While celebrating the exhilarating achievements of the popular democratic uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, I have also been consumed with a restless hope and deepening concern for Iranians with parallel dreams of realizing a free and democratic society. Iranian pro-democracy activists and opposition figures Mir Hossein Moussavi and Mehdi Karroubi have called for peaceful rallies across the country today, on the 25th of Bahman (February 14), to express solidarity for the spreading democratic movements in Egypt and Tunisia, and, implicitly, to revitalize their own popular civil rights movement, known as the Green Movement. In Tehran, the planned rally is to conclude at Meydan-e Azadi (Freedom Square), the counterpart to Egypt’s Meydan al-Tahrir (Liberation Square). It is one site where millions of Iranians gathered over the six months following the rigged presidential elections of June 2009 to demand free and fair elections; accountability for government repression during the election and its aftermath, including for systematic torture, beatings, rapes and killings; the release of all political prisoners; and their full rights to freedom of speech, press, and assembly. The brutality unleashed on Iran’s popular Green Movement drove it away from street protests, but the movement’s demands are still alive and looking for opportunities to assert themselves.

.jpg) [Meydan-e Azadi, Tehran, 2009]

[Meydan-e Azadi, Tehran, 2009]

Government repression and intimidation in advance of the solidarity rallies began days ago, and is steadily progressing as the demonstrations draw near. Anti-riot police and plain clothes forces have already been deployed and are roaming the streets two by two on powerful motorbikes, equipped with guns and clubs. Mir Hossein Moussavi (Iran’s first Prime Minister and rightful winner of the 2009 presidential elections) and Mehdi Karroubi (a former Speaker of Parliament and reformist presidential candidate) are both under house arrest, and have had their landlines, cell phones, and internet access cut off. Since February 8, security forces have raided the homes of at least 30 activists and journalists, mostly in the middle of the night, and taken them to undisclosed locations. (For details about 13 missing individuals, see this list compiled by The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran — including opposition leaders and their families alongside journalists, bloggers, and student activists.) Rasoul Montajabnia, deputy secretary-general of the National Trust Party, Karroubi`s political group, was attacked and injured by unknown assailants while praying in a mosque, and Moussavi’s legal advisor has been arrested. Intelligence agents have interrogated several journalists and warned them that they are being watched. Internet speed has been drastically reduced and search engines are being blocked from searching for the word “Bahman” or accessing sites with updated information about the marches (though activists are already making new filter-busting software available). Mobile phones are being randomly disrupted, and there are reports of the government arbitrarily intimidating people by sending threating SMS text messages warning them not to participate in the rallies.

This preemptive repression of peaceful solidarity rallies by democratic forces belies the Iranian government’s public praise for the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia. While the Iranian government lauds the movements in both countries and tried to spin them as a sign of “Islamic awakening” vindicating the Islamic Republic of Iran — a claim roundly rejected by Egyptian and Tunisian demonstrators themselves — authorities have sought to limit their impact, which they correctly understand as a challenge to their autocratic power. After BBC’s Persian and Arabic services held a joint broadcast on February 9 in which Iranian and Egyptian callers exchanged views and expressed mutual interests, the Iranian government began an aggressive campaign to jam the station and all satellite coverage of Egyptian protests and ensuing celebrations.

Meanwhile, the Iranian media predictably refuses to broadcast either the political vision or composition of the democratic movements in Tunisia and Egypt, lest their pluralistic and anti-autocratic (rather than Islamist) politics — driven by students, youth, human rights activists, and a citizenry crossing class, gender, and religious divides — too clearly mirror and reinforce Iran’s internal popular opposition. When Iranian commentators on state TV are not mendaciously celebrating the Islamist nature of the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings — a spin tactic which would be mocked by their Arabic and English speaking audiences on Al-Alam and Press TV respectively — they focus on the role of U.S. imperialism, the potential impact on Palestine and Zionists policies, and the question of Egypt’s transition from military to civilian rule. Anything, in other words, to avoid addressing the fact that a heterogeneous popular uprising demanding freedom, democracy, and dignity was able to make the impossible possible by deposing the autocrat of a fully armed police state. The domestic Persian language media is more brutal; it not only refuses to broadcast the voices of Iranian opposition figures who see their goals as parallel to those of democratic movements in Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Jordan, Algeria, and beyond, but threateningly characterizes them as “seditionists,” “spies,” and “counterrevolutionaries” who should be crushed.

["Coming together to Liberate Freedom" plays on Tahrir (Liberation) Square in Cairo and Azadi (Freedom) Square in Tehran. Image from the 2009 Green Movement protests, photoshopped & circulated to invite people to the February 14, 2011 demonstrations.]

