[This is the third part of Amal Hanano`s series, Portraits of a People.]

In the field of evolutionary immunology, “it is important to recognize that every organism living today has an immune system that has evolved to be absolutely capable of protecting it from most forms of harm; those organisms that did not adapt their immune systems to external threats are no longer around to be observed.”

His story begins on March 5th, 1984, an ordinary Damascus morning. He was on route to university, where he was a second year electrical engineer student. He decided that morning he would read Ahmad Shawqi’s play, The Death of Cleopatra, on his two hour bus commute from al-Mezzeh to the university. He also brought his small English dictionary to study during the often boring lectures. At his destination, he saw a double line of students waiting to be searched before entering the building. He thought, “I feel sorry for the guy who is going to be taken.” He knew the lines meant the mukhabarat were looking for someone specific. After passing through the doors, someone called him by name, he turned, and a man said, “We need you for five minutes.” He felt “his heart drop to his feet.” After a few hours of waiting and interrogation, he was blindfolded and placed in a car. He thought he was on his way to General Intelligence in Kafar Souseh, outside Damascus, but he wasn’t. Instead, the car took a cross-country detour to a prison in his home town, Hama.

He would disappear for the next twelve years, touring the depths of Assad’s dungeons, in Hama, Tadmor, and Sayd Naya. Bara Sarraj was twenty-one years old.

Bara and I are both Syrian, but we may as well have been from different planets. When we first met, there was an unspoken, suspended disbelief between us. Nothing but the revolution could have joined us. It is one of the positive outcomes of this bloody uprising: the mixing of forces which never knew of each others’ existence. Bara’s thin, kind face is permanently marked with traces of fatigue. It’s no wonder; he didn’t sleep well for twelve years, in addition to his insomnia during the last nine months. He is known in Twitterworld as @Tadmor_Harvard. His 1,849 followers address him with a respectful Doctor Bara. To me, he is simply Bara, and to him, I am “ukhti,” his sister.

In Syria, we all know there are people in jail for nothing but their dissident thoughts, and sometimes for nothing at all. Bara is an anomaly, the story of survival, the one who emerged intact, determined not to allow his prison story to define him or to limit his future. But he is literally one in tens of thousands. The less fortunate ones, when (or if) released, are banished to the margins of society that must be as lonely as the corners of their prison cells.

Although Bara is from Hama, when he talks about the 1982 massacre, he is not as moved as the rest of us who speak of “the events” in dramatic whispers. He says, “Many died, thousands died, but the dead are dead. What about the rest of us, the living, the ones who were forgotten? Who was there to defend us?”

During his first year in prison, Bara kept a list of names, dates, and events in his mind, preparing a detailed account to tell his mother when he was released. When the first year passed and he wasn’t released, and the second year seamlessly turned into a third, he began reciting the lengthening list to himself, so he wouldn’t forget. After his release in 1995, he lived in Damascus for a year before coming to America. He didn’t dare write a word then, because he constantly feared a surprise visit from the mukhabarat. In America, Bara wanted to start a new life, far from prison and its traumatic memories, but in 2000, after graduating from the University of Illinois, he realized if he didn’t write everything he had memorized, the list would be gone forever. In one month, he documented it all, forty pages of the essential facts, and filed it away. He left out his personal experience because, as he says, “those details are my life, and that will never be erased from my memory.” I think the details were too painful to write; he could never get past a few pages before giving up. This year, his walls of repression broke down and the memories finally flowed.

Bara opened his Twitter account on his birthday, February 2nd, to follow the Egyptian Revolution. His first tweet: “I wish our Egyptian brothers will forgive Mubarak.” He explains, “I wanted to see the presidents leave the way the American presidents leave, peacefully. I wished we had that, but then I erased it because it is an impossible wish when you see what Mubarak did and what Assad does. How can I ask the Egyptians to forgive Mubarak and I cannot forgive Assad?”

Immunology is a science but philosophically, it is rooted in protecting the most basic human need: shelter. From birth, after leaving our first home, the sealed womb, humans continuously seek for protection against the harms of the world: disease, climate, the environment, and sometimes, ruthless dictators.

He began his memoir, From Tadmor to Harvard, on March 25th. After sixteen years of silence, he thought no one would ever care about his story. But as he heard stories of a new Syrian generation of detained young men and women, his own story began to haunt him once more. Twitter was the perfect medium to communicate the trauma of memory. Bara tweeted his story in bite-sized sentences which reflected the pain of releasing the details. His loyal followers were hooked and encouraged him to continue the story. He finished the book in just over two months, on June 6th, his 27th anniversary of entering prison.

