of family history. When she speaks of Damascus, or al-Sham, as she calls it, her eyes shimmer with pride and sorrow. “I was born in Damascus, and I was raised in Damascus. When I first opened my eyes, I opened them in Damascus. When I first ate, I ate from the fruits of Damascus. Damascus taught us how to welcome and open our hearts to everyone. Damascus taught us to love and to love others.”

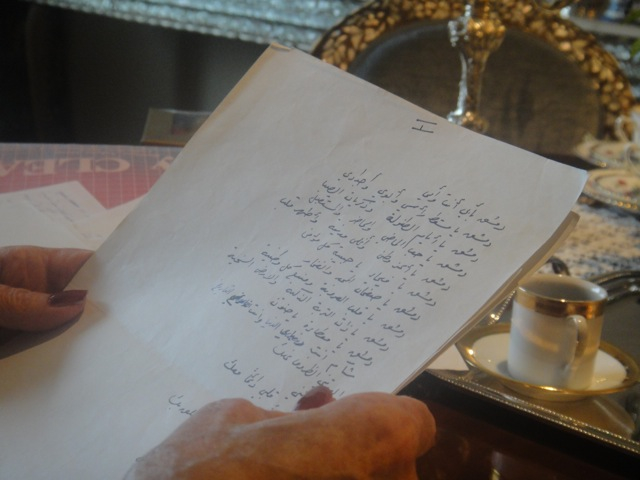

Hana al-Kouatly holding her handwritten ode to Damascus

In a year that I’ve found friendship and alliances in the most unlikely of people, meeting Hana was different. We were fundamentally similar to each other. I knew her Syria, not from experience but through the stories my grandmother used to tell me about the other era of revolutions, when the founders of modern Syria fought for a sovereign country, liberating it from the Ottomans and then the French. When I sat with Hana, the decades between us were magically erased. I have written about the gap we feel when our identity is torn between cultures and geographies, but this gap was purely temporal. She was living in the past. Time had stopped for Hana al-Kouatly on the fateful night in late June 1967 when her father and her country died. Time for my generation had never begun. And for both of us, another time began on March 15th, a time many Syrians never dared dream would happen. While I longed for her to immerse me in the past of a Syria I never knew, she longed to see the Syria of the future that fulfilled her father’s vision of a democratic, liberated, “safe abode for all.”

Today, as Hana follows the news of the Syrian revolution, on television, the internet, Facebook, and even Twitter, she continuously relates current events to the history she lived. When she watches the videos of death, torture, and destruction, she is horrified by the carnage, by what Syria has been reduced to, by what has become of her country.

Her father was the father of Syria; his story is the story of a nation. Hana views his life and legacy as a set of principles for every citizen, reminders of sacrifice, duty, and patriotism. She knows her father would have felt much pain if he could see Syria today. Pain and pride. “He would be proud of the youth today because he was a free man. Only the free can grant freedom, but those who are chained—with their selfishness and ignorance—cannot grant freedom. He was just like the youth of today when he was young. This is the second generation of Syrians rising, but this generation has no leadership. If he watched these innocent people who don’t want anything but their freedom, he would be comforted by the youth’s courage and heroism. But the country must be surrounded with a protective shield so their revolution won’t fail and won’t be taken advantage of by others. That is the fear, that is my fear.”

Choucri al-Kouatly, was born in Damascus on the 21st of October, 1891. He studied political science in Istanbul. He was twenty-four years old when he became a founding member of al-Fatat, the underground opposition group against the Ottomans. Each member was recruited by another member and sworn to absolute secrecy. He was arrested in 1916 for being a subversive activist. He was tortured to give information about the opposition but refused. In his cell, he listened to the screams of the other prisoners being tortured. One of his fellow prisoners was weak; he gave another name every day just to end the beatings, even if those names had nothing to do with the opposition. Al-Kouatly convinced a guard he had befriended to bring him a razor to shave, although it was forbidden. He prayed, shaved, and then he cut his wrist. The blood gushed onto his face. To prevent the blood from clotting, he used a quilt to press the wounds open. No one knew what had happened until his blood had seeped outside the cell. His friend, Dr. Ahmad Qadri saved his life. Al-Kouatly had feared that he would also be tortured to the point of betraying his friends, so he decided to take his secrets to the grave. After a month in the National Hospital, he was returned to prison. He was released two years later after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. His left wrist remained pulseless until he died in 1967.

