Gönül Dönmez-Colin, Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance, and Belonging. London: Reaktion Books and Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Asuman Suner, New Turkish Cinema: Belonging, Identity, and Memory. London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2010.

Deniz Bayrakdar, Aslı Kotaman, and Ahu Samav Uğursoy, editors, Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and the New Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009.

Upon being awarded the Best Director honor at Cannes in 2008 for his film Üç Maymun [Three Monkeys]—becoming the first Turkish director to receive this award—Nuri Bilge Ceylan declared that he wanted to dedicate the award “To my lonely and beautiful country, which I love passionately.” Ceylan’s words are very much in keeping with the melancholy quality of his films themselves: one thinks of the protagonist of his previous film, İklimler [Climates], played by Ceylan himself, a solitary figure wandering through the almost unimaginable mountainous beauty of Ağrı, in the snowy eastern province of Turkey, or the two heroes of his 2002 film Uzak [Distant], who take turns staring out across the Bosphorus, shot by Ceylan to maximize its almost painful loveliness. (I have not yet had the chance to see Ceylan’s latest film, Bir Zamanlar Anadolu`da [Once Upon a Time in Anatolia], reviewed here, which was recently honored at Cannes, but it is clearly a continuation of his melancholic project.) But what exactly is this “loneliness” of Turkey that Ceylan wished to share with that audience in Cannes?

[Still image from Nuri Bilge Ceylan`s İklimler (Climates)]

A full answer to this question would have to consider the particular nature of Turkish national identity, located in the most literal sense between East and West, bridging Asia and Europe. In the much more narrow terms of literary and cultural studies, the particularity of Turkey, and of Turkish literature, film, and culture, has sometimes caused it to be marginalized, in part because it does not fit any of the existing paradigms: not part of the traditional sense of “European” culture, but also not able to fit into a new category such as postcolonial culture. If it was to be found anywhere, it would be within the category of Middle Eastern culture, but even here, the fit has hardly been a comfortable one.

In terms of the cinema of Turkey (I follow Asuman Suner in using the designation “the cinema of Turkey” rather than “Turkish cinema,” since the former phrase “places the emphasis not so much on ‘Turkishness’ as ethnic identity, but on Turkey as a geopolitical entity and a locus of divergent ethnic, religious, and cultural identities”), this problematic takes on a very particular form. Until the past decade, there were almost no Turkish auteurs receiving international attention. Occasionally, an individual film would receive international acclaim—Metin Erksan’s Susuz Yaz [Dry Summer] won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 1964, and Yılmaz Güney’s masterpiece Yol [The Way] shared the Palme d’Or 1982—but by and large, in spite of a large body of strong work (particularly work influenced by the social realist and neo-realist traditions), the cinema of Turkey has generally not figured on the map of international cinema, neither acknowledged as part of the European artistic tradition nor recognized in the way that the various national cinemas that have contributed to the “Third Cinema” tradition have. At the same time, while it has boasted a large and influential popular film industry since the 1950s, Turkey’s Yeşilçam (the industry’s nickname, which comes from a street in the Beyoğlu section of Istanbul that was the heart of the film industry) has also not received much international attention, in part because, despite its size, it never achieved the sort of regional influence that the industries of India or Egypt achieved through the dissemination of films outside their national borders. For all these reasons, cinema studies, particularly cinema studies in English, has by and large produced very little work dealing with the cinema of Turkey.

This attitude may be beginning to change. The work of contemporary filmmakers such as Ceylan, Zeki Demirkubuz, Yeşim Ustaoğlu, and Semih Kaplanoğlu, not to mention the growing reputation of the Turkish German director Fatih Akın, has caught the attention of cineastes. Meanwhile, the popular film industry in Turkey, which had suffered a period of decline in the 1980s and 1990s, has grown much stronger in recent years, and the growing Turkish communities in Europe and the United States has meant that Turkish popular films have begun to find a wider audience outside Turkey. This moment might allow us, not just to consider the current cinema of Turkey, but also to take the opportunity to revisit the full history of a national cinema that has not as yet received the international attention that it deserves. The three books under consideration in this two-part review essay—Gönül Dönmez-Colin’s Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance, and Belonging (considered here), Asuman Suner’s New Turkish Cinema: Belonging, Identity, and Memory, and the edited collection Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and the New Europe (both of which will be considered in part two of this review)—taken together, do an admirable job of laying the cornerstone for a new generation of work in English on the cinema of Turkey.

