We are living in extraordinary times. 2011 Egypt, in hindsight, will be seen as just as, if not more, “historic” as the 1952 coup. This precedent and others illustrate that this revolution is not the instantiation of the political awakening of a “stagnant” part of the world, and nor was it brought to you (only) by Facebook or twitter. For now, the 2011 people’s uprisings in Egypt and in Tunisia resist categorization, and cannot be contained or explained by adjectives that Middle East “experts” have used to shape the dominant discourse on the Arab world such as "Islamist," "communist", "liberal", "pro-American", "anti-American", "fundamentalist", or "feminist." We should cherish these moments of discursive resistance because they paint an image of life as it is lived, messy and contradictory.

The urge to draw conclusions and make predictions (the urge to make meaning, as it were) is seductive. On Al-Jazeera and in the New York Times, experts are playing the game of which Arab authoritarian ruler or regime is next. While the importance of the ousting of Mubarak in Egypt and of Ben Ali in Tunisia cannot be overstated[1], neither can it be assumed that 1) these two revolutions follow the same model or that 2) this model can be copy pasted into the rest of the Arab world. Egypt and Tunisia will not create struggles, but they will greatly invigorate the protests, oppositions and resistances that citizens have been practicing for years in places like Yemen, Syria, Bahrain or Jordan. These citizens, like their comrades in Tunisia and Egypt, have also been violently repressed for years because of their political resistance. While there is a possibility of a “contagion effect” influencing the region, in this post I would like to question where Lebanon stands in this analysis.

Because revolution fever has caught the attention of the world, the political situation in Lebanon and the workings of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, which had previously dominated so much international media attention, has been receiving little coverage lately.[2] The tribunal will be publicizing its indictment in the assassination of Rafik al Hariri in the coming weeks, if not, as leaks suggest, earlier. This international court has polarized Lebanese political discourse since February 14, 2005, when Lebanese politicians and citizens began demanding “justice” for assassinated leaders and the citizens who died with them. Most recently, the Sunni Muslim religious institution in Lebanon, Dar al-Fatwa, released a statement at the behest of the Mufti of the republic which equated respect for the international tribunal with respect for the Lebanese Sunni Muslim sect as a whole. This statement was published following a meeting housed at Dar al Fatwa between the country’s Sunni political leadership, including former and current Prime Ministers Fuad Sanioura, Saad al-Hariri, and Najib Miqati. As the political discourse of the Hariri-led March 14 coalition and the Hezbollah-led March 8 coalition escalates, Lebanon anxiously waits for the indictment to be publicized and for the formation of a new government by PM Miqati. Faced with a paralyzed government, high unemployment and higher underemployment, eroding infrastructure and public works, and the crippling underfunding of national institutions such as the public school system and national healthcare, it would seem logical for Lebanese citizens to stand up and demand responsible and effective leadership. One would expect Lebanese citizens, said to be among the most online Arab populations and the most freedom loving (to paraphrase George W. Bush), to demand an end to the five year stalemate during which successive governments failed at basic tasks and during which corruption continued to be the status quo among political elites. But despite the arguments of many journalists and Lebanese nationalists, what happened in Egypt or Tunisia cannot be repeated in Lebanon. The factors contributing to the unlikeliness of a popular revolution in Lebanon can be roughly grouped under the headings 1) Domestic political environment, 2) Statecraft, 3) Geopolitical position, and 3) State institutions.

1) Both the March 14 and March 8 political coalitions are mass based popular movements. The strong support enjoyed by both political camps was evident in the 2009 Parliamentary elections, when March 8 won the overall popular vote but March 14 won the most parliamentary seats. This split electoral result is due to the ways that elections are held in Lebanon; all Lebanese citizens vote but they vote only in (and for) their districts. Each district has a set number of candidates who are supposed to reflect the “sectarian makeup” of that district. Therefore, while a simple majority of Lebanese citizens voted for March 8 candidates, March 14 won the election because the number of seats allocated to districts does not always correspond to demography, and because there was higher voter turnout in pro- March 8 districts. Simply put, more March 8 supporters voted in the 2009 elections, demonstrating their desire to participate in democratic elections. Many Lebanese journalists and much of international media neglect the fact that a large number of Lebanese citizens support both coalitions. In fact, for these journalists, Lebanese citizens who support March 14 do so out of a democratic spirit while those who support March 8 do so out of sectarian affiliations born out of either primordial affiliations or a lesser-evolved political consciousness. In 2005, the year that witnessed the assassination of Rafik al-Hariri and the birth of the current political impasse in Lebanon, both the March 14 and March 8 camps were able to mobilize massive amounts of citizens who protested for “their [political] team.” Again, while international media focused on the well-dressed and "life loving"[3] March 14 protestors, the hundreds of thousands of citizens who came to the March 8 protests were treated with skepticism, if not hostility, by both domestic and international media.

