The city of Mansoura is scheduled to vote on 3 January 2012 in the final round of Egypt’s lower house parliamentary elections. Below is a primer on the city’s upcoming contest by way of a photo essay (for more on election rules and dates, click here).

Mansoura, spoken proudly of by locals as Egypt’s “third city” after Cairo and Alexandria, is situated along the Damietta branch of the Nile River, 120 kilometers northeast of Cairo in the heart of the Nile Delta. As the capital of Daqahliyah, Egypt’s third most populous governorate, Mansoura boasts approximately five hundred thousand residents. Unlike industrial centers of the Nile Delta such as Tanta and Mahalla, Mansoura is primarily known for its agricultural production, due in large part to the region’s vast tracts of surrounding arable land. Mansoura is also uniquely famous for its medical school, particularly the Urology and Nephrology Center, headed by world-renowned surgeon and prominent political figure Dr. Mohamed Ghoneim.

Running the Numbers

Daqahliyah is allotted thirty-six seats in the Egyptian parliament, including twelve seats allocated through individual candidacy races in six districts (two seats per district), and twenty-four party list seats divided across three districts (eight seats per district). The city of Mansoura is located in the party list district #1 and individual-candidacy district #1. Altogether, this district is comprised of ten parliamentary seats—two seats for individual candidates and eight seats for list candidates.

Above is a map of all seven divisions of Daqahliyah’s party-list district #1. The zones encompass Mansoura and several outlying areas. In other words, any candidate running in the district outlined above is effectively competing in all seven zones. By comparing distances on the map between cities, one can clearly see the immense area list candidates need to cover to reach their constituencies. According to electoral rules, each list must field the same number of candidates as there are seats available to win. Therefore each list in this district is composed of eight individuals who must campaign in an area over sixty kilometers north to south.

The above image displays the three divisions (numbered in yellow) composing the first electoral district in Dakahlia for individual candidates: Mansoura-first (1), Mansoura-second (2), and Mansoura-center (3). As with the list map, anyone running in the district outlined above must compete in all three zones. Circled in blue is the city of Mansoura, which is split between Mansoura-second and Mansoura-first. The remaining vast—and almost entirely rural—Mansoura-center portion of the map in area 3 again exemplifies candidate complaints that district lines are too large for efficient campaigning.

Band of Brothers

In Mansoura, as elsewhere around the country, a chaotic array of campaign banners hang, at times overlapping one another and competing for voters’ attention. The photo below was taken in the first week of November when, just two months before the start of elections, a torrent of campaign propaganda began flooding the city in large numbers for the first time.

Broadly speaking, over the past few months only the Muslim Brotherhood has consistently found creative ways to cut through paper propaganda in order to connect with voters in a meaningful way even before the legal date for the beginning of election campaigns.

Below, in a photo taken on 26 October, Brotherhood members throughout the city served as stand-in traffic police after the city’s regular police force went on strike.

The Brotherhood, through its own Freedom and Justice Party, has also shown its ability to take national campaigns and tailor them to local sensibilities, and thus, voters. Below, for example, a banner invites Mansoura residents to participate in a special Eid Al-Adha (Muslim holiday) prayer sponsored by the Muslim Brotherhood. Of note, the keynote speaker is Yousry Hany, the organization’s premiere Mansoura politician, and individual professional (‘fe’at’) seat candidate (for more on the worker/farmer quota in parliament, click here).[1] Hany, a widely respected Islamic scholar, was also a candidate in Mansoura’s highly controversial 2005 parliamentary contest, in which his seat was co-opted by the former ruling party. Well liked by individuals across the political spectrum, Hany is believed to be the city’s strongest professional candidate, and thus the centerpiece of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mansoura campaign.

Moreover, locals like Hany have their notoriety leveraged by the Muslim Brotherhood’s organizational and financial firepower. In order to optimize the number of people present for their lead candidate’s Eid prayer, for example, a bus ride is arranged for anyone wishing to attend, gratis, as seen below.

Above sign reads: “Free transportation to the Eid prayer at the governorate’s Thawra (Revolutionary) Square (sponsored by the Muslim Brotherhood)”

And following the prayer, the organization throws a colorful street celebration, capitalizing on one of the city’s rare mass public gatherings. Below, balloons and toy trucks are handed out indiscriminately beneath banners introducing the district’s candidates.

