4,275 security prisoners are Palestinians from the OPT… fourteen security prisoners are Jewish.

4,275 security prisoners are Palestinians from the OPT… fourteen security prisoners are Jewish.

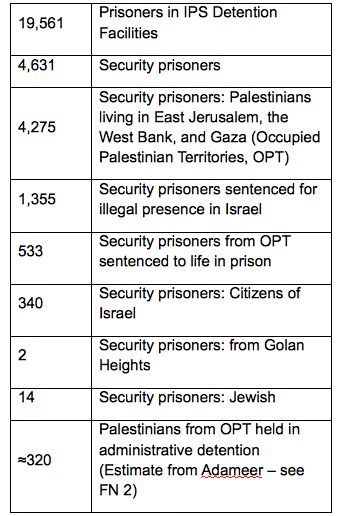

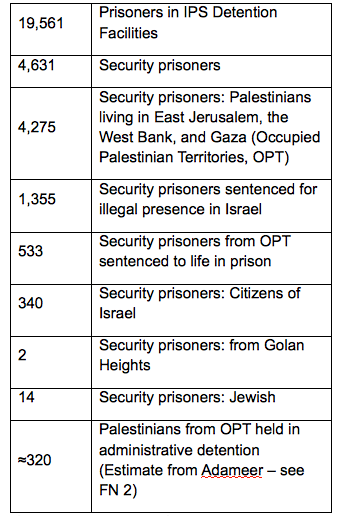

According to data that the Israeli Prison Service (IPS) provided to Adalah in a letter on 28 February 2012, there were 19,561 prisoners in detention facilities managed by the IPS, 4,631 of them were classified as "security prisoners." 4,275 of the security prisoners were Palestinians who are living in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza, 340 are Palestinians citizens of Israeli, two were from the Golan Heights, and fourteen were Jewish security prisoners. From the Palestinian prisoners classified as security prisoners who are from the West Bank and Gaza, 533 have life sentences. According to data and reports provided by human rights organizations, Israel holds about 320 Palestinians from the West Bank in administrative detention according to Adameer. In prisons under the responsibility of IPS, 1,355 Palestinian prisoners who were convicted for illegal presence in Israel are classified as security prisoners.

[Source: Israeli Prison Services, Updated February 2012]

Security prisoners are held under much harsher and more severe detention conditions than criminal prisoners, including prisoners detained for the same offenses who were classified as criminal prisoners by IPS.

The Supreme Court ruled that IPS is authorized to define security and criminal prisoners itself, and to take special measures regarding the security prisoners (see case: ICJ 221/80, Darwish vs. the IPS, PD 35 (1), 536 [1980]). Nonetheless, the court emphasized that the IPS should balance prisoners` rights with restrictions necessary to maintain security (see administrative appeal 7488/95, the State of Israel vs. Quntar, PD 50(4) 492, 500, 503 (1996).

Restrictions for security prisoners are not held on criminal prisoners. For example, family visits for security prisoners are restricted to first-degree relatives; security prisoners are prohibited from maintaining telephone contact with any person, including family; they are not allowed permitted leave from prison, even in special events such as death of a first degree family member. Furthermore, security prisoners` social needs are ignored. Security prisoners cannot have rehabilitation services or enjoy education opportunities that IPS provides to criminal prisoners. During visits from first-degree family members or the prisoner’s lawyer, transparent screens are separate the prisoner from his visitors. Security prisoners cannot get amnesty from the state`s president, and those sentenced for life have no opportunity to for reduction of punishment.

IPS tightened restrictions in 2011 on the thousands of security prisoners in its guard, purposefully worsening detention conditions. These restrictions include, for example, prohibiting on academic studies in the Open University, cancelling TV channels, and narrowing rules or prohibiting sending and receiving mail.

The Israeli government openly declared that it was taking measures to exacerbate security prisoners’ imprisonment conditions and deny their rights.

Tightening strictures on security prisoners was used as a form of collective punishment leading up to the release of the imprisoned Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit in June 2011. The Israeli government openly declared that it was taking measures to exacerbate security prisoners’ imprisonment conditions and deny their rights, beginning with cancelling security prisoners’ academic studies.

Some of these measures can be defined as cruel and inhuman treatment, contrary to international law. Amongst these measures are strip searching, use of violence as punishment, incommunicado detention, inadequate medical treatment for hunger strikers, prevention of medical care by independent doctors, and prevention of access to prisoners` lawyers.

In 2012, administrative detention without sentencing was widely applied. In response, administrative detainees declared a hunger strike—security prisoners joined them. Hunger strikers were punished through denial of their rights by, for example, depriving them of family visits.

In October 2011 approximately 1,000 Palestinian prisoners were released in return for Gilad Shalit in a deal between Israel and Hamas. However, the harsh conditions imposed on security prisoners were not lifted.

In fact, in March 2011, IPS imposed a new kind of collective punishment: seventy-six security prisoners, most of them are inhabitants of the Triangle and northern Israel, were suddenly moved from “Section 4” in Gilboa Prison, near Beit She`an and their family homes, to Nafha Prison, located in an isolated area in the southern Negev Desert. Their removal to the remote prison imposes additional difficulties to the prisoners and their families—especially for visitors who are elderly, ill, or children.

Section 4 of Nafha Prison: The cells are dirty, dark, and unventilated, with insects and cockroaches crawling from the mattresses.

In addition to the questionable reasons for the transfer itself and the problematic way it was undertaken, Section 4 of Nafha Prison, where the prisoners were sent, is in terrible physical condition that endangers the prisoners’ physical health. Prisoners reported to Adalah that ten prisoners are crowded into each small cell, with poor sanitation including no separation between toilets and showers. The cells are dirty, dark, and unventilated, with insects and cockroaches crawling from the mattresses. The prisoners also reported that the cells lack electric outlets, and blackouts take place regularly. Basic furniture such as closets, tables, and chairs are inadequate for the prisoners in each cell. In addition, the courtyard in Section 4 is not large enough to accommodate the prisoners during daily recess.

Adalah demanded that Section 4 be shut down promptly.

Adalah immediately wrote to the IPS Commissioner after learning of the prison transfer from Gilboa to Nafha demanding that Section 4 be shut down promptly. The two letters went unanswered. However, at the end of March 2012 Adalah was informed that prisoners held in Section 4 were moved to another section of Nafha Prison, but the new section had similar conditions. Additional prisoners from Ramon Prison were transferred into Section 4.

IPS’ overarching policy of harassment and strictures unrelated to security infringes on prisoners’ human dignity and constitutes cruel and inhuman punishment.

The transfer of seventy-six prisoners from Gilboa Prison to distant Nafha, their placement in wretched conditions in Section 4 and subsequent transfer to a similar section, and the transfer of an addition seventy prisoners from Ramon Prison to Section 4 appears to be a new form of collective punishment. However, collective punishment is characteristic of IPS’ policy towards security prisoners, who endure harsh imprisonment conditions, collective and arbitrary punishment, and regular humiliation. IPS’ overarching policy of harassment and strictures unrelated to security infringes on prisoners’ human dignity and constitutes cruel and inhuman punishment.