["Coming together to Liberate Freedom" plays on Tahrir (Liberation) Square in Cairo and Azadi (Freedom) Square in Tehran. Image from the 2009 Green Movement protests, photoshopped & circulated to invite people to the February 14, 2011 demonstrations.]

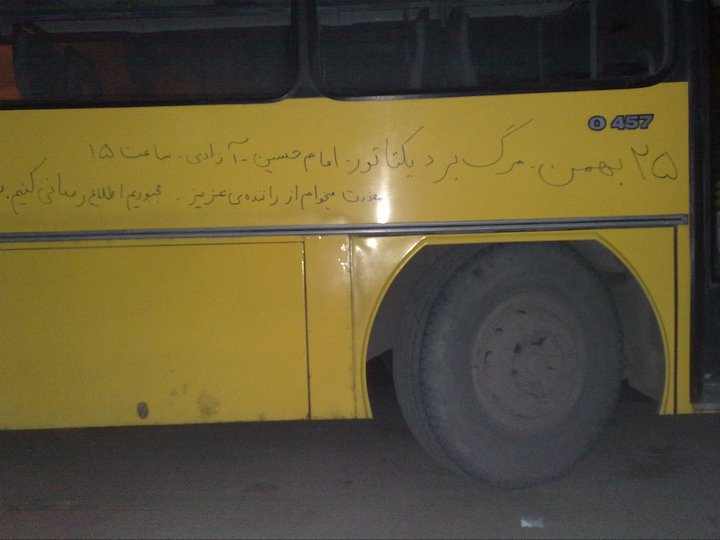

Despite growing enthusiasm from Iran’s Green Movement supporters for the solidarity rallies against autocracy on February 14, it is not yet clear whether large numbers will appear on the street. The support is unmistakable. Student groups from universities in multiple cities have supported the call to rally, as have labor groups, professors, and dissident religious authorities. Isa Saharkhiz, the eminent journalist who has been imprisoned since the summer of 2009, sent a statement from prison supporting the call to march. Moving support has also come from quarters such as a group of political activists released from the notorious Evin prison in Tehran and the “Mourning Mothers of Laleh Park,” a group formed by mothers whose children were killed or disappeared in the repression following the 2009 elections. (These mothers seeking accountability for the fate of their children have been subject to arrest and are no longer being allowed to hold their vigils in Tehran’s Laleh Park. They recently sent a message of solidarity to Tunisan and Egytian mothers whose children were killed.) Political prisoners in Rejaee Shahr Prison in Karaj have begun a hunger strike in support of the protesters. Support has also been spreading and escalating on social media sites, and visible in graffiti hurriedly scrawled on city streets and buses, along with messages being passed on monetary bills.

["25th of Bahman, Down with the Dictator, Imam Hussein to Azadi Sqare at 3pm...My apologies to the dear bus driver, we have to spread the word!"]

["25th of Bahman, Down with the Dictator, Imam Hussein to Azadi Sqare at 3pm...My apologies to the dear bus driver, we have to spread the word!"]

["25th of Bahman — Our Day of Anger!"]

["25th of Bahman — Our Day of Anger!"]

The uncertainty about whether the call to rally will translate into bodies in the streets rests in the possibility that the state will produce a show of force great enough to prevent any gathering, and the brutality that the Iranian people have suffered since they took to the streets by the millions in 2009. It is hard to describe or grasp the impact of mass arrests and killings, and of systematic rape and torture in prisons used to extract false confessions and terrorize dissidents. Or of the televised collective show trials and morning TV programs that showed leading opposition political figures, seasoned activists, and journalists clearly tortured into recanting and declaring their allegiance to the government. In one particularly nauseating case, a political prisoner was tortured into publically expressing his affection for his interrogators and prison guards. This is to say nothing of the ongoing risk protesters face of being punished with permanent expulsions from their jobs and schools, effectively incapacitating them from supporting themselves and their families and ending their careers as students or professionals.

