On the evening of 29 March, a line in my twitter feed read, “You don’t want to mess with Iran’s lady ninjas.” Cara Park’s snarky comment had been retweeted by someone I follow in Cairo. I clicked her link to find she’s a deputy managing editor of Foreign Policy, blogging on the suspensions of Reuters’ accreditation in Iran over their reporting on women training in ninjutsu:

In case it wasn’t obvious, you don’t want to offend a highly-trained cadre of Iranian ninjas. Anger these black-belted beauties and they’ll … take their legitimate complaint to the appropriate authorities who will suspend your press credentials. Hiiiii-yah!

It may be time for Foreign Policy to have an editorial meeting about its ab/use of humor.i Ironically, Parks herself warns of “glibly labeling a group in a way that plays into stereotypes about violence is no laughing matter.” But then, can’t help but end with another chuckle. Posting a picture of one of the Iranian ninjutsu practitioners Parks says, “Don’t believe us? Why don’t you tell her that.” Academics are often rightly accused of being too insular. The same could be said of some journalists, especially those who work for social media sites. One wonders if there isn’t too much pressure to get more “likes,” retweets, mentions, and followers. Brevity and witticism have become valued tools of the trade. Behind Parks` superficial and sarcastic blog is a complex and troubling picture.

Journalists and Iran’s “Ninjas”

The story began on 2 February, when Press TV uploaded a report on women practicing ninjutsu in Iran. Part of Iran’s state-controlled media, Press TV regularly presents feature stories meant to show life in Iran through the lens of the Islamic Republic. Here was a story of a modest dojo in Karaj, a town on the outskirts of Iran’s capital, where a handful of women were shown demonstrating rather impressive martial arts skills. Sensei Akbar Faraji tells us ninjutsu was introduced to Iran in 1989 and now has some 24,000 members of an official club. “Being a ninja,” Faraji said,” is about patience, tolerance, fortitude.” Fatemeh Moamer, a ninjutsu instructor explained, “The most important lesson of ninjutsu is respect and humility. They learn self-respect.” The Press TV report used slow motion and music for dramatic effect. To be fair, ninjutsu is incredibly dramatic. But that’s the point of a lot of martial arts, according to practitioner and scholar Deborah Kelns-Bigman who has forwarded a theory of martial arts as performance art.ii

My husband, who has been practicing karate and kung fu for the past fourteen years, tells me that in some martial arts looking fierce is an important part of overcoming your opponent. The images of Iranian women looking fierce as they practiced martial arts went viral. Reuters soon did their own story on the same dojo, but their headline read, “Thousands of Female Ninjas train as Iran’s Assassins.” Several other media outlets picked up the Reuters report. “Iran trains female ninjas as potential assassins,” announced The Telegraph on 18 February. Below this headline, we see a brief video of women demonstrating their ninjutsu skills. The only commentary is a quote from Sensei Faraji: "What is important to me as an Iranian and as a coach is that I have to do this job. We must have strong women, able women. And for the defense of our country, we will do anything.

In the accompanying article, we read:

Scores of black-clad female ‘ninja’ fighters … are being trained as lethal warriors at a school in Tehran…. One of the fighters who has been training for over thirteen years said, “Our aim is for Iranian women to be strengthened and if a problem arises, we will definitely declare our readiness to defend our Islamic homeland.”

The rest of The Telegraph article is about suspicions that Iran is “planning to make nuclear weapons” and “pursuing weapons of mass destruction.”

Rupert Murdoch’s iPad publication, The Daily, ran the video under the headline, “Iranian Ninjas,” noting “the nation’s women have embraced the ancient Japanese warrior training.”

… A female Iranian assassin who disappeared from Bangkok in the wake of the failed anti-Israeli bomb plot is reportedly back in Tehran today. The new wrinkle comes as blame is cast upon Iran for a recent spate of botched terror attacks — and as Iran brags about its battalion of female “ninjas” who they say are trained to kill…the continuing revelations about a rash of assassination attempts against Israeli diplomats are shedding light on a global shadow war fit for a Hollywood thriller.

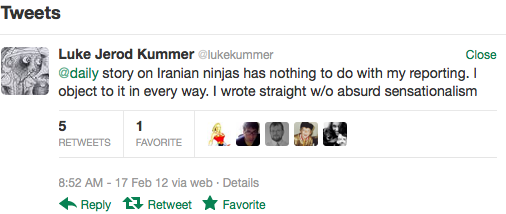

Fiction melded with facts, and the martial artists in Karaj were presented as trained assassins working for the Iranian government. Shortly after the article appeared on The Daily, its apparent author, Luke Jerod Kummer sent out a twitter disavowing the report.