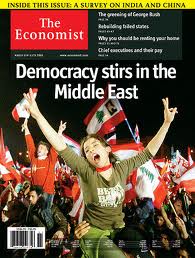

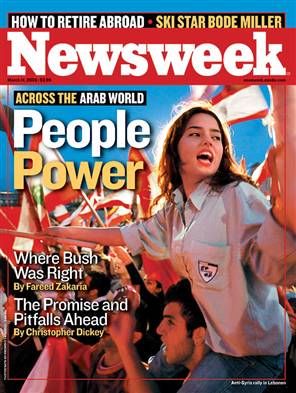

[March 14 Protest; Image from The Economist] [March 8 Protest; Image from Life Magazine]

2) Despite the ways in which March 8 is painted as an anti-democratic coalition and despite the fact that this supposedly anti-democratic coalition now holds the majority in government, Lebanon is not, and it never has been, an authoritarian state. Lebanon is a parliamentary democracy structured according to the principle of power-sharing between sects. It has a functional constitution, a system of checks and balances, an active judiciary, and holds regular parliamentary elections that witness fierce competition between political rivals. What partisan journalists and Saad al-Hariri have called a “Hezbollah coup” or hostile takeover was in fact a politico-legal process outlined in the Lebanese constitution. While the system of political sectarianism defines much (and erodes much) of political life in Lebanon, the fact that Lebanon has fairly functional democratic institutions cannot be denied. Lebanon also enjoys a relatively free press. In fact Lebanon’s status as a relatively liberal parliamentary democracy may be a factor in stymying the revolutionary fervor of its citizens, who generally feel less oppressed (although they may be just as powerless vis-à-vis any government once it is elected) than their Arab neighbors.

[Tai`f` Logic: Shiite President of Parliament, Maronite President of the Republic, Sunnite Prime Minister; Image from unknown archive]

3) A third reason why Lebanon is not on the way to becoming another Egypt or Tunisia is that, despite what many Lebanese nationalists may think, Lebanon is not a very geopolitically important state in the Arab world. It has no real influence in terms of foreign policy (no one is waiting to see what the Lebanese President or Prime Minister has to say about situation in Tunisia, for example).[4] Also, it is not considered a regional power broker. Instead, the Lebanese state has relied on regional brokers to maintain itself throughout its history. Lebanon has no natural resources (save water), its economy is not large, and it has a very small population. Its four million citizens represent roughly 1/5 of the residents of Greater Cairo. Furthermore, the investment by international powers in Lebanon has been much more varied than it has been in Egypt, where the United States has underwritten the Mubarak regime for 30 years. In Lebanon, different power configurations come into play, different international powers exert different pressures, and the interests of states such as the US, France, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Iran change, wax, and wane according to the political winds. In fact, in Lebanon different regional and international powers may fund different factions of Lebanese politics, such as the Saudi Arabian government’s bankrolling of the Hariri’s Future political party and Iran’s similar funding of Hezbollah. Unlike Egypt, Lebanon is not the recipient of consistent foreign aid and it never has been, in part because Lebanon has been in a state of war with Israel since 1948, and it is currently the only non-Palestinian “hot border” in the ongoing Arab Israeli conflict.

4) The state does not enjoy hegemony over the use of violence in Lebanon, and its coercive capacities are weak, unlike in both Egypt and Tunisia. While there have been recent attempts to bulk up both the army and the internal security services in a bid to counter Hezbollah’s military strength, the institutions of the army, the police, and the security services play very different roles in Lebanon than they do in most of the Arab world. They are relatively small institutions that have little influence on state policy but have in recent years played an important and impartial role during times of civil strife. Lebanon is not an authoritarian state that must rely on force to sustain an unpopular regime. Furthermore, Hezbollah’s militia is better trained and equipped than the Lebanese army and has been much more effective at defending Lebanon’s southern border against Israeli encroachment and occupation. Still, the Lebanese army is perhaps the most respected national institution, and under the tenure of President Emile Lahoud, it was largely de-sectarianized[5]. The importance of this reform of the army cannot be overstated, and these reforms’ effectiveness have caused much anxiety for politicians such as outgoing Minister of Defense Elias al-Murr, as evidenced by his conversations with US embassy officials where he expressed his unease with the fact that more and more Muslims, and in particular Shiite Muslims, were joining the armed forces. Unlike Egypt or Tunisia, the population is heavily armed due to memories and practices of past civil wars and due to constant fears of a new one.

