[This is a translation of a Jadaliyya article that was originally published in Arabic. Click here to access the Arabic version.]

Should the production of pasta, mineral water, butane gas cylinders, and gas station services qualify as classified military secrets? And does discussing these enterprises in public pass as a crime of high treason? The leaders of the Egyptian Armed Forces believe the answer is “yes.”

Until this very day, the role of the military establishment in the economy remains one of the major taboos in Egyptian politics. Over the past thirty years, the army has insisted on concealing information about its enormous interests in the economy and thereby keeping them out of reach of public transparency and accountability. The Egyptian Armed Forces owns a massive segment of Egypt’s economy—twenty-five to forty percent, according to some estimates. In charge of managing these enterprises are the army’s generals and colonels, notwithstanding the fact that they lack the relevant experience, training, or qualifications for this task.

The military’s economic interests encompass a diverse range of revenue-generating activities, including the selling and buying of real estate on behalf of the government, domestic cleaning services, running cafeterias, managing gas stations, farming livestock, producing food products, and manufacturing plastic table covers. All this information is readily available on the websites of relevant companies and factories, which publicly and proudly disclose that they belong to the army. Yet for some reason the military establishment insists on outlawing any public mention of these activities.

Why is the budget of the Egyptian army above public transparency and accountability? Is it because it is exclusively concerned with national defense and thus must remain classified? Not really.

It is certainly true that one part of the Egyptian army’s budget is concerned with defense-related activities, such as the procurement or co-production of weaponry. These activities, however, hardly have anything to do with the “classified” part of the army’s budget. As a matter of fact, information about many of these budgetary items is readily available in public records. That is because such items are mainly concerned with Egypt’s joint endeavors with a foreign partner that is legally obligated to disclose to its own citizens a full account of its activities, including military aid and arms deals (or co-production of military equipment) with countries like Egypt. This partner is, of course, the United States government, which grants the Egyptian army an annual 1.3 billion USD in aid through its Foreign Military Financing program. Reports on official US government websites, such as that of the Government Accountability Office, Department of State, Department of Defense, and Congress, provide data on US arms sales to Egypt and military equipment that the United States helped produce in Egyptian military factories.

The part of the military’s budget that is kept secret has little to do with national defense and more with the huge profits the army accrues from the production of non-military goods and services. In other words, these budgetary items have to do with: how many bags of pasta and bottled water were sold last month; how much money “Wataniyya”, the military’s gas station, generated last year; how many houses “Queen”, the military’s cleaning services company, attended to this month and how many nurseries the same company is in charge of running; how many truckloads of fresh beef have the military’s high-tech slaughterhouses in East Uwaynat sold this year; how many cabins they managed to rent out in the north coast Sidi Crir resort last summer; and how many apartments they sold in Kuliyyat al-Banat residential buildings and at what price? All these items together make up the “classified” part of the army’s budget, which the military establishment insistently keeps off the public record and out of the reach of parliamentary and public deliberation as well as oversight. Attempting to discuss the army’s so-called classified activities in public could result in military prosecution and trial, because these are, supposedly, “national security secrets” that Egypt’s rivals—like Israel—must not find out about.

This article examines the hidden role of the military in Egypt’s economy and how it tends to take on the form of economic activities for which the army is unfit and that steer the military establishment away from its principal obligations, namely advancing national defense and protecting the country’s borders. Of greater concern is how many of the army’s leaders have entered into networks of corruption and unlawful partnerships with private capital. The discussion that follows does not rely on classified sources, and is based on public information available in the news media, and the websites of the military-owned companies along with the job and marketing ads they publish.