According to Jim Romenesko who blogs on the media, Kummer had “tweeted his objection to the handling of his reporting a half-hour after resigning from The Daily.” Kummer then received a letter from Murdoch’s company, noting his tweet and threatening to sue him on the basis of a Non-Disclosure/Non-Compete Agreement. Kummer hasn’t tweeted since.

“The episode,” wrote Eric Wemple of The Washington Post, “helps answer a perpetual question about Murdoch properties: How far will they stretch to sexify their journalism.” Indeed, how much innuendo, exaggeration, or outright lying are we to tolerate from the press?

And this is the root of the objections of the Iranian women martial artists. Press TV’s reporters returned to the dojo, filing an update on March 28. One athlete complained that being dubbed assassins harms their chances to compete internationally: “We want the whole world to know that Reuters has lied about us.” The athletes claim that the Reuters journalist asked them what they would do if their country was attacked and then reported their responses out of context.

Martial Arts and Feminist Rage

On February 19, The Guardian produced a slideshow of the Retuers photographs with a caption, “Iran’s female ninjas: fighting for sexual equality.” In the accompanying article, Lucy Managan quipped:

For those times when Betty Friedan just isn’t enough…ninjutsu is here to help. …It turns out that when you’re denied basic human rights, restricted in your ability to dress how you want and mix with the people you choose, and when your legal testimony is officially recognized as being worth exactly half that of a man’s, you develop—if these images are anything to go by—a lot of rage.

Unfortunately, Managan herself took a decidedly non-feminist stance in her reporting by completely ignoring the women athletes’ own comments. And it may be news to Managan, but feminism is hardly the exclusive purview of middle class white women like Friedan. Iranian women searching for feminist inspiration are more likely to read Simin Daneshvar’s novels, recite Forugh Farrokhzad’s poetry, watch Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s films, or contemplate Shirin Neshat’s art.iii This is a common double-bind of Iranian women. Even as they are denied important rights in Iran, too often they become reduced to voiceless, mindless symbols with no agency of their own by Western writers, journalists, and academics.

Almost all the reporting on the dojo in Karaj paid little heed to the practice of martial arts. While ninjutsu, like many other forms of martial arts, is rooted in a warrior tradition, its contemporary practice is an athletic not militaristic enterprise. As one scholar explained, “There are no ninja today, only practitioners of some of the techniques and students of the tradition. Achievement of some rank within a school teaching ninjutsu cannot make one a ninja, any more than learning techniques with the sword can qualify one as a samurai.”iv

No doubt, the practice of martial arts in general is gendered. The growing popularity of martial arts by women in the U.S. has ties to the feminist self-defense movement. A martial arts workshop organized by the Nutcracker’s Suite Karate and Self-Dense School in Northampton, Massachusetts in 1977 featured political workshops that sought to connect the physical training to an “understanding of violence against women, the roots and magnitude of acts of harassment, child molestation, wife abuse, rape, and murder…”v Indeed, Iranian women’s participation in martial arts is part of a larger global trend. Women benefit from the physicality of martial arts, but also from the enhancement of a mind-body connection. But it’s a truism that much of the reporting on Iran happens in isolation—underscoring a sense that Iranians are essentially different from and separated out of broader social and political phenomena.

There is, of course, a particular history of Iranian’s participation in martial arts that the coverage by and large ignored. “Iran’s revolutionary ax,” reported UPI on July 3, 1979, “which has already banned liquor, drugs, and mixed swimming, fell Tuesday on Bruce Lee and kung fu films.” Though Bruce Lee’s film, “The Fist of Fury,” was still showing in a Tehran cinema, “the fate of more than a dozen karate and kung fu schools in the capital was not known.”vi As it turns out, the Islamic Republic’s prohibition on many popular forms of entertainment—viewing the latest Hollywood blockbusters at the local theater, gambling at casinos, drinking at bars, dancing at nightclubs—led to the rise of other forms of public sociability that abided by strict moral codes established by the state. More and more Iranians participate in sports and attend sporting events as a regular pastime. And since the revolution, martial arts have become widely practiced in Iran. There are competitions at the collegial, regional, and national levels supported by various official leagues and a national martial arts federation.

