“Let there be no doubt,” President Obama declared in his 2012 State of the Union address. “America is determined to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon, and I will take no options off the table to achieve that goal.” The comment drew a rousing and sustained standing ovation from the US Congress. “But a peaceful resolution of this issue is still possible,” the President continued to a smattering of applause that tumbled awkwardly across the silent chamber. The spectacle would suggest war on Iran seems not just a viable but perhaps even a highly popular prospect on Capital Hill.

War talk holds a certain appeal. For an American president facing a difficult re-election campaign, war talk is shorthand for personal resolve and strength. It signals support for the military at a time when cuts to defense are essential. It crosses deep partisan divides in Washington, however momentarily. War talk helps push China and Russia to support crippling sanctions they have long resisted; rather than punishing Iran, the sanctions can now be posited as an attempt to stave off impending war on Iran which they oppose. And war talk reassures Israel’s Likud leadership that they wield enormous influence over American policy-making.

The Military Option

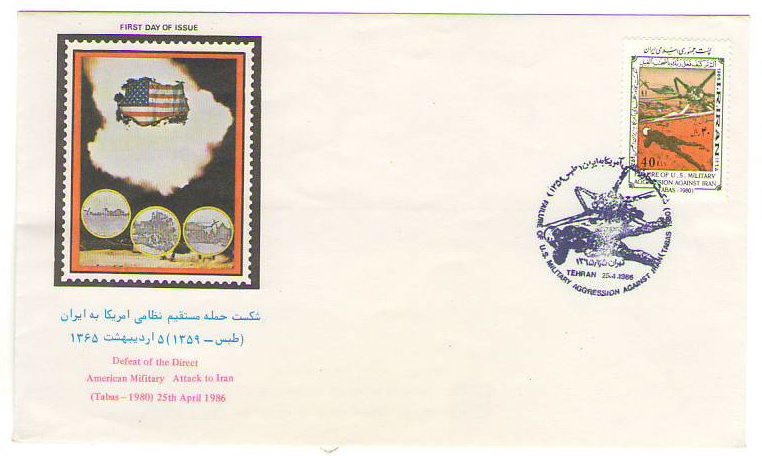

Every US president since Jimmy Carter has kept the military option on Iran on the table. Indeed, some US presidents have used the American military as a direct tool in dealing with the Islamic Republic of Iran. In 1980, President Carter famously carried out a failed rescue mission of America’s hostages. “The mission was a complete disaster,” concludes Charles Tustin Kamps, a professor of war games at Air Command and State College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama. The image of American military helicopters crashed in the Iranian desert appears on a postage stamp of the Islamic Republic, which recalls it as the “defeat of the direct American military attack to Iran.”

[Iranian stamp commemorating failed US rescue mission. Image from unknown archive.]

In 1994, President Clinton dubbed Iran “a rogue state.” The following year, he declared “a national emergency,” imposing comprehensive trade and financial sanctions on Iran with Executive Order 12957 which began:

"I, William J. Clinton, President of the United States of America, find that the actions and policies of the Government of Iran constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States, and hereby declare a national emergency to deal with that threat."

In 2008, Seymour Hersh, a preeminent investigative journalist, warned of a secret war on Iran, arguing, “President Bush’s ultimate goal in the nuclear confrontation with Iran is regime change.” The latest calls for war on Iran grew louder when a mid-level Iranian official recently renewed a perennial Iranian threat to close off the Straits of Hormuz. A highly knowledgeable analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Anthony Cordesman, concluded that, at best, Iran could close the Straits for “a few days to two weeks.” Iran would do so, Cordesman argued, knowing it would sacrifice all of its military assets in the Gulf, “suffer massive retaliation, and potentially lose many of its own oil facilities and export revenues.” After all, the closure of the Straits would devastate Iran’s already ailing economy. But war talk diffuses the impact of such logical, knowledgeable assessments.

Last week, the US aircraft carrier named the Abraham Lincoln returned to the Fifth Fleet in Persian Gulf. Its presence ensures that the Straits of Hormuz remain open, and it reminds the Iranian regime that a devastating attack with Tomahawk missiles is feasible. During Operation Iraqi Freedom, the Abraham Lincoln launched 16,500 sorties over Iraq and Afghanistan. The maneuver strengthens the hand of hawks who argue for a strong US military presence in the Gulf even after the United States has withdrawn from Iraq. War talk serves as a powerful counterpoint to those, like Toby Craig Jones, who persuasively argue the presence of the Fifth Fleet confounds US diplomatic options in Bahrain and beyond.

And like the Reagan era, President Obama’s war talk is carefully calibrated to be multi-lateral. It embraces not just traditional US allies in the Middle East, but also those in Europe. This week, European Union ministers in Brussels agreed on an oil embargo of the Islamic Republic. Heading into his 2012 re-election campaign, President Obama hopes to count a strong response to Iran among his diplomatic successes. During his State of the Union address, with Secretary of State Clinton nodding her approval from the audience, President Obama told the US Congress:

“Through the power of our diplomacy, a world that was once divided about how to deal with Iran’s nuclear program now stands as one. The regime is more isolated than ever before; its leaders are faced with crippling sanctions, and as long as they shirk their responsibilities, this pressure will not relent.”