Al-Kouatly was an activist, a fighter, a spokesperson, and a financier of the struggle against the Ottomans as well as the French Mandate. He was condemned to death three times before he became president. His properties were confiscated by the French in 1920, and he was repeatedly exiled, only to come back as a leader of the resistance. He refused to negotiate with the French except for complete independence. In 1936, under the presidency of Hashim al-Atassi, al-Kouatly became Minister of Finance and founded the Ministry of Defense.

He was elected president of the Syrian Republic on August 17th, 1943. The early years of his presidency, with Syria still under French occupation, were focused on diplomatic missions with his appointed Prime Minister and close friend, Sa’ad Allah al-Jabri. Due to their efforts, Syria was recognized by the United Nations as a founding member in 1945. Finally, Syria gained its independence from France on April 17th, 1946, making it one of the first Arab countries to be liberated from colonialism. Hana still remembers the grand military demonstrations; the women who had lost children in the twenty-three years of occupation marching in celebration down the Damascene boulevards. In 1949, Husni al-Za’im overthrew al-Kouatly in a military coup (the first of many more to come in the region) and exiled him to Europe. In 1955, he was elected president once more, only to resign in 1958 when Syria and Egypt formed the United Arab Republic under the leadership of Egyptian president Gamal Abd al-Nasser. Al-Kouatli’s sacrifice was unheard of: an Arab president relinquishing power for the advancement of his nation.

The life of Choucri al-Kouatly, mirrored Syria’s destiny: he struggled for liberation; rejoiced in independence; was disappointed in a failed union; and even died with Syria’s defeat in June 1967. To Hana, her father’s death is forever intertwined with the naksah. She said, “He died when we lost the Golan Heights. He said he no longer wanted to live. The Ba’th party brought disaster to Syria with the military regimes and planted the seed of evil in the country.”

She continued, weaving the past into the present, “It’s the people without principles that led to the crimes we are witnessing today. I am not against any minority, on the contrary, Syria is the cradle of cultures. For example, we had national figures like Hasan Jbara, Fares al-Khoury, and Saleh al-Ali. We never had any feelings of sectarianism against any minority. The divisions that the regime is inventing today; they are playing the minorities to destroy the majority.” In fact, al-Kouatly publicly honored the Alawite hero, Saleh al-Ali, on Independence Day, praising his courage and nationalism in his fight for Syria’s freedom.

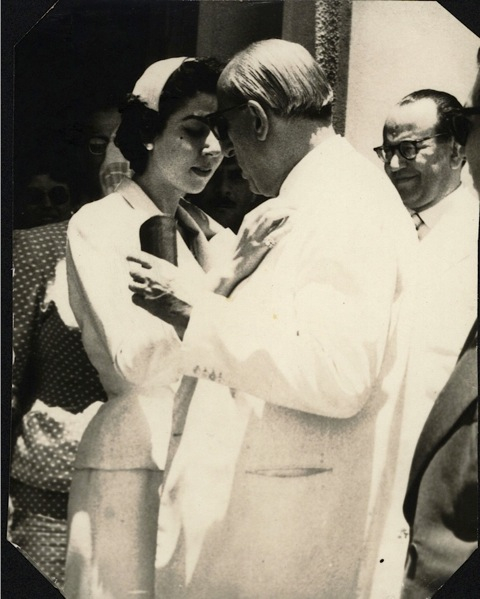

Independence Day, April 17, 1946

President al-Kouatly with Sa`ad Allah al-Jabri and Fares al-Khoury

Her father was her highest role model, and when she watched him crushed by Syria’s defeat it was “like looking at the sky and realizing that it has fallen. The fall of the Golan felt as if it had fallen on our house. The Golan fell on us.” On the day of the naksah, he was watching television in his Beirut home, as Fairuz sang al-Quds, a song about Jerusalem. He said to his wife, “Jerusalem has become a song. We tried protecting it, but now it is a song.” Then he said, “When I die, bury me in Damascus among my people and family.”