After the Eid Al-Adha holiday week, and as some of the city’s liberal and independent campaigns are just getting off the ground, the Muslim Brotherhood follows up with regular membership drives. Below, a banner hangs outside of one such drive in Talkha, a small industrial city just across the Nile from Mansoura, yet another location where the latter city’s candidates must extend their campaigns.

Banner reads: “Freedom and Justice Party: Founded by the Muslim Brotherhood for All Egyptians. Get to know us. Join us. Campaigning for the good of Egypt”

Outside the tent, an enthusiastic organizer approaches us with the zeal of a recent religious convert. His flawless three-minute monologue on the party’s platform, however, has no such theological undertones. Bubbling over with excitement, the organizer notes that not only has the party been quick to sign up new members – 175 and 150 respectively in the last two outings alone – but many new recruits have become instantly immersed, volunteering to work at ongoing events the same day they sign up. Below, new members register with the party.

As the above anecdote would suggest, organization begets further organization. And when there are no major events such as Eid Al-Adha to take advantage of large crowds, Freedom and Justice Party coordinators simply create their own impromptu gatherings.

Below, a “dream board” is erected on a main street across from Mansoura University. Pedestrians are handed post-it notes to scribble future hopes, as organizers are offered another chance to connect with the public.

But as the below note would suggest, not all of the city’s residents are lining up behind the Freedom and Justice Party’s highly organized campaign march.

The green note in the center reads, “I wish the Muslim Brotherhood would disappear from Egypt.”

The Lot of the Local Liberals

The question for many voters and political analysts then is who, if anyone, is the alternative to the Muslim Brotherhood. In some regions of Egypt, particularly urban districts of Cairo and Alexandria, the leading liberals seem to coalesce around the Egyptian Bloc’s electoral coalition. Interestingly, their presence in Mansoura is minimal. Though the Egyptian Bloc is running in the party list race, only the Bloc’s Al-Tagammu Party candidate for the single-winner race in district #1, pictured below, seems to have any visibility. Somewhat telling, the Egyptian Bloc is not contesting the city’s individual professional seat.

But the low visibility of the Egyptian Bloc is explained less by the categorical absence of liberals in Mansoura than of their base being subsumed by the Revolution Continues Alliance, whose national campaign banner is pictured below. It reads: “With your support we will achieve security, freedom, and social justice.”

Although the Alliance’s campaign banners line the city in rough parity with the Muslim Brotherhood’s posters, their actual presence is far less obvious.

Once per month in a local Mansoura bookstore, candidates of various political orientations come together to discuss their platforms. Below, Mohamed Shabana, the candidate topping the Revolution Continues list presents his program to the crowd at one such event.

Well-meaning civic engagement events such as these, however, do not appear to reach voters to the same extent that campaigns put on by the Muslim Brotherhood do. A simple zoom out of the room underscores this point:

Despite this overwhelmingly negative political assessment, liberals in Mansoura remain optimistic about their chances of taking a large number of seats in the district’s party list races. The cause for such seemingly unwarranted optimism is one of Mansoura’s most famous residents: Dr. Mohamed Ghoneim, seen in the bottom right corner of the following campaign flyer, ostensibly pondering the liberals on “his” list.

Dr. Mohamed Ghoneim, currently professor and chairman of the Department of Urology at Mansoura University, is the driving force behind the Revolution Continues Alliance in Mansoura. While many of the list’s liberal candidates are not well known to Mansoura residents, Dr. Ghoneim remains a near legendary personality throughout the city. To leverage this influence, Ghoneim’s face is prominently displayed on nearly all campaign signs. The Alliance hopes that the surgeon’s celebrity endorsement will capture the “non-Islamist” vote, if not dissuade some of those who might otherwise opt for other competitors such as the Freedom and Justice Party.

Above, Dr. Ghoneim’s face is once again displayed prominently to bring attention to the Revolution Continues Alliance, this time personally endorsing Mohamed Shabana. The slogan above Shabana’s name reads, “If you do not participate in change, you have no right to complain.”