In her introduction to Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance, and Belonging, Gönül Dönmez-Colin notes that “Scholarship on Turkish cinema is rather new and the sources available in languages other than Turkish are limited”; she cites this general lack of scholarship as her “motivation in venturing into a study of a film industry that offers challenges in its diversity, originality, and uniqueness.” Dönmez-Colin comes to this challenge having written two previous books on film from the Middle East and Central Asia and having edited the collection The Cinemas of North Africa and the Middle East. In Turkish Cinema, she displays an encyclopedic knowledge of the cinema of Turkey from its inception in the early years of the twentieth century to its twenty-first century developments. While it is not without its weaknesses, Turkish Cinema is precisely the sort of book that could help to anchor the developing field of Turkish cinema studies in English.

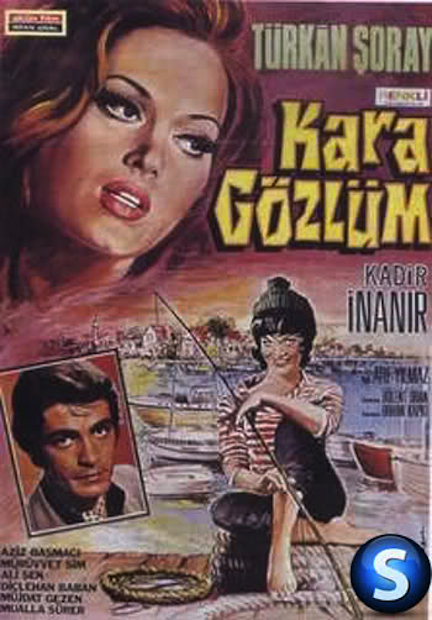

Dönmez-Colin frames the book around the themes of identity, distance, and belonging (although, I would argue, one of the book’s strengths is that it does not force its analysis of the films she discusses into any sort of tight coherence around these three themes), and she returns repeatedly to a sense of the dissonance to be found in Turkish identity itself. She opens with an example from a classic and hugely popular film from 1970, Atıf Yılmaz’s Kara Gözlüm [My Dark-Eyed One], starring Türkan Şoray, “the sultana of Turkish cinema” (to use Dönmez-Colin`s phrase). The film follows a familiar “star is born” narrative, with Şoray playing the daughter of a fisherman who becomes a famous singer. To prepare her for her new life, she is—in a scenario repeated again and again in Turkish popular culture—assigned to learn from a teacher of etiquette, setting up the inevitable conflict between her old “à la turca” lifestyle and the new “à la franca” culture represented by “Madame” in her cultural lessons.

[Publicity poster for Kara Gözlüm (My Dark-Eyed One). Image via Google Images.]

Dönmez-Colin finds in this oft-repeated scenario a representation of the “polarity of identities” that continues to affect Turkish cultural identity to this day, the polarity between East and West and, more recently, between religious and secular identities. Implicit here as well is the literal, geographical split in the city of Istanbul itself, between the “European” side and the “Anatolian” side (represented nicely, in Dönmez-Colin’s book, by a still from Ceylan’s film Uzak, in which, as Dönmez-Colin’s caption puts it, “the disillusioned artist/intellectual has a moment of reflection on a bench facing the Anatolian coast and perhaps begins to see the point of view of the provincial, his suppressed ‘other’”). Indeed, one of the striking points about the cinema of Turkey is that it often reflects some of the themes and styles found in what Hamid Naficy has called “exilic cinema” (Naficy’s work is a point of reference for both Dönmez-Colin and Suner), but the “distance” represented in films such as Ceylan’s Uzak is reflective not of the sense of displacement found through literal exile outside the boundaries of the nation, but rather of a pervasive displacement within Turkish society (and, indeed, even within the city of Istanbul) itself.

Rather than taking an auteurist approach and focusing on specific filmmakers (with the exception of a chapter dedicated to the work of Yılmaz Güney—although, even in this chapter, Dönmez-Colin seems more interested in viewing Güney’s films as symptoms of their historical moment rather than as examples of the interconnected body of work of an auteur), Dönmez-Colin divides the book into a series of thematic chapters, organized around interlocking themes: “In Search of Identity”; “Migration, Dis/Misplacement and Exile”; “Denied Identities”; “Gender, Sexuality and Morals in Transition”; and “A Modern Identity or Identity in a Modern World.” As the chapter titles suggest, Dönmez-Colin’s interest is in large themes, and each chapter moves through several decades in tracing these themes.