Sports have become a site of contested power in the Islamic Republic.vii On the one hand, they provide a venue for public sociability; in turn, the government imposes restrictions on sports in order to extend its control over public space and citizens’ bodies. When the government put in place systematic gender segregation, Iranian women were prohibited from participating in international sporting events, barred from attending soccer matches in stadiums, and forced to ski on separate slopes and swim on separate beaches. Overtime, as women have struggled for more rights and Iranians have demanded more social freedoms, the gender boundaries of sports have shifted. And the impulse to control Iranians’ bodies rubs against the government’s desire to win prestigious awards in international arenas, like the World Cup and the Olympics.

Within this complex web of power and control, Iranian women athletes have gravitated towards sports that can be reasonably practiced in the mandated “modest” Islamic attire and whose international governing bodies have flexible dress codes. Gradually, Iranian women began to participate in international competitions in shooting, shotput, skiing, and martial arts. In 1996, Lida Fariman joined the Iranian national team at the Atlanta Olympics as a shooter. In the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, Iran had three women athletes in rowing, archery, and taekwondo. In 2010, alpine skier Marjan Kalhour became the first Iranian woman to participate in the winter Olympics.

In 2007, the Iranian Olympic Committee had issued new guidelines for “proper behavior” of male and female athletes participating in international sporting competitions to counter their “subjugation to western customs and practices.” Women athletes cannot train or travel with male coaches; male referees should not touch Iranian women athletes, even to raise their hand in victory.

Meanwhile, tailors got busy, experimenting with materials like Velcro and lycra to create new forms of hijab that would allow Iranian women to participate in soccer tournaments. Soccer—or football as it is commonly called outside the U.S.—is the most popular and prestigious sport of all in Iran. A women’s league was a great step forward for Iranian women athletes. But in June 2011, as the national team prepared for a qualifying match for the 2012 London Olympics, FIFA decreed their head covering was in violation of the official dress code. They were disqualified and were forced to forfeit their match to Jordan.

The larger struggle over gender politics in Iran is refracted through sports. In the 1990s, Faezeh Hashemi, a former MP and the daughter of the former Iranian President, “championed the right of women to have access to sports facilities and competition as the head of the Islamic Women’s Sports Federation. In that role, she increased access for women to swimming pools and tennis courts and golf driving ranges.”viii But Iran’s women athletes remain caught in a web of government control within Iran while their modest Islamic attire makes them subject to prohibition by international sporting bodies.

And now some careless or unethical journalists made the women athletes in the Karaj dojo the butt of jokes or props in their jingoistic drum beating for war on Iran. More power to them for speaking out for themselves. Unfortunately, the whole sordid affair provided the Islamic Republic a handy excuse to withdraw Reuters’ credentials, making it even harder for us to get accurate reporting from Iran at a critical time. Above all else, the story of Iranian women martial artists turns out to be a cautionary tale.

_______

1. They also have an “Iran meter” that they use for many of their stories on Iran. Shaped like a mushroom cloud with a missile as a marker, it apparently rates the possibility of war with measures like “Nukes of Hazard” and “Bombs Away.”

2. Deborah Klens-Bigman, “Toward a Theory of Martial Arts as Performance Art,” in Combat, Ritual and Performance: Anthropology of the Martial Arts, ed. David E. Jones (Wesport, Praeger, 2002), 1-10. I thank Michael Kennedy for sharing his vast knowledge of martial arts as well as helpful books on the subject from his personal library.

3. I highly recommend Maya Mikdashi’s excellent article, “How Not to Study Gender in the Middle East,” to Ms. Managan.

4. G. Camron Hurst III, “Ninjutsu,” in Martial Arts of the World, vol. 1, ed. Thomas A. Green (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio, 2001), 361.

6. Sajid Rizvi, “Iran’s Revolutionaries Ax Kung Fu Films,” Sarasota Herald Tribune, 3 July 1979, 9B. For more on the kinds of films that were banned, see Hamid Naficy, “Islamizing Film Culture in Iran: A Post-Khatami Update,” in The New Iranian Cinema, ed. Richard Tapper (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 26-65.

7. I highly recommend Wilson Chako Jacob’s excellent book, Working Out Egypt: Effendi Masculinity and Subject Formation in Colonial Modernity, 1870-1940 http://www.dukeupress.edu/Catalog/ViewProduct.php?productid=16572.

8. Isobel Coleman, “Faezeh Hashemi and Women’s Sports in Iran,” 20 January 2012, http://blogs.cfr.org/coleman/2012/01/20/faezeh-hashemi-and-womens-sports-in-iran/