["Queen: A pasta that carries its value," Image from unknown archive]

The army’s control over economy began in the aftermath of the 1952 revolution/coup, which paved the way for Egypt’s experience with state socialism under leadership of the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser. During this era, the state came to own all economic assets and means of production through nationalization programs. Austerity measures were adopted to limit consumption with the aim of enhancing the country’s economic independence. Egypt’s new ruling elite among army officers quickly installed themselves as the managers of state-owned enterprises—a task for which they were largely unqualified. “The people control all means of production,” according to the 1964 constitution, and Egypt’s military rulers in turn took the initiative to claim this control on behalf of the people. As corruption and mismanagement soon proliferated throughout the public sector, Nasser’s project ultimately failed to deliver the promise of economic prosperity. In some ways this failure was unsurprising given that officers, whose skills and knowledgebase were limited to military affairs and warfare, came to assume responsibilities such as managing the economy and the means of production—tasks for which they were unprepared.

In the 1970s, the army’s monopoly over power started to erode as late President Anwar al-Sadat decided to take Egypt off its socialist path, and reintroduced market economics as a means for fostering strategic and economic ties with the West. Sadat took steps to privatize parts of the state-owned sector, which military leaders tended to control, and pursued policies that gave Western consumer goods and services access to Egyptian markets. These policies came at the partial marginalization of military leaders, who now had to share influence with a rising community of crony capitalists, many of whom were close to Sadat and his family.

Fortunately for military leaders, however, this humiliating situation did not last for very long as the 1979 peace treaty with Israel came to the rescue of army leaders, helping them recover some of the influence they had lost under Sadat’s presidency. After ending the state of war with Israel, Egyptian leaders reasoned that laying-off thousands of well-trained army officers is politically undesirable. Thus, the state established an economic body known as the “National Services Projects Organization,” (NSPO) which founded different commercial enterprises run by retired generals and colonels. Through various subsidies and tax exemptions, the state granted military-owned enterprises privileges not enjoyed by any other company in the public or private sectors. The military’s enterprises were not accountable to any government body, and were above the laws and regulations applied to all other companies.

After 1992, when deposed President Hosni Mubarak began advancing full-fledged economic liberalization under US pressure—as proscribed by blueprints devised by the IMF and the World Bank—privatization programs steered clear of military-owned enterprises. Even when the Gamal Mubarak-controlled cabinet of businessmen accelerated privatization programs between 2004 and 2011, military-owned companies remained untouched. In fact, high-ranking army officers received their share of benefits from corruption-ridden privatization deals in the form of appointments to prestigious positions in recently privatized public sector enterprises.

Generally speaking, the Egyptian military establishment does not believe in US-style neoliberalism or free market policies, particularly those that would result in the army’s loss of its valued companies and assets. Such feared measures include limiting the state’s economic role, privatization, and promoting the role of private capital. For instance, in a 2008 Wikileaks cable, a former US ambassador to Egypt indicated that Filed Marshal Tantawi was critical of economic liberalization on the ground that it undermined the state’s control over the economy. Tantawi’s skepticism of neoliberal economics has little to do with his loyalty to the socialist model of the Soviet Union, where he received his training as a young officer. Rather, it is privatization’s potential encroachments against the vast economic empire owned by the military that Tantawi fears the most.

As managers, Egyptian army leaders usually run their enterprises in a traditional Soviet style inherited from the Cold War era. Yet as consumers, they tend to adopt a more “Americanized,” globalization-friendly orientation. There is no doubt that the ties between Egyptian military elites and their counterparts in the Pentagon play a role in fostering this “consumerist” orientation among Egypt’s military leaders. As part of defense cooperation programs between the two countries, many Egyptian officers travel on annual trips to the United States, getting exposed to a lifestyle that is radically different from the life of Soviet-style austerity through which they endured during the sixties and seventies. For instance, as he made his famous visit to Tahrir Square to meet with protesters during last winter’s eighteen-day uprising, Tantawi arrived in a fancy US-made jeep. Lieutenant General Sami Anan, prominent member of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), is known for his fondness for American consumer goods, according to a New York Times article. During his regular visits to Washington DC, Anan and his family are reported to shop for jeans, clothes, and electronics at Tysons Corner shopping mall in the suburbs of northern Virginia. In fact, American-style consumerism is rumored to be so prevalent among young army officers that many of them try to purchase their uniforms from American producers.