It would seem that Obama’s war talk is designed to isolate Iran diplomatically, damage its economy, and threaten to destabilize the regime. A chastised Islamic Republic, it is assumed, will likely bend to American pressures to stop its nuclear program. The good diplomacy of which President Obama is rightly proud could be put to good use by calling on all parties, including saber rattling allies, to back down from rhetoric hostilities and covert operations that are escalating the threat of war with Iran.

Moving Beyond War talk

One of the dangers of war talk is that it creates a highly volatile atmosphere in which logic and history are pushed aside. As we have seen, the threat of war with Iran has been a cyclical feature of the American political landscape. Since 1979, various triggers have renewed war talk, setting into place reactions against it. Op-eds calling for cool heads to prevail are written. Roundtables of Iran experts are convened at universities. Petitions are circulated, protests are staged. It would be good for Obama’s advisors to recall the limits of war talk which, in the past, has not succeeded in bowing the Islamic Republic or in producing regime change.

The underlying premise of much of the latest wave of war talk is that the Obama administration has two bad choices to make: go to war with Iran or let the Islamic Republic of Iran develop nuclear weapons. This false binary is based on the false premise that we have irrefutable, actionable evidence that Iran is indeed developing nuclear weapons—and that it is close to achieving such a goal. The latest International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Report is hardly definitive. This assumption also overlooks the critical importance of nuanced diplomacy based on historical, political, and cultural knowledge of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton would do well to remember that the Iranian regime has a proven record of withstanding protracted war. Indeed many of its coercive and propagandistic instruments of power were created during the eight years of war with Iraq in the 1980s. Those networks of power remain at the regime’s disposal today. It is highly doubtful that the military option will bring about regime change. Those who look to the examples of the fall of Muammar Qaddafi and Saddam Hussein to the ravages of war should also bear in mind that their regimes were not replaced by governments that ensure regional security or domestic freedoms.

In determining the best available foreign policy options, the Obama administration should be cautious of those who align US policy with that of its allies. Saudi Arabia and Israel each have long, complicated histories with Iran. Seeing a war on Iran through these lenses might leave the United States with only bad options. President Obama can show genuine leadership by decoupling American policy on Iran from its relationship with Israel.

And although Iran is diplomatically isolated, a military strike against Iran by the United States and/or its allies will likely unite world opinion behind Iran regardless of how unpopular its regime may seem. Iranian history shows time and again that in the face of foreign aggression, Iranians rally behind their flag, regardless of how unpopular or repressive the government may be.

Even Iranian-Americans, whose political views on Iran diverge significantly, stand united against a war, especially after having witnessed the disastrous impact of the war on Iraq.

What Is To Be Done?

President Obama should call on knowledgeable partners to help create a path through the fog of war talk towards a peaceful resolution of the current impasse. The Turkish government could help create pipelines of quiet, private discussions. Certainly, the current US Ambassador in Turkey knows Iran better than most in the State Department. Mohammed El-Baradei, who won a Nobel Prize for his work as the IAEA Director, could be another knowledgeable resource in these negotiations.

After a decade of war in Afghanistan, it appears that the only sound exit strategy for the US involves negotiations with the Taliban. A war with Iran would likely result in similar scenarios. And a basic rule of diplomacy is that negotiations are most successful when all sides make sacrifices but appear to their constituents to be winners. All countries negotiate better from a place of strength. Bullying the Islamic Republic before sitting down to serious talks actually jeopardizes the success of diplomacy.

When regime change stops being a covert or open aim of the American government, the Islamic Republic will be forced to face its own citizens. No longer will it be able to blame the US for its economic woes, or to crack down on domestic opponents as agents of the US or the UK. The Islamic Republic’s main aim always has been to stay in power. It always has reserved its harshest treatment for the domestic arena. This seems a difficult lesson for American leaders to understand. Let the weapons inspectors do their work, let Iran’s internal opposition run its course. This is our best hope for a lasting resolution to “the Iran problem.”

The military option has been on the table ever since the hostage crisis began in November 1979. Since then, American aircraft carriers either have been in the region or on the ready to head there. Since then, American war games have focused mainly on Iran. A revolving door of DC think tankers—with a range of expertise that excludes Iranian history and politics or Farsi fluency—have alerted us that war on Iran is imminent, essential, feasible, even desirable.

Wars are not effective policy tools. They are not cheap or easy. Wars do not bring about regime change; they can lead to the death of leaders but not to substantive changes in governance and society. Wars do not bring about democracy; more often than not they lead to greater unrest and violence that triggers the exodus of the very segments of society most essential to building democracy. Wars do not make the United States more secure; if so, after a decade of “war on terror,” hundreds of thousands dead, and billions of dollars spent, the security alert should be at green (low risk of terrorism). Now is the time for President Obama to show resolve and strength by silencing war talk and steering his administration’s Iran policy to more fruitful grounds.

![[President Obama delivers 2012 State of the Union address. Image from unknown archive.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Obama2012StateoftheUnion.JPG)

.png)