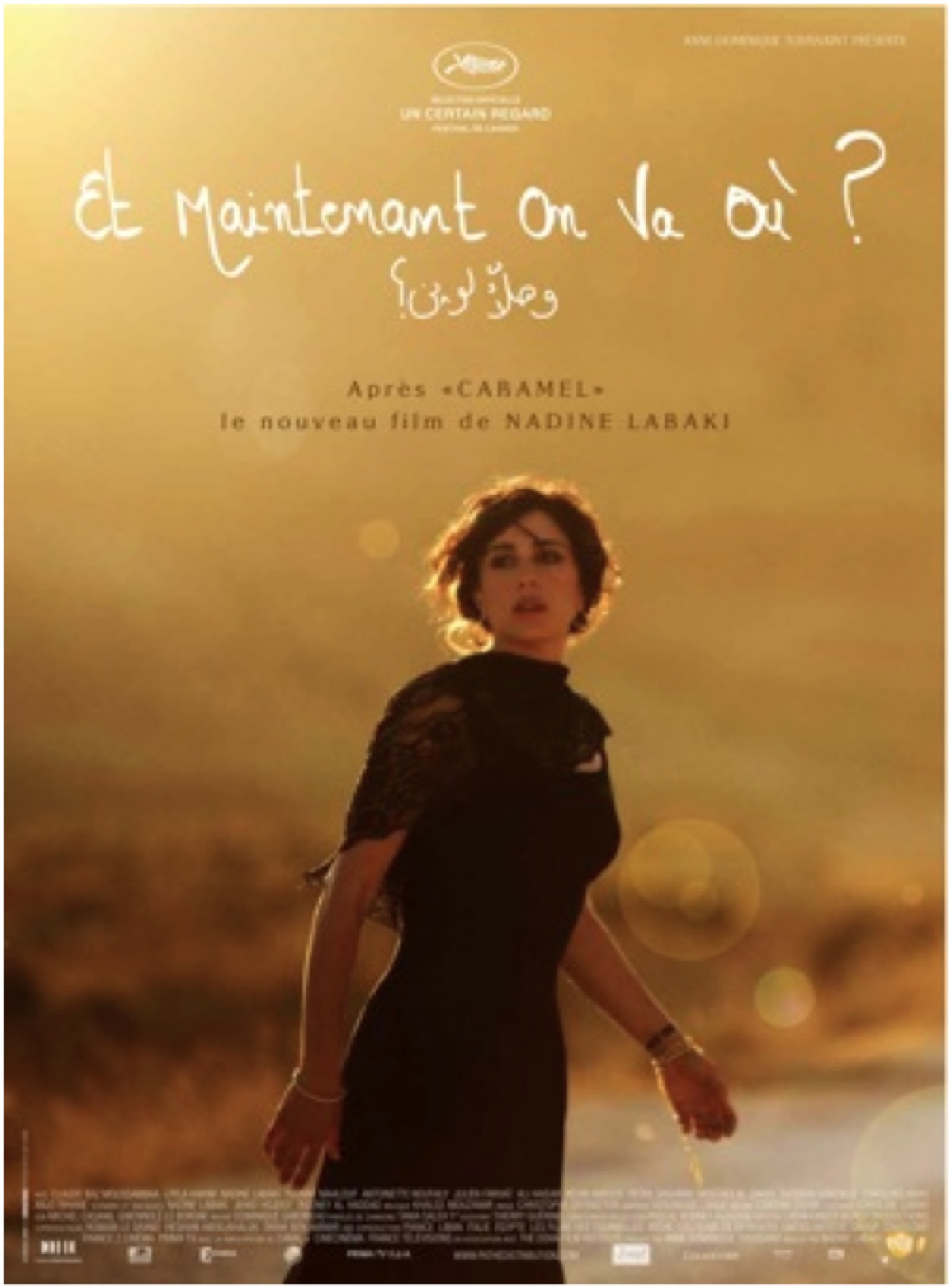

Where Do We Go Now? Directed by Nadine Labaki. Lebanon/France, 2011.