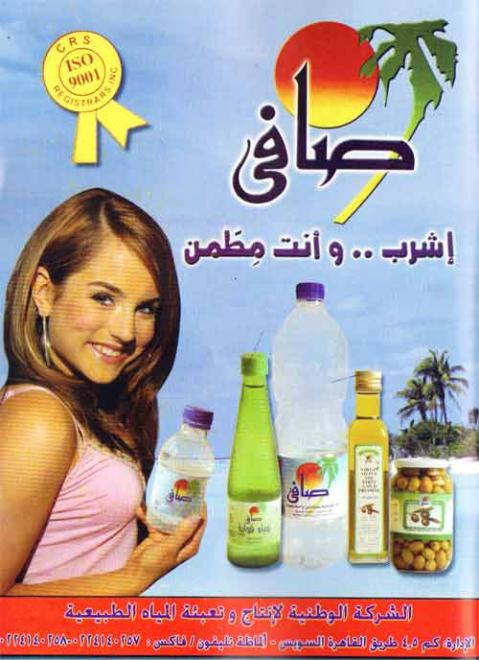

If military leaders were in fact fine administrators who are capable of advancing the country’s social and economic development, it would make sense for them to continue to maintain their economic interests and assets for the greater good of Egypt. But are they really capable of managing these enterprises? Once again, the answer is no. For example, very few of us have heard of “Queen,” the army-produced brand of pasta. Those of us who know it have never once described it as the best brand on the market. Nor does one ever hear that the army’s “Wataniyyah” gas stations offer services superior to those of other stations. Nor have we once heard anyone raving about “Safi” mineral water and how every dining table should have it. In reality, the army manages to sell its products not due to their superior quality, but rather through draconian practices. For example, the army effectively forces enlisted soldiers to spend their meager salaries on military-produced food products at army canteens in remote areas where non-military brands are not sold. In other cases, the army gets civilian distributors to sell its products by offering them ‘favors’ through underhanded deals.

Additionally, the military is heavily engaged in profiting from its control over vast amounts of land—thanks to a law that allows it to seize any public land for the purpose of “defending the nation.” In practice, military leaders use this law in order to use public lands for commercial investments, rather than the legally mandated purpose of national defense. An agency known as “The Armed Forces’ Land Projects” specializes—as its name suggests—in launching projects on lands controlled by the Armed Forces. Properties owned by this agency include lands in Nasr City on which residential units are currently being constructed. In the northern coast, the military is using its seized lands to build tourist resorts and hotels, as it has done in Sidi Crir. Recent newspaper advertisements indicate that the Armed Forces are currently engaged in the commercial sale of lands in the northern coast for the purpose of building tourist resorts and residences.

Furthermore, as the managers of a state-owned economic empire built on corruption and oppression of working classes, military leaders have become decisively complicit in repressing labor and violating their rights.

Being an army general, a member of the National Democratic Party (NDP), and a Member of Parliament for ten years almost guarantees that one is part of a corruption network. General Sayed Mishaal perfectly fits this profile. Before becoming Minister of Military Production, Mishaal was a director of the National Service Projects Organization (NSPO). During that time, he was also a member of the NDP, and as an MP for Cairo’s district of Helwan for three consecutive terms from 2000 to 2011. He used to proudly brag about managing to name the military-produced bottled mineral water Safi after his daughter. Mishaal was removed from his post after the revolution as a result of referrals to the General Prosecutor accusing him of wasteful spending of the ministry’s funds. Mishaal’s victory in parliamentary elections in Helwan was made easy by the fact that he could mobilize the votes of tens of thousands of individuals who work at “Military Factory 99,” located in the district. Mishaal used to show up at the factory to celebrate and make merry with the workers during election campaign events, only to disappear and hardly return after his victory.