Bara`s Tadmor and Harvard IDs

From Tadmor to Harvard, is a journey through the dark underbelly of Syrian society, the prisons and the torture cells that were essential to make the upper world run smoothly, both interdependent machines of fear. He frames his memoir as a universal story, “one of thousands of prisoners of conscience who were arrested by the hands of those with no conscience, in any country where the citizen is worthless, including Syria.”

While he experienced several of Assad’s prisons, the most horrific was Tadmor. The city of Tadmor or Palmyra, is the jewel of ancient Syria. An archeological treasure, Palmyra is Syria’s prized tourist attraction: an authentic site of Roman ruins set within an authentic Arabian desert landscape. This isolated location, far from the cities and population became home to Tadmor, the prison, where thousands of political prisoners were tortured and executed. On June 27, 1980, Rifaat al-Assad ordered the execution of a thousand prisoners in one day. (This is a very conservative number, it may have been up to four thousand. It also took two weeks to clean the prison from the bloody aftermath.) When a prisoner entered Tadmor, it was unlikely he would leave undamaged, or even alive. According to Bara, Tadmor is a synonym for fear, in all of its definitions: terror, horror, panic, dread. “Language cannot describe it. Fear is the internal sensation when you physically feel your heart between your feet and not in your chest; fear is the look on people’s faces, and their darting eyes when the time for the torture sessions comes near.” Bara learned to be first in line to go to the torture cell, because “the fear was worse than the pain.”

He is still haunted by the sounds: creaking doors, rattling keys, gunshots, the dreaded shuffling of heavy feet in the corridor, the sound of torture, the sound of screams. Tadmor, was “the symphony of fear.”

His account describes the tools of torture in detail like, the dreaded dulaab, a car tire used to fold the prisoners’ bodies into human contortions while suffering intense beatings with the kirbaaj, a one meter long rubber belt, embedded with metal pieces, used for fixing tank wheels, that dug into their flesh and scarred their bodies, or the technique of hanging prisoners from their wrists for hours, or beatings while being forced to write their confessions of treason against the country, or the falqa, the continuous whipping of the soles of their feet. After enduring a falqa session, they would hop on their damaged feet to combat the swelling. If they were able to, then the pain would only last two weeks, but if they didn’t, the skin would crack and break open, leading to pain that would last for months. Most times, torture sessions would end when the prisoner lost consciousness and would be dragged by the guards back to the cell. The prisoners learned to differentiate how their friends were being tortured by their screams. Every time the door of the cell opened, someone suffered a beating, to bring in food, to take out empty trays, to go to “recess” in the courtyard. The door of the cell was terror itself, a continuous breach to their immunity.

Bara demonstrates dulaab technique at a Walmart.

The small communal cells were packed with men, holding anywhere from 40-220 prisoners, with less than a foot width for each, so they learned to sleep on their sides. Each time Bara was transferred from one communal cell to another, the prisoners organized themselves by specific responsibilities. There was the Protecter, the Doctor, the Meal Organizer, the Sound Controller, the Sanitary Official, the Laundry Official, and the all-important Minister of Lice. They exercised a system of democracy that was nonexistent outside the walls of prison. They also nominated someone to be president of the cell, the Prince, to manage internal affairs, to solve problems between the prisoners. The Prince was elected by popular vote and had a finite term. Maybe this is why these men were in Tadmor to begin with, so their dangerous, fundamentalist notions wouldn’t infect the rest of us.

Bara was the first elected Prince. His first duty was to create a fund for necessary medicine, which they had to buy from the prison doctor. He recognized the difficulty of ruling so he resigned after two months, but was reelected. In his second term, in a stroke of brilliant calculation, he decided to ban smoking. He quickly fell out of popularity and was soon overthrown by the citizens of the cell. He was able to relax and watch the new Prince, a non-smoker, sit and puff cigarettes with his constituents, while listening to their endless complaints.

Despite the daily beatings and constant humiliation, the prisoners found subversive ways to outwit the guards and protect themselves. Once, they invented “makeup” for the youngest prisoner, a teenager who had received an especially severe beating the day before. They feared the next round of torture would kill the boy. So they used soot and threads from their clothes and artfully pasted them on his face and back. The next day the guards came back to take the boy for more torture. When they saw his disfigured face, they turned away disgusted, and left him alone.

Surviving every torture session would fill them with joy, “as if they were paying off a tax they owed Syria.”