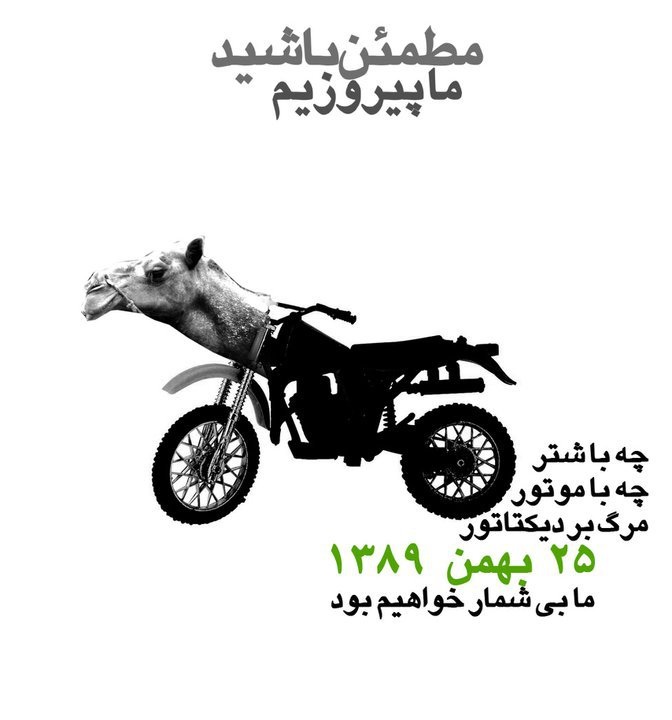

["Be Certain: We Shall Be Victorious. Whether by (Mubarak`s) camels or (the Basij`s) motorcycles, down with the dictator. Bahman 25, 1389. We shall be innumerable."]

These risks are particularly difficult to bear in Iran given real fears that there might not be anything to stop the Iranian government from using its monopoly of force in a blood bath to crush dissidents. In Egypt, the political costs of a blood bath were ultimately too much for the Mubarak regime and its U.S. backers to bear, and Hosni Mubarak was forced to step down rather than have his security forces fire indiscriminately into Tahrir Square, presuming enough of them were willing to do so in the first place. This is not to underestimate the real violence suffered by the Egyptian people: conservative reports calculate that at least 300 Egyptians were killed and thousands injured. But there is a real concern that whatever balance of forces and political costs prevented the governments in Egypt and Tunisia from simply killings thousands of people may not exist in Iran, where the legitimacy of the state has shrunk to an all-time low and governance increasingly relies on force rather than consent or any pretense of liberality. In a joint statement released in advance of the rallies, Moussavi and Karroubi called on the army and police to side with the people and not use violence against them, but the Iranian regime, however unpopular, still appears to have a clear monopoly of force.

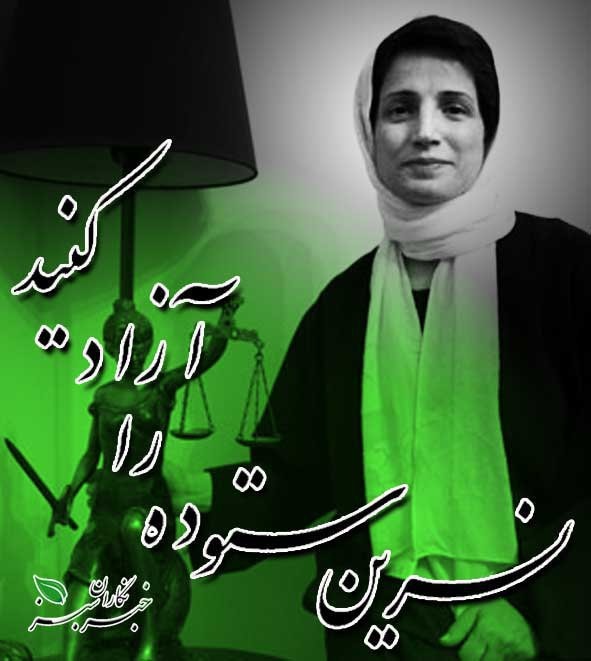

To further clarify the role of terror and violence in the Iranian government’s rule, it should be said that the Iranian state is second only to China in its rate of executions. In 2010 the Iranian state executed at least 542 people, and in January 2011 alone, executions spiked and at least 83 people were killed. Only a day after the electric January 28 protests in Egypt which analysts called the “tipping point” leading to Mubarak’s fall, the Iranian government executed a woman named Zahra Bahrami after having tortured her. Ms. Bahrami had been arrested after participating in the massive and peaceful December 27, 2009 protests, and not even her dual Dutch-Iranian citizenship could save her. On the contrary, the brazen execution of a European woman can be read as the Iranian government’s demonstration of its repressive force and consolidation of its rule as an increasingly isolated state. Before Ms. Bahrami was executed, her attorney Nasrin Sotoudeh — the prominent human rights attorney who represents protesters, dissidents, and juvenile offenders facing the death penalty — was herself imprisoned.