Indeed, the first chapter traces the history of the cinema of Turkey back to its origins before the founding of the Turkish Republic. Her fascinating (if brief) overview of these early origins provides, in miniature, some of the social and political themes that will recur throughout the book, including the government’s involvement with the film industry. For example, Dönmez-Colin suggests that a documentary called Ayastefanos`taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı [The Demolition of the Russian Monument at St. Stephan], shot by Fuat Uzkınay, an Ottoman army officer, in 1914 and considered as the first national film according to the official history of Turkish cinema (although there are no surviving copies of the film, and some researchers have questioned whether its existence is anything more than a myth), was made as part of a series of propaganda events “organized by the Union and Progress Committee to improve public opinion.” The first official cinema institutions were placed under the control of the army, and the shooting of the first feature film, Himmet Ağanın İzdivacı [The Marriage of Himmet Ağa] (1918), was suspended when most of the cast and crew were recruited to serve in the Dardanelles. Once shooting was resumed, the film’s Romanian director, Sigmund Weinberg, was replaced by Uzkınay after war broke out between Romania and the Ottoman Empire. This early history, Dönmez-Colin argues, was central in “establishing a solid relationship between the army and cinema, which has manifested itself overtly or covertly over the decades.” It also reveals a deep interpenetration between cinema and state politics in the very origins of Turkish cinema.

These early years were followed, during the first two decades of the Republic, by a period dominated by films made by theater directors, in particular Muhsin Ertuğrul, who made the first sound film in Turkish cinema and was also the first Turkish director to receive international acclaim, winning an award at the Venice Film Festival in 1934. Dönmez-Colin likens the hegemony of Ertuğrul during this “Period of the Theater Men” to “the one-party system of the early years of the Republic”; similarly, she suggests that the next cinematic era, “The Period of Transition,” “was a transition period for Turkish politics as well.” The guiding event that she uses to mark the third period in the cinema of Turkey, the rise of the Yeşilçam film industry, is in turn linked to the ascendance to power of the Democrat Party in 1950, since the DP advocated a form of populism that was reflected in classic Yeşilçam films by directors such as Lütfi Ö. Akad, Atıf Yılmaz, Metin Erksan, and Memduh Ün. The 1960s signal the next phase in Dönmez-Colin account, with the emergence of “a new kind of cinema…influenced by social and political changes in the country,” particularly the military coup of 1960. The ouster of the Democrat Party and the establishment of a progressive constitution, in Dönmez-Colin’s account, ushered in a more relaxed atmosphere, reflected in films that experimented with social realism, including Erksan’s Susuz Yaz [A Dry Summer], Güney’s widely-praised first film At, Avrat, Silah [Horse, Woman, Gun] (1966), and Akad’s Hudutlarin Kanunu [The Law of the Borders] (1966), co-written by and starring Güney, which eventually received wide international acclaim. However, in a sign of things to come, Hudutlarin Kanunu was banned by Turkish censors and prevented from participation in foreign festivals.

[Still image from Hudutlarin Kanunu (The Law of the Borders)]

For Dönmez-Colin, the high point of this period of social realist filmmaking, 1960 to 1965, “reflected the search for identity in a period of rapid transition from traditionalism to modernism.” She sees the period that follows as marked by a split between directors like Halit Refiğ, who saw Yeşilçam as the true national cinema and advocated a rejection of Western avant-garde forms, and advocates of the “New Cinema,” who hoped to introduce modes borrowed from European art cinema into the cinema of Turkey. The films of Yılmaz Güney were rare exceptions that managed to bridge this split—his work, such as the 1970 film Umut [Hope], managed to achieve commercial success and was also revered by the New Cinema group—but his career was decimated by political repression and cut short by his untimely death in 1984.

There followed a period of general decline; while directors influenced by Güney continued to draw praise from international audiences, the late 1970s are generally seen as the end of the Yeşilçam era, as the industry succumbed to the loss of audience occasioned by the arrival of television and the flooding of the market by Hollywood films. The coup of 1980 put a close to this phase; what followed, according to Dönmez-Colin, was “another crisis of identity in Turkish cinema.” The split that emerged from this moment of cultural and political crisis was similar to the one that marked the previous era—between those, like Şerif Gören and Sinan Çetin, who argued for a robust popular national cinema, albeit one that followed the box-office formulas perfected by Hollywood, and those, like Ceylan, Zeki Demirkubuz, Yeşim Ustaoğlu, and Semih Kaplanoğlu, associated with the “New Turkish Cinema” (or the “New New Cinema,” as some called it) and its art house tradition—although the contemporary contestation lacks something of the politically-charged nature of the debates of the 1960s and 1970s. “Corresponding to the geopolitics of the country,” Dönmez-Colin concludes, falling (as she occasionally does) into the realm of the cliché, “Turkish cinema has turned its head towards the West while its feet are grounded on the soil of the East.”