The first months in prison they hoped for an eventual release. Then one day, the guards set up the nooses in Courtyard 6. The periodical hangings began, and their optimism slowly evaporated. Each prisoner going to be hanged would cry out his name, so the rest would know of his fate. Families were often not told the status of their sons, where they were, or if they were dead or alive. It was up to the remaining prisoners to keep a record of the dead. Once, in a Damascus detention center, Bara witnessed a man from Idleb enter their cell. He had been “under investigation” in Tadmor for four years. He was shocked to see his father, an elderly man in his eighties, detained as well. The father wept with joy and sorrow, repeating over and over, “I thought you were dead.”

Immunity is a war between cells and attackers on the cell. In the battle over immunity, sometimes the disease overcomes the body. Our revolution, at its essence, is a collective battle to protect our breached immunity.

When he came to America in 1996, he wanted to become a truck driver for financial independence and because he was attracted to the idea of driving long distances on open highways to compensate for his twelve years of living in a cage. But his true passion was biology, a subject he had loved since he was a child. A future in biology became his dream in Tadmor. “My behavior in prison was to completely isolate myself from the people. My mind was with my family. My mind was outside. That’s what I decided. And that was a very good technique for the first five years. You have complete immunity, full resistance. I still remember saying to myself, ‘If God allows, one day I will go to the end of the world and live in a scientific lab until I die.’ I remember the word ‘lab’ although I was an electrical engineer student. Because in my mind, the scientific lab is a quiet place. I am a quiet person and I didn’t like to be with many people in the same room. That in itself was torture. Though later you feel it was a mercy, in some ways.”

So how did he cope with the forced, crowded environment in prison? He says, “I learned how to become social in Tadmor, people taught me that. I used to be moody. Once when I was in Room 13, the very first room, I was praying fajr and one man stood behind me. I was upset. I didn’t want anyone to pray with me. I wanted to be alone. So when we finished, I turned to him and said, ‘At least take my permission.’ He looked at me, ‘Bara, if I only knew you were like this. I promise you, I will never pray behind you.’ And time passed. That man was executed ten years later, and I still regret how I treated him. So you learn from your mistakes. One day a man came to me and said, ‘Bara, let me tell you this, we don’t function according to your mood, one day you are joking and one day your electricity is off. You decide, either always off or always on. That taught me, you have to be nice to people. Later you realize that you like them, and later you realize this is my real family. I said that in Sayd Naya, you learn the real brotherhood in Tadmor.”

After college, he specialized in immunology. Bara wanted to learn how cells protected themselves and the body. “I wanted to study immunology, to understand what went wrong in Syria. I believe we can derive a lot of lessons from this defense department.” In fact, he has coined a term for this area of study: Immunopolitics.

“The hallmark of inflammation is infiltration by white blood cells. In transplantation, white blood cells infiltrate the graft, because the white bloods cells sense there is something wrong and they come to fight, and create havoc. Inflammation is a side effect of your body fighting outsiders. So it hurts you a little bit until the inflammation is under control. The body will not accept the outsiders no matter what you do, unless you suppress the immune system with immunosuppressant drugs that you have to use for life.”

White blood cells or leucocytes, scanning electron microscope image.Source: National Cancer Institute

Bara calls his fellow prisoners the “white blood cells of Syria.” What the Assad regime has done in the name of control, is kill our national immune system to weaken the country. “Assad, the father or the son, what they are doing is target those white blood cells, whether in Tadmor, or the educated professionals in the unions, or the journalists, or the intellectuals, or the leaders of the demonstrations. Bashar is like a virus, he knows what he is doing, weakening the immune system, because if those cells are eliminated, the body cannot fight back. This guy will stay.”

But there are ways to combat this virus, Bara says, “Ghassan was taken when he was fifteen, and was the last to be released when he was forty. I told Ghassan, ‘I’m really happy that I met you. I don’t regret being arrested just to know you.’ This is thymic education: teaching the cells how to behave, to know each other, and to know their enemy by mixing. It’s an amazing term in immunology.” This concept of becoming stronger through mixing, instead of separating from each other, is a powerful one.

Bara once told his friend in Room 13, “I will go to Oxford, just wait and see.” But after completing his PhD in immunology, he continued his post-doctorate studies at Harvard instead. He once asked me, “Do you know why I had to go Harvard?” I shook my head. He replied slowly and I felt the weight of each word, “Because I wanted to prove to my mother that I was not a wasted life. I wanted my family go back to normal. And I wanted to send a message of defiance to the intelligence heads, Ali Douba, Hisham Ikhtiyar, and Hafez al-Assad himself: I am doing fine.”