Two weeks later, on Thursday June 29, 1967, Hana was listening to music before going to visit her father, “It was the last time I would ever listen to music that way.” She arrived to her parents’ home and found him on the sofa with the doctor. He told her, “God bless you my daughter, tell them to take me to my bed. I want to die in my bed.” But he was taken to the hospital, for an emergency operation to stop his massive internal bleeding. She told her father after the operation, “You used to say you could see the moon on my face. Look at my face now, maybe God will look at ours.” He died minutes later. “His sorrow killed him, his sorrow for the land he had sacrificed everything for, his sorrow for the people he had fought for.”

President Nur al-Din Atassi originally banned al-Kouatly to be buried in Syria, but King Faisal Bin Abdul Aziz mediated and the family was granted a civic, unofficial funeral in Damascus. The funeral procession left Beirut and was stopped in Shtura, at the Syrian border, where they waited for two hours until permission to enter the country was granted. The Ba`th regime tried to use the weak excuse of Soviet Chairman Podgorny`s visit to deny al-Kouatly`s burial in Damascus and his postmortem entrance to Syria. In reality, the regime still feared al-Kouatly due to his popularity, even after his death.

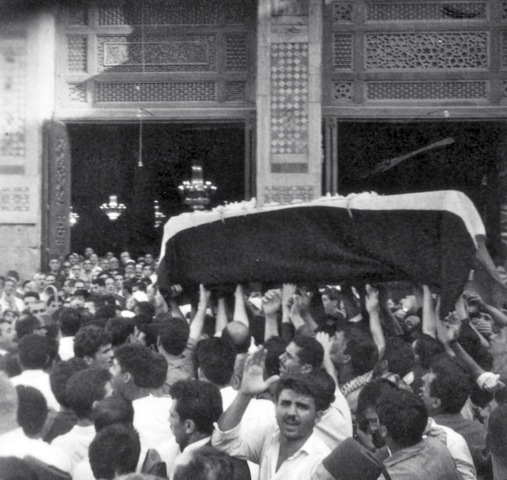

The road to Damascus was lined with thousands of people on both sides with their hands open, reading al-Fatiha, and crying. When they entered the city, they were met by Zuheir al -Khani, the government representative who told the family that the procession must continue by car and that walking to the cemetery was forbidden. As they moved slowly though the streets, they were surrounded by crowds chanting “Welcome Choucri bek, we missed you.” When they stopped in front of the parliament, people called, “This is your building, this is what you built. This is freedom, this is Damascus.” At the Hijaz station, the people broke the door of the ambulance and pulled out the coffin. Al-Kouatly’s corpse glided over a sea of hands, “dancing as if in a wedding, floating on their fingertips.” She says, ”Who were those people who grabbed my father and wanted to carry him? It was the youth of Syria, who even didn’t know who Choucri al-Kouatly was, but they knew what he represented.” They prayed for him in the Ummayad mosque three times, and twice more in other mosques, ending at Bab al-Saghir cemetery in his beloved al-Shaghour. He was buried in the same neighborhood he was born. The government representative, al-Khani, stood to speak but the crowd silenced him, calling for Hassan, Choucri bek’s son, to speak instead. He said, “This is your son, your brother, and your father, before he was my father. He is from you and of you.”

Al-Kouatly`s coffin "floating on fingertips" in Damascus

His son’s words were true, for his father always placed Syria before his family. He used to tell his family, “I am the servant of the nation, I am the servant of the people. You are the last people to come.” Hana remembered asking him, “Why are we the last?” He said, “My daughter, you want to be the reigning lady?” She replied “Why not?” And he told her, “The head of the tribe is the one who serves them.” Once, Hana asked her father for money, and he told her he didn’t have any. She replied, “What kind of president is broke?” He became very angry and said, “This is not our money, this is the people’s money.” She lamented, “I’ve never seen a president who refused to take a salary, except us. I’ve never seen a president who leaves the presidency and doesn’t even have a house to live in.”