["Safi: Drink it while you are assured", Image from unknown archive]

The name “Military Factory 99” has also become associated with the repression of workers, especially that labor-employer relations in the factory are not subject to traditional union or government regulations. In August of 2010, Factory 99’s workers broke out into intense protests after one of their colleagues died as a result of an explosion. The director of the factory, who was also a general, had brought in a number of gas cylinders in order to test them out, even though the workers were not trained to use them. When several cylinders exploded, he told the workers that it would not matter if one or two of them died. Then, when one of them did in fact die, they stormed his office, gave him a beating, and then staged a sit-in. Subsequently, the workers’ leaders were tried in military courts for charges of revealing “war secrets” on account that they spoke publicly about butane gas cylinders.

This in turn leads us to the issue of the repressive treatment of workers on military-owned livestock farms. These workers are usually poor conscripts who end up laboring without pay. The typical story goes as follows. A soldier who hails from rural areas or poor cities is conscripted (supposedly) to learn to recite patriotic slogans and songs during morning assemblies and marches. He then forgets about all these, along with his own dignity, as he finds himself laboring with no pay in one of the military’s livestock farms, which usually extend over hundreds of thousands of acres. As he collects eggs and tends to livestock and chickens, he endures humiliation and subjugation at the hands of his supervising officers. There, he loses any feeling of national dignity, which the army allegedly seeks to instill in him. Should any war ever break out, his performance in the battlefield would be shockingly horrid, having not received any training in combat skills—thanks to the leaders who have recruited him and assigned him his post.

The military establishment’s propagandists often argue through state controlled media outlets that the secrecy of the Armed Forces’ budget is a patriotic duty that we must honor and protect as Egyptians. It is hardly convincing, however, that those conscripts who are carrying out force labor at the NSPO agree with that statement. In fact, given their conditions, they may not even grasp the concept of “patriotism” to begin with.

Any discussion of the relationship between the army and economy cannot ignore the military establishment’s near-absolute dominance of the local economy in various Egyptian governorates. It is well known to many that Egyptians outside of Cairo live under virtual military rule, wherein twenty-one of the twenty-nine appointed governors are retired army generals. This is in addition to dozens of posts in city and local governments that are reserved for retired officers. These individuals are responsible for managing wide-ranging economic sectors in each governorate. In other words, army generals—whose expertise does not go beyond operating armored tanks or fighter jets—are suddenly tasked with managing and overseeing significant economic activities, such as the critical tourism sectors of Luxor and Aswan, Qena’s sugar manufacturing enterprises, or Suez’s fishing and tucking industries.

There is no shortage of corruption stories involving army generals and their mismanagement of local economies. For example, in one such incident former Luxor Governor General Samir Farag—who previously served as director of morale affairs of the Armed Forces—sold land to a local businessman below market prices. The land was initially designated for building an Olympic games stadium. In fact, after hundreds of millions of Egyptian pounds were spent on the project, all of a sudden construction was suspended and all the spent funds went to waste, as the land was sold to a businessman that owned a hotel across the street. Similarly, the residents of Aswan allege that their governor General Mustafa al-Sayed was involved in corruption cases involving public lands and the tourism sector. Al-Sayed recently appointed at least ten retired army brigadier generals as managers of the quarries and river ports and offered them exorbitant salaries, even though they lack relevant qualifications and experience.

Given that those in charge of managing our local economies receive such jobs as a “retirement bonus,” it is unsurprising that local development throughout Egyptian governorates has remained stagnant for decades and lags behind other countries.

It is for the sake of all the aforementioned interests and privileges that military leaders killed unarmed revolutionaries (and continue to do so) in Tahrir, Abbassiya, Maspero, Mohamed Mahmoud, and Qasr Al-Ayni.

Completing the revolution and the triumph of Egyptian demonstrators would inaugurate a genuine democratic transformation in this country. It means full financial transparency and subjecting all budgets to the principle of accountability. Completing the revolution means the army must lose its institutional economic privileges, as military leaders return to their original role, namely national defense—and not the management of wedding halls.

![[Members of Egypt’s armed forces display canned tomatoes, roasted onions, and other foods that the military factories manufacture. Image by David Degner.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/20111031_EgyptFlag_00058.jpg)

![Teaching Palestine Today: On the [F]Utility of International Law](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/63x63xo/bruh250421081905840~.png)