When I ask him, after all these years, if he still considers Syria his home, he replies, “The very first book I ever bought, when I was seventeen, was called The Outsider, by British writer Colin Wilson. He used to write his notes in the train, as I do now. That book attracted my attention, I still remember the bookstore in Hama, next to the Ba’th party headquarters. That’s how I always felt, an outsider. Maybe it’s a dichotomous feeling, because with this revolution, I finally felt I belonged. When you see the Syrians, you really love them. Back then, I was just a bystander. I remember how many times I travelled from Hama to Damascus, but I never stopped in Homs. I regret now that I never stopped. Homs was never the destination. I was born in Damascus, so I love Damascus, especially after prison, but Hama is my childhood. I am Syrian, my home is Syria. Now, I will go back, to any place in Syria, from Aleppo to al-Qamishli to Daraa, I am willing to go back, work at a university, and offer my experience. That would be the ultimate goal.”

In Arabic, Bara’ means innocent; Bara, paid a high price for his innocence. Today he sits in his white coat, in his quiet lab, researching ways to protect transplant patients from rejecting their foreign organs. I imagine him in his lab, peering into the microscope, searching for the cure to our Syrian disease.

Bara does not write to move us (although he does); he writes to document facts. His memoir is a carefully constructed document. Each chapter begins with a Google Earth arial photograph of the prison, as evidence. He outlines the cells in red, numbering them, labeling the courtyards. He had always wanted to see where he was imprisoned because they were forced to wear blindfolds, tammasheh, when they moved from one place to another. Even in their sleep they were forced to wear their leather or cloth blindfolds because, he says, “Tadmor never sleeps.” He developed a special ability to peek under the fold, through the space between his face and the cloth, that helped him see his surroundings. “You wear it when you are walking, and they will drag you, your hands are behind your back, and your head is 90 degrees with your body. Many people were beaten because of the blindfold slipping off in their sleep.”

Through his scientific approach, I think Bara wanted us to see what was in front of our eyes all those years. He needed to prove to us where they were and what they did. He needed to prove to us they existed. The prisoners were blindfolded to prevent them from seeing because they were not blind like the rest of us. We had internal blindfolds tied on tightly.

When I read the memoir, I find myself mapping my own life against his precise timeline: when he was detained, I was in grade school; when he was released, I was in university. And all the years in between and after, we were separated sometimes by thousands of miles and others by hundreds, and for a few years, there was less than a mile between us. If I had passed by Bara on the street, I would have never recognized him. The real distance between us was infinite; for the blindfold was still on.

During the grim Syrian years of the late eighties, when Bara was in Tadmor in his patched prison clothes, I was in school in my pressed military uniform. While he and his friends were forced to chant for Hafez in the prison courtyard, my classmates and I were chanting for the Father, our leader for eternity, in the concrete school courtyard. Our synchronized bodies performed the same military drills, him in the cell, us in the classroom. And at the end of every morning recitation, we made the oath: denouncing the treacherous Muslim Brotherhood. We were forced to say words we did not understand, because we were scared of the vicious military trainer, who inspected us with her hawkish eyes, for a trace of mascara, a forgotten cap, or a glimpse of white socks instead of the mandatory black ones, offenses punished by slapping, pulling hair, or cursing. So we chanted for the leader and against the traitors, not knowing we were betraying our brothers in prison. Our voices mixed with their screams. Our voices were part of the symphony of fear.

We dismissed those words and chants as meaningless. Perhaps they were, but they were not harmless. We were young but not innocent; we knew we were lying. I knew I was lying. I wish I could go back in time, and swallow those words, those lies. I wish I could erase my voice from the national chorus. If only to save him from one whipping, one beating, one moment of pain, one moment of loneliness. If only I had ripped off the blindfold.

Someone told me recently, that sometimes it feels that we are not fighting for freedom, but we are paying the price of our forty-one years of criminal silence. With every injustice today, we are slowly paying for those we forgot to defend, the ones we forgot existed. What is the price we have to pay for Bara’s suffering? For the suffering of tens of thousands of other Baras? For the 11,000 men who were executed in Courtyard 6 in Tadmor?

Tadmor was closed in 2001, at the beginning of Bashar’s presidency, perhaps to end one of his father’s darkest chapters, perhaps it had become obsolete—there was no longer a need to fight a defeated people. On June 15, 2011, Tadmor opened its gates once more to welcome the first wave of 350 people who had participated in the uprising. Today, Syria’s prison cells are packed with the next generation of innocents.

.jpeg\)

Bashar al-Assad in Tadmor, with the prison to the left and Palmyra ruins to the right.