President Choucri al-Kouatly and the First Lady with their children and grandchildren

Hana’s description of their life as Syria’s ruling family, a family burdened by the presidency, moved me. Despite the controversy over Choucri al-Kouatly’s political history, there are many desirable aspects to our first president, ones we as a nation may even envy today. I wish we had a president who studied politics, instead of a doctor who apparently forgot the first rule of medicine, or the first rule of humanity, do no harm. I wish we had a president who would rather die than be a traitor to his people, a president who would rather step down for unity than torture an entire nation for absolute power. I wish we had a president who left the presidency poorer than when he took office, instead of a president who, along with his extended family, squandered our national resources. When al-Kouatly voluntarily left the presidency, he famously told his successor, “I leave you with a population where everyone thinks they are a leader.” Leaving words of wisdom even to our fragmented opposition, because some things never change.

Hana believes, “Every person big or small is an ambassador for their country. We are all portraits of our country, in our words, culture, and tradition. My father sacrificed us for Syria. This president is the son of the president that cursed Syria. He bears responsibility for what is happening. But I don’t blame him, I blame the people who clapped when they changed the constitution. We fought the French, kicked them out, but we were honorable opponents and they were foreign occupiers. Today we are fighting one of our own, who attacks the people and the children. That is what is horrifying.”

She talked about a Damascus I had never seen, a Damascus that no longer existed. This is becoming a trend when speaking to Syrians in exile. Their country has literally disappeared. Now when she goes back, she stays in a hotel, because they “have nothing in Syria, no home, not even a wall.” Eight hundred years in a city, and nothing to show for it. Twenty years ago, a man at the hotel asked her, “Is this the first time you visit Damascus?” She replied, “This Damascus, yes, it is the first time I visit it.”

She visits her father’s grave every year on the 17th of April, on Independence Day, on “the day of freedom, Syria’s birthday was his birthday.” Two years ago, the last time she was in Damascus, she walked through her old neighborhood, now in ruins. She noticed there were no celebrations for Independence Day, that many people didn’t even know what that day meant. In the cemetery, she felt this was the Damascus she knew, filled with all her loved ones buried under the ground. In the taxi back to the hotel, the radio was playing skaba ya dumu’ el’ayn skaba, a traditional song with a poignant refrain, “let the tears rain,” and she did. This same song is today’s anthem of Syria’s martyrs, performed by men swaying arm in arm, in tightly formed rows between buildings, singing for the martyrs, singing for Syria, singing under the threat of bullets, singing through the rain of tears.

Before I left, I posed with Hana under her father’s portrait. It’s a picture I will always treasure, one I know would have made my grandfather—who had fought with Syria’s heroes and who died when I was a baby—proud. I never felt as close to the grandfather I never knew than during those moments sitting under Choucri bek al-Kouatly’s portrait. The next day, she told me she had found a picture of her father, my grandfather, and Ibrahim Hanano. I smiled. We were both our fathers’ daughters, stitching the past with the present, the collective with the personal, history with memory.

Hana and her Father

Hana and her Father`s Portrait

When I asked Hana what her dream was for Syria, she spoke slowly, “I dream to have a small house in old Damascus, in al-Shaghour, to go back to our roots, to go back to a life scented with the trace of Damascus, scented with the spring of Damascus. I dream to see the faces of the Damascenes, the ones I know and the ones I don’t. I miss the bakers and the butchers. I miss the scent of the spice market in al-Bzruiyyeh, I miss the scent of the soil of al-Shaghour when it is misted with water. I miss the apricot blossoms and the sheep in the Ghouta. There is no longer a Ghouta. I wish I could live there if only for a year, and open my door, so everyone in Damascus would know that this is his home, this is his place. I want to live in the heart of Damascus and die next to my father.” She began to cry. “When I see the Independence flag raised and fluttering over my Syria, my heart flutters with it. It is difficult for someone to be without a country.”

She sits in her Parisian apartment, wanting for nothing yet having lost everything that mattered, her father and her country. She watches this new Syria, with youthful hope and maternal concern. And she waits, to see if the day will come when she can go back to the Damascus she once knew, to al-Shaghour, or as she calls it, “Paradise.”

A Speech by President Choucri al-Kouatly in 1956: