With the passing of Pope Shenouda III, the journalistic shorthand that has emerged in discussing the current situation of Egypt’s Coptic Christians is that the loss has come at a difficult, precarious time for the community. In the midst of the uncertainty looming over the country as a whole, with the military still ruling Egypt and presidential elections in the offing, the Copts are said to bear a double burden – both that borne by all Egyptians as a consequence of last year’s uprising, and one particular to Christians, namely, the apparent revival of sectarian tensions dating to last year’s bombing of an Alexandria church. In the wake of the notorious New Year’s bombing in Alexandria, Copts came together, in defiance of the Church hierarchy, to mount a series of unprecedented protests, particularly at the Radio and Television Building in downtown Cairo, commonly known as “Maspero.” As one such protest unfolded last October, Maspero became the site of one of the worst massacres of Copts in modern Egyptian history – and the root of the sense of fear and dread that is said to hang over the community.

But this resume of the past year’s events will not suffice in accounting for the Coptic community’s current situation. The passing of the Pope affords an opportunity to undertake a broader analysis of Coptic communal dynamics and their impact on relations both with the state and with Muslims. What this broader analysis will reveal is that Egyptian politics and Coptic communal dynamics are deeply intertwined, to a degree often disregarded both by Copts and by Egypt analysts. This analysis requires a step back to the 1950s, and the rise of Pope Shenouda’s predecessor, Pope Kirollos VI.

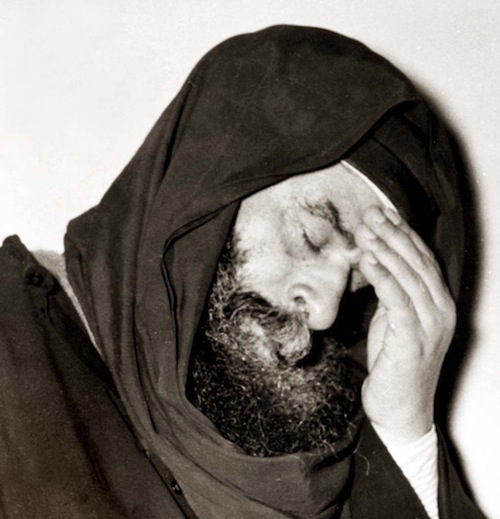

In 1927, Kirollos, who was then 25 years of age and known by his birth name Azer Yusuf Atta, left a job at the Thomas Cook and Sons agency in Alexandria and entered a monastery, Dayr al-Baramus. Upon his arrival at al-Baramus, the young man adopted the name Mina al-Baramusi. Always in search of seclusion, Mina moved from cave to cave at the monastery, and was labeled “the loner.” Renowned for his spirituality, Mina is said to have performed miracles, which are exhaustively documented in hundreds, perhaps thousands, of texts. And with his rise as Patriarch, Mina, who would take on the name Kirollos, retained this reputation. Arguably, this is how he is most often remembered today – as a profoundly pious and devout man who straddled the worlds of the mundane and the divine. Copts from throughout the country flocked to the Patriarchate in search of his blessing and guidance, and Kirollos received visitors well into the night. Whereas his predecessors had often neglected Cathedral services, he insisted on leading the services himself, and devoted himself to constant prayer.

[Pope Kirollos VI, Image Source: Memory of Modern Egypt archive of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina.]

However, in dwelling upon the miracles of Kirollos and his extraordinary spirituality, both Copts and Egypt analysts have neglected the remarkable effort the Patriarch expended in building up the Church as an institution. The Patriarch expanded the postgraduate Institute of Coptic Studies, which the Church had created in 1954. Researchers at the Institute studied Coptic language, history, art, archaeology, theology, and canon law. They sought to microfilm all the antiquities of Egypt’s churches and monasteries. Kirollos expanded the Coptic Seminary and, in 1960, made graduation from the Seminary a requirement for all priesthood candidates. In 1962, Kirollos began to appoint bishops without territorial dioceses – a step without precedent – and established portfolios for Public, Ecumenical, and Social Services, and for Education. Further, the Patriarch expanded the Sunday School Movement: in 1963, the Church claimed that the Movement reached one million students between the ages of five and sixteen through 4,000 branches and 5,000 teachers.

Through the Sunday School Movement, which dated back to the interwar period, Coptic youth had become increasingly aware of their Church’s origins and their community’s heritage. This knowledge led them to conceive of their identity in a new light, and young, educated Copts, often professionals, were inspired to enter monasteries and the Patriarchal College. Among them was Nazir Gayyad — a student of history who had both served as a military officer and contemplated a career in journalism prior to his graduation from the College in 1949. Nazir was acutely aware of a lack of leadership in Coptic communal affairs, and spoke of a need to rally the community around the Church. With his appointment as Bishop of Education in 1962, Nazir — known thenceforth as Shenouda — was afforded the opportunity to mobilize the community at large behind his vision. Each Friday, he delivered a lesson in the Cathedral on such matters as dating, studying, family planning, and class relations – issues central to the daily lives of Copts. Coptic youths were particularly drawn to the lessons, and Shenouda could attract 10,000 of them each Friday.