On June 21st, in his third speech since the revolution started, Bashar al-Assad said, “Conspiracies are like germs, after all, multiplying every moment everywhere. They cannot be eliminated, but we can strengthen the immunity of our bodies in order to protect ourselves against them.” But what the president fails to understand, is that his father already vaccinated us against fear. A vaccine is a function of physiological memory. The first time around, the body gets the disease, but if it survives, the second time around, the body will defeat the same disease; it has a stronger immunity acquired from memory. As usual, his logic is flawed and in reverse: we are now immune to him.

Sometimes late at night, when I can’t sleep, I find Bara on Twitter. During the day, he is busy debating others on policy and politics. But at night, his prison memories haunt him once more, and through his words, they haunt us as well. His memories have seeped into us, marking our own with shame and guilt. He may think he is alone, tweeting into the void, but he is not. We are all measuring time now, etching short lines into the cellular walls of our memory, his 11,636 tweets, his 4,276 days in prison, and now over 5,000 dead. And tens of thousands in prison today. Men and women as young as Bara was, as smart as he was, the ones who stood up for the rest of us, the ones who might have gone to Harvard, but are enduring the dulaab, the beatings, the humiliation instead.

When Bara and I speak, there is a suspended, unspoken request that lingers in my mind, a plea I do not dare ask: forgiveness. This is a portrait in disguise that I wrote for my brother, to tell him that we are still salvageable, that our years of criminal silence did not completely ruin us, that our blindfolds are off, forever.

It is a law of nature that every relationship between two organisms, no matter how pure, serves a purpose. I don’t know what, if anything, my friendship means to Bara; but I know, I take from him more than I could ever give back. Beyond his unconditional acceptance and soft-spoken wisdom, Bara gives me reassurance. His survival and success, against the odds and beyond expectation, reassures me that there is still hope for us in this darkening Syrian nightmare that threatens to rip our country apart. This hope—as fragile and as resilient as the thin wall of a cell—is that we will somehow reemerge on the other side, our spirits bruised but not broken, our immunity breached but still intact.

That we will emerge as survivors.

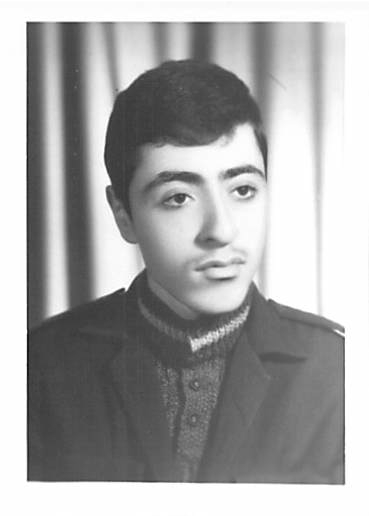

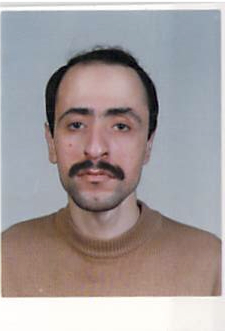

Left: Bara Sarraj, 21, before entering prison. Right: Bara Sarraj, 34, after release from prison.

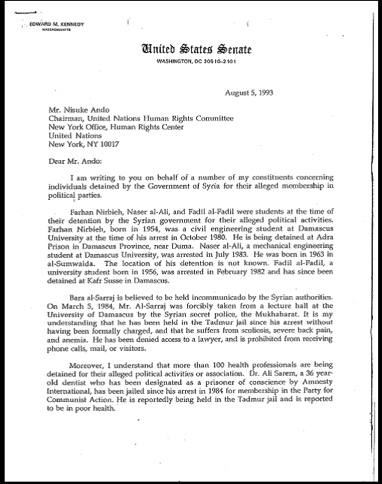

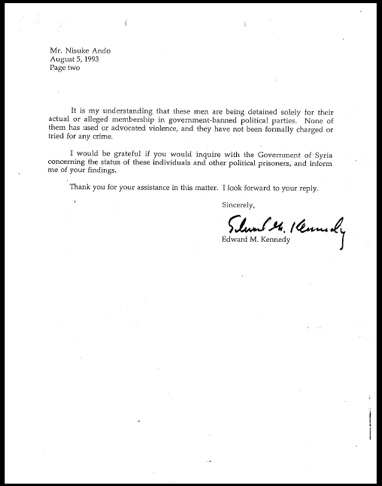

Letter by Senator Edward Kennedy written on behalf of Bara Sarraj

and other political prisoners in Syria.

Aerial view of Tadmor Prison. Image courtesy of Bara Sarraj.