There is a heartbreaking scene towards the end of Wa-hala’ li-wayn (Et maintenant on va où? Where do we go now?), the second feature film from Lebanese writer, producer and director Nadine Labaki. A teenaged Muslim boy named Hammoudi (Mostafa Al Sakka) who has playfully stolen a cap from his Christian neighbor, Nassim (Kevin Abboud), gets marched over by his mother Afaf (Layla Hakim) to Nassim’s house in order to return it. Hammoudi thinks Nassim is sick inside his room, unable to move or even to speak, so he makes a heartfelt apology through the door. He says he is sorry for picking on him, for stealing his cap, and he hopes that all the sectarian troubles that have been flaring up in the village will blow over soon. What the audience knows but Hammoudi does not is that Nassim has recently been killed, caught in a crossfire of sectarian fighting elsewhere in the country. The audience also knows that Nassim’s mother Takla (Claude Baz Moussawbaa) has secretly buried him in the village well in order to prevent the pox of sectarian violence from spreading through the village. To call this staging of Hammoudi’s apology “loaded” would be an understatement. His words of remorse are ones that can never be rejected nor accepted—and in the film this apology comes to stand as a poignant metaphor for the structural obstacles to reconciliation and justice in a “never-quite postwar” Lebanon. The coherence of the film relies on the notion that a mother might actually go to such devastating lengths to “protect” her village from further bloodshed, but ultimately the film is worth the effort of bracketing questions about the plausibility of her act.

Where Do we Go Now? is a kind of fractured Lebanese fairy tale, set in an unnamed mountain village that has known both sectarian warfare and periods of inter-sectarian harmony. We see a mosque and a church situated neatly side by side, and an imam and a priest who are friends. Though separated, the Muslim and Christian cemeteries are on adjacent plots of land, their tenants peaceful neighbors to one another. We are, in other words, squarely in the realm of national allegory in this film, and although Labaki has stated in interviews that the story is meant to speak to broader universal themes, in many ways the film asks us to imagine that the village is Lebanon itself. The plot is relatively straightforward, pitting the wiles of peace-loving women against the sexual drives of war-mongering men. As sectarian tensions mount, the women of the village devise increasingly outlandish schemes to prevent war from breaking out—and it is all very good fun.

Labaki returns to some of the themes raised in Sukkar al-Banāt (Caramel), her debut film, which delighted audiences with a wry and realistic account of a Beirut beauty salon that functioned as both microcosm and melting pot, where family, gender and sexuality were discussed in universal terms, without directly confronting the specific political and ideological rifts within Lebanese society. Where Do We Go Now? has a similarly universal appeal, but has a far more ambitious political agenda. It was screened at Cannes in May, won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival in September, and hopefully will be distributed in the U.S as soon and as widely as possible, as it has been acquired by Sony Pictures Classics.

Directed, co-written and co-produced by Labaki, the French distributor Pathé International describes the film as a “heart-warming tale” of “women’s unwavering friendship [that] transcends, against all the odds, the religious fault lines which crisscross their society” with “women’s ingenuity” and “sass” mobilized “in order to prevent bloodshed and turmoil.”

In the opening scene, women of all religious affiliations stylishly dressed in black perform a morbid yet sensual dance on their way to the cemeteries in order to clean up the graves and lay a few new flowers. The protagonist Amal (Nadine Labaki) is a young Christian woman, somehow unattached to any family or family responsibilities (we never discover where or how she lives exactly), who is in the process of renovating a café in the town center. One sees black and white photographs in the café, in people’s homes, and in the cemeteries that display the faces of young men who were killed in the last round of fighting. Amal also sits on a kind of informal village council comprised entirely of women, of all ages and sectarian affiliations, which meets, apparently, to chat, to sew wedding dresses and to eat chocolate; in time, we come to understand that this council of wily women is the most important social institution in the village, serving as the moral and ideological police force for the community.

As the scruffy and attractive young Muslim handyman, Rabih (Julian Farhat), spruces up Amal’s place, the two occasionally gaze longingly at one another. In an early scene, they sway together in a shared fantasy song-and-dance. Such musical interludes punctuate the movie throughout, providing moments of escape and alternative possibility. At the outset, the only two characters who have a regular connection to the outside world, which they can only reach by crossing a zigzagging mountain bridge that is rigged with land mines, Roukoz (Ali Haidar) and Nassim, climb to the top of a hill in order to get a signal on an old portable cassette player (ghetto blaster) through which they run a cable down to the café so that everyone can hear the voice of Fairouz. When the news broadcast interrupts with reports of sectarian fighting, Amal nervously changes the channel. Later they set up a TV set in the village square, where the village people gather in order to watch together, or, as the Mayor (Khalil Bou Khalil) puts it, to collectively move from the twentieth into the twenty-first century! The mayor, a Christian, also hopes to soon re-open the road connecting the village to the rest of the world. The first scene they see on screen is the weather report given by a scantily clad woman (à la LBC, the Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation), intimating how hot it is about to get.