Dönmez-Colin manages to make her way through this history in approximately fifty pages. As this suggests, her strength, as a critic, is in painting with a broad brush, which makes Turkish Cinema an ideal book for readers looking for an overview of the cinema of Turkey. Particularly excellent is her chapter “Gender, Sexuality, and Morals in Transition,” where she moves through literally decades worth of films, tracing the changes (and lack thereof) in the representation of women. One particularly admirable aspect of this chapter is that it manages to suggest the powerful performances and pervasive cultural influence of iconic actresses such as Şoray, Fatma Girik, and Müjde Ar, while at the same time not ignoring how the films in which they appeared helped to perpetuate a patriarchal viewpoint. Dönmez-Colin also includes an interesting analysis of the portrayal of same-sex desire in Turkish cinema, beginning with several films of the 1960s that included scenes of lesbian desire, and focusing on the contemporary work of the filmmaker and video artist Kutluğ Ataman. Dönmez-Colin’s chapter on Yılmaz Güney, who she clearly admires both for his films and for his political example, is informative and quite moving, and her analysis of the representation of suppressed cultural and political issues in Yeşim Ustaoğlu’s films Güneşe Yolculuk [Journey to the Sun] (1999) and Bulutları Beklerken [Waiting for the Clouds] (2004) is also quite strong.

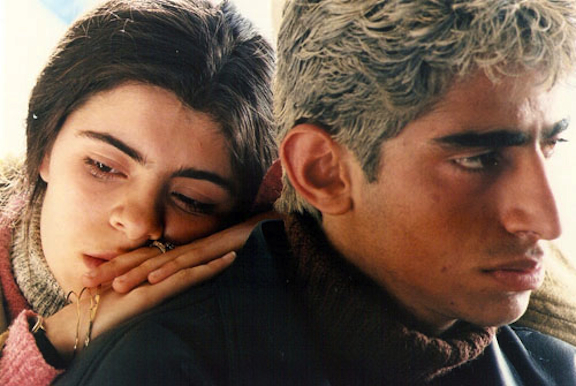

[Still image from Güneşe Yolculuk (Journey to the Sun)]

Dönmez-Colin’s weakness, however, is as a reader of individual films. Given her large-canvas approach, this is perhaps an inevitable problem for a book such as Turkish Cinema. Individual films often come up more as examples of larger trends or themes than as cinematic texts to be analyzed in and of themselves; given the sheer number of films that she writes about, her attention to particular films sometimes goes no further than a general overview or plot summary. Issues of form and style seem not to be of much interest, except as they might be analyzed as reflections of larger social realities or as indicators of a film’s belonging to a particular “stage” in the development of Turkish cinema. When she is addressing filmmakers whose work she clearly admires—Güney, Ustaoğlu, and Ataman appear to be particular favorites—she will stop to linger over stylistic details and narrative nuances. With other filmmakers, she has less patience, and she can be downright dismissive when addressing the films of filmmakers such as Ceylan and Demirkubuz (although in fairness she spends a significant amount of space on both of them). This unevenness appears to reflect more on her own preferences than on the significance (or lack thereof) of particular filmmakers to the narrative of Turkish cinema that she presents. This is not a complaint in and of itself; indeed, it is rather refreshing to see a book such as this one that is so stamped by the author’s individual preferences, and it reveals her to be a critic with a passion for cinema. It does mean, however, that certain readers may come away disappointed with the treatment accorded to particular films and filmmakers (since I am a great admirer of the films of Ceylan and Demirkubuz, I would include myself in this category). However, Dönmez-Colin encyclopedic knowledge of Turkish cinema and her apt encapsulation of large swathes of cultural history help to make up for these shortcomings.

[Part two of this review essay, which focuses on Asuman Suner’s New Turkish Cinema: Belonging, Identity, and Memory and the edited collection Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and the New Europe, can be found here.]