These efforts to build up the Church proceeded in tandem with efforts undertaken by Kirollos to cement a partnership – what I have termed, in my past scholarship, a ‘millet partnership’ – with President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Under the terms of this partnership, Kirollos as Patriarch presented the concerns of the community directly to the President, and promoted loyalty to the regime among Copts. In exchange, Nasser guaranteed the security of the community and the status of the Patriarch as the Copts’ sole legitimate representative. On this score, the most important step Nasser took was to dissolve the Lay Council or majlis al-milli, through which elite Copts had repeatedly sought to limit the control of the clergy over Church finances. For his part, the Patriarch moved in lockstep with the foreign policy of the regime, attacking the remaining vestiges of colonialism in Africa and condemning American involvement in Vietnam. Indeed, in the wake of the 1967 War, Kirollos would send Church representatives to Washington, London, Paris, the Vatican, and the headquarters of the World Council of Churches in Geneva, to spread Nasser’s perspective of the conflict. The quintessential image of the Nasser-Kirollos partnership is that of the President laying the cornerstone of the Cathedral of Saint Mark in Abbasiyya on July 24, 1965.

[President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Pope Kirollos VI. Image Source: Postcard collection compiled by author]

After President Nasser’s death, Anwar Al-Sadat revived Islam as political idiom in Egypt, in an effort to destroy the roots of Nasserism in government and among Egyptians. These were the circumstances under which Bishop Shenouda was elected the 117th Patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church in October 1971. Due to the ‘Islamization’ program embraced by Sadat, the partnership between Patriarch and President cultivated by Kirollos was in tatters. By November 1972, in an atmosphere charged with sectarianism, an unauthorized church in the Delta village of Khanka was set ablaze, and Shenouda sent a hundred priests and four hundred laymen to pray at the site of the arson. The incident displayed the resolve of the Patriarch and infuriated Sadat. Through a series of conferences, Shenouda publicly opposed the efforts of the regime to foreground Islam in the public sphere. The conferences demanded government protection of Christians and their property, freedom of belief and worship, an end to the seizure of Church property by the Ministry of Religious Endowments, the abandonment of efforts to apply Islamic law to non-Muslims, as well as greater Coptic representation in labor unions, professional associations, local and regional councils, and parliament. Ultimately, Shenouda found himself swept up in the purge of purported regime opponents that shortly preceded Sadat’s assassination, and he was placed under house arrest at the Monastery of Saint Bishoy.

.jpg)

[Pope Shenouda III. From Wikimedia commons]

Vital to Shenouda’s success in his defiance of the state during the 1970s was his mobilization of the Coptic community — specifically, the Coptic middle class. The Lay Council, dissolved under Nasser, was reinstated in 1973, and the membership was drawn heavily from the middle class. By 1974, the Bishopric of Public, Ecumenical, and Social Services had created a network of Community Development Centers throughout the country. The Centers organized Christian education and reading programs, and provided women with work to augment their families’ incomes. In 1976, the Bishopric had created two centers to provide high school dropouts with vocational training — in carpentry, plumbing, auto and television repair — and a family planning program. By 1978, a series of language centers had begun to train disadvantaged Copts in English. This network of social services developed under Shenouda enabled middle-class Copts to survive in the midst of a rapid contraction of economic opportunity. The policy of economic liberalization, or infitah, heralded by Sadat in 1974 as vital to Egypt’s future, had failed to attract foreign capital to the degree the President had expected; and only a select class of Egyptians benefited from the capital that entered the country, with contractors and land speculators foremost among them. Factory workers, peasants, and members of the civil service fared terribly under infitah, not least given the inflation that the policy spawned.

While under house arrest, Shenouda reconsidered his approach to leadership of the community. Specifically, he looked back to the partnership his predecessor, Kirollos, had developed with Nasser, and used that partnership as a model for his relationship with Egypt’s new leader — Sadat’s Vice-President, Hosni Mubarak. As part of this strategy, he would cooperate with the regime, embrace the rhetoric of national unity, negotiate with the government behind the scenes, avoid public confrontations, and consolidate his power within the Church. Under the partnership, Mubarak furnished the Patriarch with resources — permits for church construction, for instance — which Shenouda would then distribute among dioceses.

Importantly, this partnership denied Coptic laymen a role in both communal and national affairs – despite the fact that the Patriarch had rallied the Coptic middle class behind him during the 1970s, and had relied upon middle-class support in his confrontation with Sadat. Indeed, the dilemma Shenouda faced after his return from house arrest was that of controlling the middle-class activists he had once spurred to action. Through his partnership with Mubarak, Shenouda sought to consolidate not merely his position as head of the Church, but his position as head of the community as well. His voice was cast by Church and state as the only legitimate public voice of the Coptic community. Ultimately, the Patriarch’s grip over Church affairs prevented the Coptic middle class — the Copts whom Shenouda had galvanized in his Friday lessons and propelled into Church participation — from reforming the religious organizations at the center of their lives, in accordance with their shifting needs. More broadly, the result of the partnership between Patriarch and President is that there exists no secular leadership of the Coptic community untainted by complicity with the government — no independent voice willing and able to voice Copts’ grievances.

[Clashes between protesters and security forces in Maspero on 9 October 2011. Image from Demotix.]

And this leads us back to the beginning, for this is, to a large extent, what the protests at Maspero were about. The Coptic protests at Maspero need to be understood not simply as a response to those who burn churches, or to government officials who approach violence against Copts in a cavalier manner. The protesters were sending a message not only to the Egyptian state and to Muslims, but to their Church leadership as well. To demonstrate in that way was an act of defiance against the Church, and specifically, against the Church hierarchy’s partnership with an authoritarian state.

Copts, particularly those whose sympathies rest firmly with the revolution, find themselves in a precarious position. They find themselves confronted with the charge of sectarianism when they speak, as Copts, in the public sphere. But they find themselves at odds, further, with a Church hierarchy that has long sought to appropriate their voice – a Church hierarchy that was partners with the old regime, and that, for the moment at least, seems impervious to the revolutionary forces sweeping across Egypt.