“Feloul” Me Once

Of course, the Ghoneim-backed liberal campaign and the Muslim Brotherhood’s methodical electoral drive neglect one very significant Mansoura player: the feloul, or the remnants of the former ruling National Democratic Party (NDP).

As early as October, the April 6 Youth Movement began a national “black circle, white circle” campaign to help voters delineate as clearly as possible which candidates were tied to the former ruling party. The April 6 Movement of Mansoura even traveled to surrounding villages to distribute flyers and inform residents who the specific feloul candidates are in their respective districts. Back in Mansoura, April 6 continued to hold public gatherings to this same end. Below, a poster displayed at one such event lists the names of parties the movement believes to be under the control of feloul elements. The parties listed in the poster are the National Party of Egypt, the New Independents, the Egyptian Citizen, Democratic Peace, Modern Egypt, 11 February, Union, Freedom, and the Beginning.

Of the nine national parties listed above, five are actively campaigning in Mansoura: the National Party of Egypt, the New Independents Party, the Democratic Peace Party, the Union Party and the Freedom Party. The Freedom Party’s banner hangs below (“The Freedom Party: Freedom is a responsibility”):

Below, a group of youth show their disapproval by tearing down one such feloul banner hanging near the city’s main administrative building.

His Incumbency

Mansoura’s most prominent feloul candidate, Waheed Fouda, is not part of any such party list, but is instead campaigning for the individual candidacy worker seat as an independent. Fouda was the landslide winner of the highly corrupt 2010 parliamentary “contest,” and in a dizzyingly long list of individual candidates is perhaps the only contestant with near universal name-recognition among voters. Because of this latter feature, along with his vast network of local connections, many believe he remains unbeatable for the district’s mandated worker seat.

Pictured above, and to the left, is Waheed Fouda’s older brother, Mamduh Fouda, the former NDP representative and holder of the Mansoura’s “legislative throne” since the days of late President Anwar Al-Sadat. The above sign declares, “Oh, [Waheed] Fouda! Tell your brother the people of Mansoura love you.”

Above, in a narrow back alley in one of Mansoura’s more humble neighborhoods, a burst of Fouda campaign signs paint a trail to the candidate’s local campaign headquarters, a room that would otherwise park a single car.

Against the far wall of the office, a campaign sign belies an amateurish attempt to change “2010” to “2011” with the stroke of red ink so as to be reused for this year’s contest (see just above the candidate’s left shoulder).

The above sign reads: “The darling of the people of Mansoura. Ibrahim Muqbel supports and endorses the candidacy of Waheed Fouda.”

Fouda’s small town “headquarters” and campaign slogans attempt to drive home the “worker” candidate’s “man of the people” appeal. When not connecting with average voters from his humble office, however, Fouda can generally be reached at the gated Nile-side club owned by his older brother.

Zooming Out

The above, of course, only speaks to those who appear to be the largest and most visible players in the city as of late. A casual stroll down any Mansoura’s street will reveal a far more extensive panoply of faces, candidate symbols, and slogans than any single essay could capture. The classic liberal Al-Wafd Party’s forest green banners, for example, spy over most Mansoura’s streets beside a sea of seemingly faceless independents.

And the importance of banners should not be downplayed, as an official – or even commonly distributed – list of the district’s candidates has yet to be published as of late November. Street signs often remain the only way some players are able to inform voters on a wide scale that they are running in the district.