On another evening, the village is out to watch an old movie on TV, and it is in this scene that the real plot of the movie begins. When that movie becomes too risqué, Yvonne (Yvonne Maalouf), the mayor’s wife, insists that they change the channel because there are children around. They settle on a news broadcast, which reports the same sectarian clashes that some have heard on the radio. In response, the crowd suddenly grows irritated and anxious. At first, they argue about things that are banal and personal. But soon, their words become sharper, and their targets larger. The next day, when Roukoz and Nassim return with newspapers that report on the sectarian tension, the council of women decides to incinerate them. Soon after, they resolve to cut the television cable and to destroy the loudspeakers. Consequently, Nassim tries to borrow a replacement speaker from above the church altar. When he falls from the ladder, he cracks the giant wooden cross in two. And then the plot explodes, as Christians assume that the cross was deliberately destroyed as an affront. Thus ensues a series of tit-for-tat reprisals and escalating sectarian tensions in the village.

The council of women are pushed to take dramatic action in order to quell the growing unrest. Indeed, it often seems that the more the women try to tamp down on the men’s sectarian proclivities, the more violent those men become. Lest it be perceived that religion as such is their enemy, however, both the imam and the priest are brought in to conspire with them in their quest to preserve social harmony. Eventually, the desperate council of women are driven to hire a group of Russian exotic dancers after seeing an advertisement for their “Super Night Club.” The Russians arrive in town like a big burlesque show. They wear few clothes and speak a hybrid of Russian and English. The way they strut around delights the men and amuses the women. In one of the most ridiculous scenes, all the men in town—from the youngest of boys to the oldest of sheikhs—work together under the burning sun to dig an improvised swimming pool so that their guests can tan themselves properly.

The plot takes its most tragic and volatile turn when Roukoz returns to the village one day with Nassim’s body on the back of his motorcycle. Roukoz is distraught, and his mother is destroyed, but she knows if any Christians hear of what happened the entire community will immediately seek to take revenge, and the village will slide straight back to the bad old days. So she washes her son’s corpse and buries him in the village well. When her older son Issam comes home in search of a gun, furious over the rapidly escalating feud, his mother shoots him in the ankle to prevent him from going out. “I’m not going to lose you, too,” she mutters.

So the Russian women dazzle the men, temporarily, but even they fail to adequately quench the men’s thirst for sectarian bloodshed. Indeed, after the gunshot injuring Issam is heard around the village, their sleazy pimp comes to tell them that they should get out of there. The Russian women respond that they are not scared and that the village people can go ahead and kill each other for all they care. The women continue smoking their ample hash and playing cards. The point of this scene is compelling, since it seems to be chastising the Lebanese for allowing foreigners to cavort like this in their country even as the Lebanese savage each other. At another point, the Russian women visit the cemeteries, and one of them comments, “There are more dead people than living here.” They see a photo of Yvonne’s son that they recognize from her house, and remark how they can now understand why she is so crazy. “Poor mothers,” they intone. (In the closing frame of the film, the work is indeed dedicated to “our mothers.”) Another Russian replies, “They are even buried separately.” This, it seems to me, is one of the only moments in which the everyday practice of sectarianism, which might be opposed to the innate passion for one’s community against all others, is referenced. Indeed, it should be pointed out that sectarianism is not only a sense of primordial loyalty to one’s family, clan or sect; it is also a cultivated sensibility, an ensemble of social, cultural and even funerary practices that undergird those individual and collective identities. But this moment of potential critique in the film seems to only ever get translated into a kind of feel-good liberal conscience, which suggests that we all need to “co-exist” and “tolerate” one another. Such bromides do not necessarily undermine “really existing” sectarianism, and can, moreover, re-inscribe sectarian boundaries in surprising ways. The essentialism of sectarian identities is most fully accomplished, though, in the final work of magic concocted by the council of women.

They decide to call a “dialogue session,” in which the men are expected to air their grievances and to come to some sort of an agreement. In preparation, all of the women get together for a rollicking song and dance routine in which they spike all kinds of baked goods—cakes, cookies, manʿusheh—with enough hashish to tranquilize a menagerie of charismatic megafauna. The results are predictably hilarious, as men start slapping each other on the back and confessing their undying love and respect for one another and for the intercommunal harmony of the village. They are stoned out of their minds, and can hardly believe their eyes with the pièce de resistance, as the gold-hearted Russian prostitutes appear, decked out in extravagant Oriental regalia. The revue they perform soon becomes a debauched dance party.

