Subversion. Featuring work by Akram Zaatari, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Khaled Hafez, Larissa Sansour, Marwa Arsanios, Sharif Waked, Sherif El-Azma, Tarzan and Arab, and Wafaa Bilal. Curated by Omar Kholeif. Cornerhouse, 70 Oxford Street, Manchester, UK. 14 April - 5 June 2012, preview/symposium 13 April 2012.

[Omar Kholeif is Curator of Subversion, a large-scale exhibition and public program, which runs until 5 June 2012 at Cornerhouse, Manchester, UK. More about Omar Kholeif here; follow him on Twitter here.]

Anthony Alessandrini (AA): What was the idea behind this show, and what made you decide to curate it?

Omar Kholeif (OK): The spark for Subversion clicked in my head in 2009. I had just come back from a frustrating summer in Egypt trying to find some material in a number of different deteriorating film archives, and when I returned to the UK everyone was buzzing about a show in London that had lots of so-called Middle Eastern (and Arab) artists in it. It was a show entitled Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East at the Saatchi Gallery in London. This triggered all sorts of emotions within me and many of the artists with whom I was working, both from within and from outside of the Arab world. At that point I felt, and I still feel much the same way now, that Western institutions were still talking about artists from particular parts of the world using the same rhetoric that originated from post-colonial writers in the 1990s. In a sense, we had never moved beyond outdated modes of identity politics. Instead, I wanted to talk about what it means to be an individual in a post-internet, post social media human condition.

[Akram Zaatari, How I Love You (2001). Film still, single-channel video. Courtesy of the artist.]

I started having a series of open conversations with Sarah Perks, who is Cornerhouse’s Programme and Engagement Director. After these initial discussions, I went back to the works and artists whom I found were urgently compelling—in particular, the films of Larissa Sansour and Sharif Waked. One of the themes that resonated most strongly, and which continued to re-surface through subsequent discussions, was this notion that artists from and of the Arab world felt that they had to perform to a sense of national or regional identity that politicians, the news media, and the art world and its cultural brokers had cast upon them. This sense of a performed identity runs throughout the exhibition, and is indeed what influenced the title of the show. The name Subversion indeed is intended to be ironic or playful—a critique of the fact that media only tends to think or dialogue in oppositional binary terms, especially when speaking of particular ethnic or geographical spheres.

With Subversion, in many respects, my goal is to utilize some of the same tropes or structures as essentialist media and exhibition making institutions (that is, focusing on a particular region in the world through subjective eyes), but instead of linking people or works of art together on the basis of geographical, ethnic, or political terms, I decided instead to connect works based on conceptual, theoretical, and aesthetic possibilities and questions.

[Larissa Sansour, clip from A Space Exodus (2009)]

AA: What particular themes, issues, ideas, and locations does it address? How is the title of the show meant to reflect back upon these themes and ideas?

OK: I like to think that an exhibition possesses a form of agency that is propelled by the work of the artists within it. As such, many of the curatorial projects that I work on are much more about the possibilities of offering up multiple readings and access points for audiences, as opposed to merely relaying a particular didactic theme. Having said that, the idea that links the artists within the show can be construed as a continual process of dissenting from the binary modalities of the mass media, and instead, fostering amorphous dualities for artists.

For example, in To Be Continued… (2009), Sharif Waked wryly pokes fun at the modality of the suicide bomber video by correlating this mode of address with the cyclical folklore of Scheherazade from One Thousand and One Nights. Marwa Arsanios, on the other hand, plays a different kind of role in her video, I’ve Heard Stories Part 1 (2008), which re-writes a secret history between men at Beirut’s infamous Carlton Hotel, told through a sketch-like animation utilizing the narrative language of a campy whodunit TV episode. This is complemented by two lyrical works produced early on in Akram Zaatari’s career (which are now rarely seen)—where the artist is found commenting on contemporary tensions between masculinity and longing.

[Akram Zaatari, Red Chewing Gum (2000). Film still, single-channel video. Courtesy of the artist.]

AA: How does this work connect to and/or depart from the previous work you have done as a curator?

OK: The gradual erosion of generic boundaries across disciplines, coupled with the cross-pollination of funding resources, now requires that contemporary curators possess a form of un-definable dynamism. This is even more essential when, like myself, one works at a cross-arts-form venue such as FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) or Cornerhouse (which are not merely art galleries, but also centers for knowledge exchange, cinemas, commissioning bodies, festival hubs, etcetera.) As such, all of my curating is uniquely defined on a project-by-project basis.

Still, I am inspired to show thoughtful and critical work whatever the context, but in the last five years, about half of my work has been dedicated quite specifically to forming opportunities for creative practitioners working in Arab countries. For example, I launched the only recurring Arab Film Festival in the UK in 2011 at the FACT center, as well as a number of touring film programs of Arab cinema, with the hope that it will pique new interest in popular forms of Arab culture (and not simply the elite cultural forms that actually possess much more concrete international distribution models).

My primary aim with these forums is to help develop a critical culture and a re-invigorated distribution mechanism for cultural outputs outside of the Arab region itself.