["Free Nasrin Sotoudeh"]

On January 10, 2011, Nasrin Sotoudeh was sentenced to eleven years in prison, and barred from practicing law for twenty years from the day she is released, effectively ending her capacity to ever work again. Ms. Sotoudeh’s own lawyer has also been threatened with arrest for defending her. There are too many names and lists of prisoners, including this one of women human rights activists and journalists; we should try to learn each name and each story, and match them to faces when possible to make sure they are not forgotten. Every Iranian was floored when just this past December two Iranian filmmakers, including the internationally renowned Jafar Panahi, were sentenced to six years in prison for “propaganda against the regime” and banned from filmmaking for twenty years. On the 32nd anniversary of the Iranian revolution, which also marked Mubarak’s ouster, Jafar Panahi’s heart-wrenching open letter was read to the Berlin International Film Festival, where he had been invited to serve on this year`s international jury. Make no mistake, Iranians are not inured to these injustices simply because they are so numerous.

The critical question in light of all this remains: What should ethical solidarity with Iranians struggling for justice and a meaningful democracy look like? What is our responsibility to them as people abroad or in the diaspora as they attempt to rally in solidarity with regional movements for freedom, and against their own oppression?

I think we must first take notice of the gravity of the Iranian people’s aspirations, and value their dreams for a life of dignity and freedom, regardless of whether they make it out to the streets today in large numbers, get back into the front pages of the presses, or whether they are pushed back by the violence of the state. (Note that the foreign media was expelled from Iran in the early aftermath of the 2009 elections and banned from contacting opposition figures, so international audiences could not hear voices of Iran’s popular uprising with anything resembling the proximity of what they heard from the popular uprising in Egypt. The international press remains out and unable to document the tribulations of the Green Movement today.)

Far too many nominally Left intellectuals and activists have withheld their solidarity from Iran’s popular Green Movement, baselessly dismissing it as an elite movement against a government serving the working poor and standing against Israeli and American imperialism. Iran’s Green Movement has a broad social base that cuts across class, religious, gender, and urban vs. rural divides, and has support far beyond the capital. It has deep roots and must be understood against a longer backdrop of civic engagement and seasoned social movements – led particularly by women, students, and labor. As for President Ahmadinejad’s government, with the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s support, it has cracked down on labor unions, arrested labor leaders, and repressed mass actions by bus drivers, sugarcane workers, oil workers, and teachers. It has changed labor laws against labor and for capital, and privatized more thoroughly than any post-revolutionary government, redistributing wealth towards the military-intelligence establishment. As for its anti-imperialism, as one scholar appropriately quipped: National Socialism was also a type of socialism, but it was a socialism for fools. Similarly, Ahmadinejad’s anti-imperialism is an anti-imperialism for fools. More generously, while those not familiar with Ahmadinejad’s repressive policies domestically might understandably admire his government for seemingly resisting U.S. and Israeli might, particularly in Palestine, a closer inspection should reveal that his oppressive government is not one to model or wish upon others, and that like so many other autocratic governments in the region, only opportunistically uses the real injustices against the Palestinian people to bolster its own interests.

Those who are more likely to sympathize with Iran’s Green Movement must remember that despite the repression Iranians are up against, they are not victims who need to be “saved,” but agents in a just movement of their own making, who deserve our attention, understanding, and support. As we monitor and draw attention to the Iranian government’s crimes against its people and its egregious human rights abuses, we must simultaneously remember to loudly voice our opposition to proposals for war and sanctions against Iran, which internationally come from figures across the political spectrum, and must be rejected regardless of whether they are offered with “good intentions” or made opportunistically to forward particular political agendas. War and sanctions, which are not only a prelude to war but war by other means, have only served to hurt the Iranian people and cripple their aspirations.

It must be remembered that despite the pretty speeches by the Obama administration, the quest for hegemony is a driving force for U.S. foreign policy, and that the Iranian government, however vile, is an annoyance to the American political elite not because of its human rights violations, but because it represents the failure of full (if shifting) U.S. hegemony in the region. Both historically and in the present the United States has preferred pliant autocratic allies in the region over troublesome democracies whose aspirations are likely to conflict with that of the U.S. political elite. It is no wonder then that countries like Egypt (under Mubarak) and Saudi Arabia – not democracies by any stretch of the imagination – have been U.S. allies and large recipients of U.S. aid. It is also well known that the United States has not supported democratic movements in the region; on the contrary, it has a long history of backing repressive but compliant movements and states. The Obama administration has not had the same bellicose posture towards Iran as the Bush administration, and at the final hour it has rhetorically embraced the democratic movement in Egypt, but its different strategy of governance should not be imagined to mark a fundamental break with the strategic goals of American power.