As the village turns into a Super Night Club, the women disappear to collect and bury all the village’s weapons out in the fields. But they have an even more devious trick in store. When the men awake the next day, groggy and hung over, each one finds his wife and family having flipped their sectarian affiliation. So, the mayor awakens to find Islamic injunctions and artwork adorning his wall, and his wife is prostrate in the living room, fully veiled, praying. Confused, he asks her, “What are you doing, yoga?” Meanwhile, Hammoudi is awoken to his mother sprinkling him with holy water and wafting incense over his bed. This is all a funny bit, and demonstrates the women’s willingness to put their bodies on the line in the sake of inter-sectarian harmony and “tolerance,” as more than one tells her husband, “I’m one of them now,” as a means of preventing him from taking any kind of revenge on the other community. The message is that love—or the matrimonial love of husbands for their wives—can overcome sectarian prejudice.

There are, it goes without saying, some problematic ideological dimensions of the film. In essence, the question Labaki poses is a very old one: Wouldn’t the world be a more peaceful place if it were run by women? Yet gender and sexual identity are arguably more fluid in reality than those representations that are on display in Labaki’s film. Indeed, gender difference gets represented as primordial, even biological. Men are from Mars and women are from Venus; men are sexualized sectarian animals, while women are agents of pacifism, who bear the brunt of those uncontrollable passions and work to set things right again after men have made a mess of things. The plot turns on women being at once both powerful and subordinate.

Second, the plot line about the Russian visitors breezily glosses over what are some difficult questions about civilizational difference as it plays out in the space of Lebanese culture. There is both a good deal of self-Orientalizing and cultural mimicry at work here. The notion is that Western women’s sexuality is “modern” and liberated; “traditional” women are circumscribed by unbreakable bonds of family, region, and religious community. We also get the impression that linguistic and cultural barriers are indicative of essential differences between the backwards Lebanese (Arab?) personality, with its seductive sensuousness but uncontrollable sectarian urges, and the disenchanted Russian women. If the village is a laboratory for a particular kind of cinematic fantasy, I would caution that this naturalized version of sectarian and gender difference may feed right into conceptions among Western audiences of a rigid East-West binary, one that is effectively re-inscribed by the presence and transgressive action of the Russian floozies. Their arrival, simply put, disrupts local “tradition” and introduces sex, drugs and rock and roll.

But despite the film’s obvious intentions, its treatment of sectarianism is ultimately naïve and reified. Its playful jabs against religious intolerance, and apparent commitment to ideals of tolerance and co-existence notwithstanding, the major problem with the movie is the way in which it re-inscribes sectarian difference as inherently natural or primordial. Try as they may, the women seem unable to cool the boiling blood in their husband’s veins, that preternatural urge to satisfy their lust for vengeance with further violence against the “other” sect, unless that energy can be dissipated through sexual sublimation. There is a sincere attempt to reflect on the fact that when it comes to acts of communal violence, it is men, rather than women, who are most often the agents of barbarism—but one need not be a feminist to make this observation. Perhaps even more problematic, because the film asks us to inhabit a world of allegory rather than history, there is no indication that the functioning of sectarianism is tied to any broader processes of education, socialization, or politics. The smallest hint we get of this is in the sense that the radio, the television and the newspapers foist sectarian consciousness upon the people in the village, activating their latent sectarian sensibilities, and if the women can successfully drown out all that media noise, they can keep sectarian conflict at bay.

But these are minor flaws Nadine Labaki has made a satisfying film, one that celebrates the music, the food, and the good humor of Lebanese culture in its best senses. The film is beautifully shot, oscillating between chiaroscuro night scenes and bright ochres and olives, as the gorgeous cast and the idyllic mountain village is bathed in Mediterranean light. Moreover, Where Do We Go Now? is a laugh-out-loud film about sectarian violence—and that in itself might be the chief indicator of its seriousness and craft. Nadine Labaki deserves high praise for continuing to help put Lebanon on the map of international cinema—and in the career that lies before her, she will have plenty of time to tackle all of these issues with more nuance.

The film ends where it began, in the village cemetery. The entire village sets off to bury Nassim, with all the women still dressed in their “sectarian drag.” When they arrive at the cemetery, however, the pallbearers are confused, asking, “Where do we go now?” No one knows where the body should be buried. This is how the movie ends, leaving the title question hanging in the air. At one level, the question seems to be somehow mal posée, as one can never be fully neutral or stopped amidst the inexorable flow of time. On the other hand, however, this attempt to turn the space of cinema into a broader dialogue session, along the lines of the one that was held within the film itself, is most welcome, and one hopes that through screenings in Lebanon and beyond that such level-headed discussions will indeed take place, with or without hash-laced baked goods.