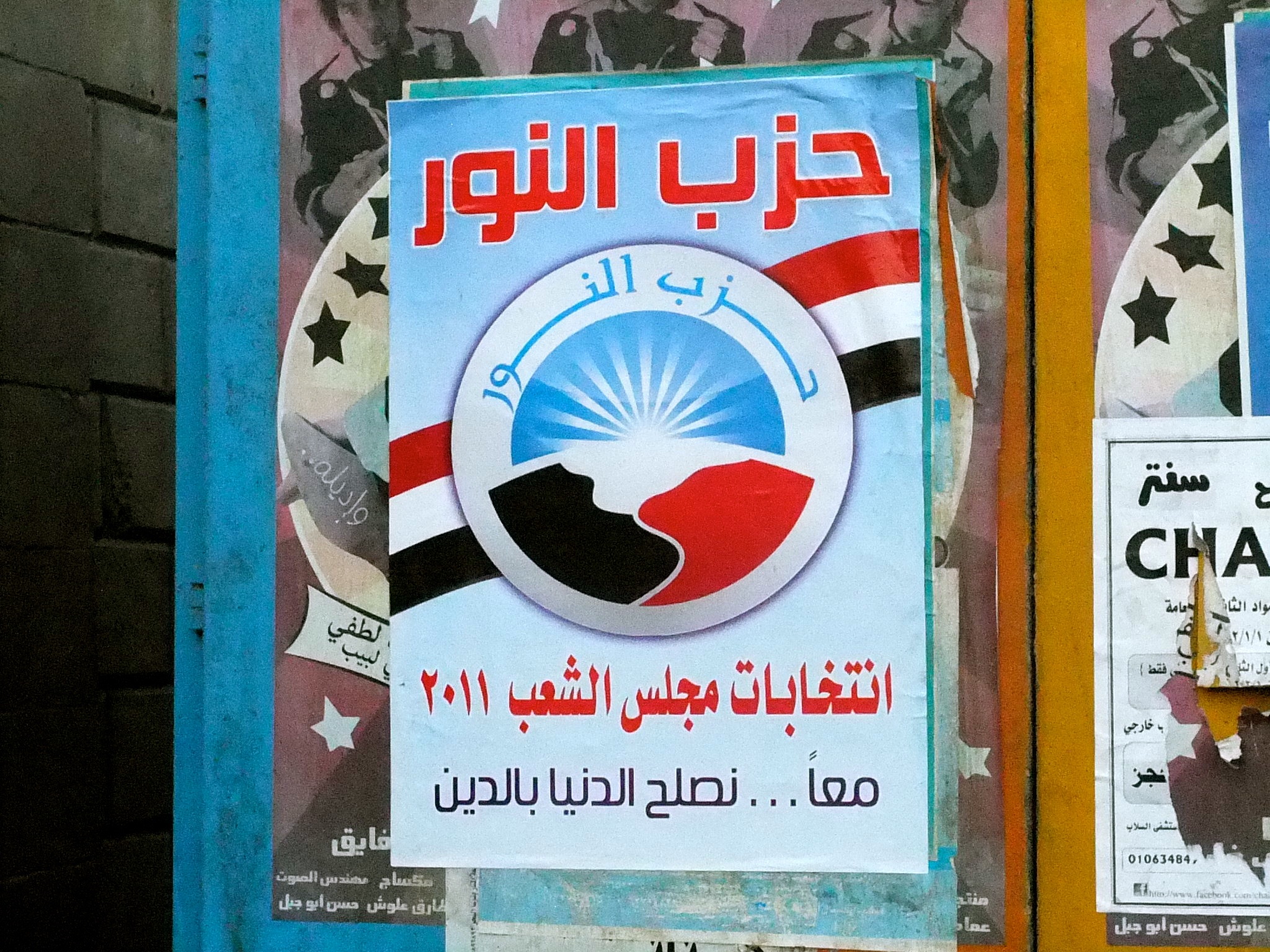

Finally, as first round election results have shown, it would be foolish to discount the ability of the more religiously conservative Salafist Al-Nour Party to take a sizeable minority of seats. As briefly alluded to in the introduction, party list candidates based in Mansoura must also compete over vast expanses of rural territory. Thus, although Al-Nour Party has run something of a quiet campaign in the city proper, this informs us little about their ability to garner any number of the district’s eight seats simply by outperforming their urban competitors in the city’s hinterland.

This poster, hanging in Mansoura in early November, reads, “Together we can reform the world through religion.” While this may count as an election violation on grounds that the use of religious symbols is illegal (see People’s Assembly Law), the party’s latest campaign iteration, photographed last week, toes a more innocuous line: “A political party working to progress the country.”

[1] Individual candidates must run as fe’at (professional) or umal (worker), or fellah (agricultural worker). A quota in place since the 1950s requires each individual-candidacy district to have at least one umal/fellah winner.