[Khaled Hafez, On Presidents and Superheroes (2009)]

This impetus is coupled with an overarching desire to help develop rigorous criticism in the Arab world, which is undeniably lacking at present. This has much to do with the rigid and hierarchic educational institutions in the region, but also the linguistic barrier. As such, both my curatorial and my teaching work aspire to develop a much more critical form of engagement. By having a broad stretch of so-called Arab culture exist freely alongside other works of international note, we will enhance a much more fluid approach to critical culture, and indeed, writing, evaluation, and theorization of the visual arts and culture in the Arab world. I am conscious that this is a complex and gradual process, but regardless, much of our current historiographic approach to Arab cultural criticism lacks the nuances that contemporary culture warrants.

AA: Who do you hope will come to see this show, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

OK: The majority of the audience for Subversion will be from the Greater Manchester area and the North West of England. Cornerhouse, as the city’s international arts and film center in many senses, has a public responsibility to engage the citizens of this community. My hope is that the show will reach as broad an audience as possible within the locality, both those who have an interest in the visual arts, and also those who don’t, but who may be drawn to the unique presentation of ideas within the exhibition. Manchester is one of the UK’s hubs for culture (along with Liverpool) outside of London, and boasts a diverse population. I would like for Subversion to resonate with the furthest reaches of these communities. Beyond that, I do very much hope that critics, writers, curators, and collectors who are involved with various forms of cross-cultural production will be taken by the show, whether they manage to make it in person, or whether they simply read about the exhibition’s resource materials online.

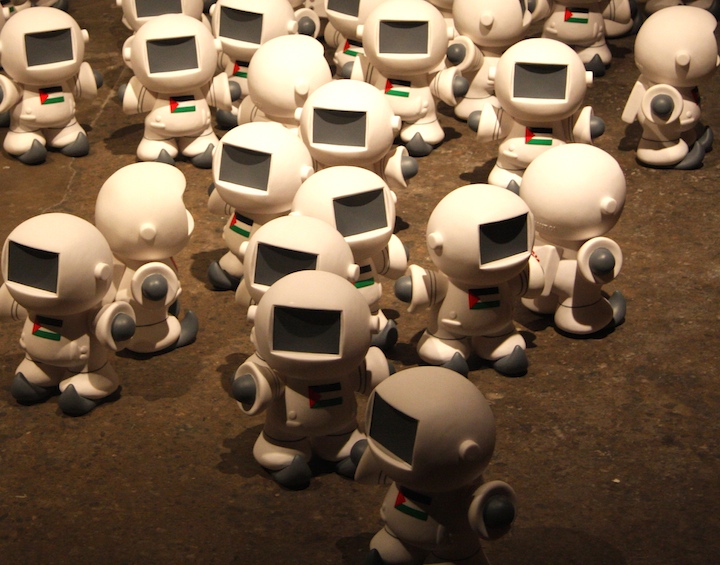

[Larissa Sansour, Palestinauts (2010). Hard vinyl sculptures, 30 x 25 x 20 cm. Courtesy of the artist.]

AA: How did you choose the particular artists and works featured in Subversion?

OK: The selection began with a series of conversations with writers, curators, and artists, many of whom are still involved in the project in some form or another now. This process was also further developed through two years of study, studio visits, reading, writing, and critical questioning of contemporary art and culture in an increasingly globalized and internet savvy context. Then l started to find thematic, aesthetic, and conceptual linkages and cross references that would add texture to the overall project.

In terms of the physical organization of the galleries, I conceived Subversion akin to a three-act play; each gallery presents a chapter in this imagined narrative trajectory. We start off in outer space, where we find Larissa Sansour re-invigorating Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, alongside an array of Palistinauts (2010) who can be found invading the gallery space. In our second chapter, audiences are suspended in disbelief as Sharif Waked plays with the modalities of the suicide bomber video, while Marwa Arsanios and Akram Zaatari simultaneously seek to re-author the hidden romantic and erotic history between men in the region. Our final chapter is turned into a playground for our audiences to engage, play, and tamper with. We begin with Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s Circle of Confusion (2001/2012), which invites viewers to un-pick a jigsaw puzzle constructed from an aerial view of their native Beirut. Elsewhere, Wafaa Bilal presents the UK premiere of Virtual Jihadi in a newly created installation consisting of a rickety internet café designed by production designer Kev Thornton. Finally, Tarzan and Arab’s Gazawood project is housed in a constructed retro cinema within the gallery, where audiences can sit back and witness the twins’ violent and poignant homage to the movies come alive.

[Tarzan & Arab, trailer for A Colourful Journey (2010).]

AA: How would you like to see this show intervene in or enter into conversations within the contemporary art scene?

OK: If the show would be so significant as to “intervene” or shift a narrow or essentialist discourse around contemporary art that exists outside of the North American/European axis, then that would be absolutely astonishing. However, I am not brazen enough to suggest that this would indeed be the result of such a venture. Rather, what I hope is that Subversion will offer alternative readings to what a “supposed” modernity in the “constructed” Arab world might be. To usher in a shared language or structure, whereby multiple, subjective, and conflicting dualities can exist within artworks—ones that are not reducible to an ethnicity, geography, or political rhetoric. I also hope that by doing this with a creative sense of humor, as I have attempted to with Subversion, that it will shift the subconscious visual associations of art in the region, which very often continues to fall into a niche defined by a presupposed cultural aesthetic.