Given the U.S. government’s lack of moral political legitimacy, and its anti-democratic interests in the Middle East and beyond, its public assertion of support for Iranians planning to demonstrate today is less than useful and can help the Iranian government punish them as unpatriotic agents of the United States. Effective solidarity cannot come from the U.S. government, but from progressive forces in the Middle East, the United States, and wherever genuine solidarity with Iran’s democratic Green Movement exists. As the Iranian government attempts to spin and co-opt the democratic uprisings in the Middle East, voices from the region or linked to movements there can play a particularly effective role in preventing the Iranian government from brutalizing its own people rather than meeting their demands.

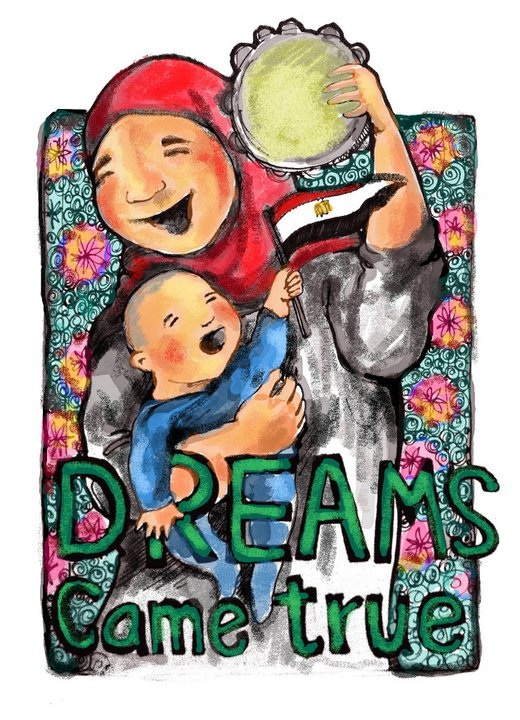

Wael Ghonim, the Egyptian activist hailed in his country and around the world for his role in the Egyptian uprising, was approached by an Iranian human rights group. When asked if he wore his green wristband in solidarity with Iran`s Green Movement, as many Iranians watching him on TV and the internet had excitedly hoped, Wael responded that no, it was just a coincidence, but one that he was happy about. He offered words of encouagement to the Iranian people on the eve of their planned demonstrations, and said that they should learn from the Egyptians, as the Egyptians had learned from them, that in the end the power of the people will prevail. "If we unite our goals, if we believe," he said, "then all our dreams can come true." Soon after, the "We Are All Khaled Said" Facebook page, which Wael Ghonim helps administer and which played a critical part in galvanizing the Egyptian movement, displayed as its profile picture a painting by the Iranian activist and artist with the pseudonym Termeh (see below).

Voices like Wael’s, along with those belonging to readers committed to a future without torturing and anti-democratic states, can at this juncture play an invaluable role in supporting Iranians standing up for their freedom, in solidarity with their counterparts in Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Algeria, Jordan and beyond. I hope you will raise your own voice in unison, and encourage others to do the same, well beyond today.

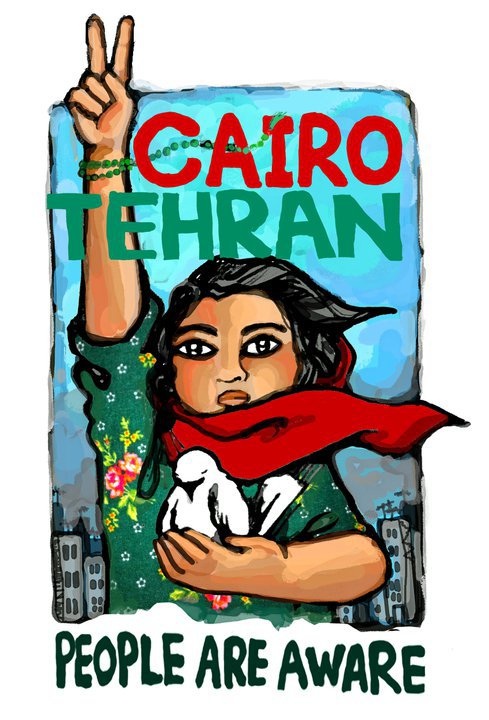

[Two Iranian-Egyptian solidarity posters: the one on the left cites a poem by the great 14th century Iranian poet Hafez-e Shirazi; the one on the right is by Iranian artist and activist Termeh.]

Postscript: Developments are unfolding rapidly as of this writing. See Tehranbureau`s "Iran Live Blog: 25 Bahman/14 February" for ongoing updates.