[Lebanese Army; Image from Now Lebanon]

Taken together, these facts demonstrate that that unlike Egypt and unlike Tunisia, in Lebanon there is no symbol of oppression that a majority of the population can coalesce against. The majority of Lebanese citizens do not see the army, the security forces, the state, Hezbollah and even the system of political sectarianism as oppressive institutions that need to be overthrown. In the case of political sectarianism, even if there are large numbers of citizens who do desire change, they want to do so through reform, not revolution.[6] Instead, different coalitions within the population support “their” leaders against each other. This is not a recipe for revolution; it is a recipe for civil strife and perhaps even civil war. The political divide between March 8 and March 14 is so pervasive that it colors all political issues in Lebanon, including those that should be understood as non-partisan, such as the price of electricity and the failure to pay public school teachers enough, and on time. In fact, the largest non-partisan protest in recent memory was the Laique Pride March last April, but in order to be attract the 3,000 or so citizens who participated in it, organizers were intentionally vague about their stances on all political issues other than a desire for a “secular state,” to be achieved at some undefined point in the future.

[Laique Pride March, Beirut 2010; Image from unknown archive]

Eight years ago, the Arab world was supposed to be jolted out of their stagnation and into democracy by the “shock” and “awe” of the US invasion of Iraq. Two years later, the extremely photogenic “Beirut Spring” was attributed, in part, to the “active” US support for democracy in the Middle East.

[March 14 Protest; Image from Newsweek]

In fact from 2005-2008, mass protests that pitted hundreds of thousands of Lebanese citizens against each other were the norm. In 2006, during the Israel-Lebanon war of 2006, then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice described the destruction and violence wrought on Lebanon as “the birth pangs” of a new Middle East. Despite, or perhaps because of aggressive US encroachment in the region following the War on Terror, the one lesson that observers can draw from a comparative analysis of the ousting of governments and dictators in Lebanon, Tunisia and Egypt is that the influence of the United States (and its allies) is waning throughout the Arab world. Three United States’ allies, Ben Ali, Mubarak, and Saad al-Hariri, have been forced out of power in the past month. These were the “good Arabs”, posed against the intolerant, anti-American Islamic fundamentalists that were sure to take over in their stead. In Tunisia and in Lebanon (for different reasons) that didn’t happen, and it is not likely that it will happen in Egypt.

I was at a block party last weekend celebrating the Egyptian revolution. In an area of Queens known as “little Egypt”, hundreds of us were chanting, dancing, laughing and congratulating each other. One of the chants that proved popular with the crowd lists the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions as only two in a series that are bound to come within a larger Arab revolution; Thawra thawra misriyya, thawra thawra souriyya, thawra thawra ordonia, thawra thawra lubnania, thawra thawra arabiyya. In February of 2005 I had heard a similar, but radically different chant. I was at the March 14 protest (I had also been at the February 21 protest and the March 8 protest) when a group of youth activists took the stage and began listing all the groups of people who were there. They did not list political parties, or activist groups, or even coalitions for popular causes. Instead, these youth leaders, some of them younger than myself at the time, were praising the diversity of the protest by sending out “shout outs” to the Shiites, the Sunnites, the Druzes, the Maronites, and the Greek Orthodox Lebanese. I noticed, after the first couple of rounds, that members of the crowd were trying to “out-clap” each other. What began as a an attempt to show Lebanese “diversity” through categorizing citizens by sectarian affiliation ended up revealing the protest to be an arena for the competitive sport of Lebanese demographic obsession and bravado. In Queens last week, I wanted to shout “thawra thawra lubnaniyya” with my comrades, but as the words left my chest they felt hollow because in Lebanon, our most pervasive oppressor is not a dictator, or the police, or the army, or the United States, or even Israel. Instead, there will be no revolution until we revolt against ourselves. And I hope to see that revolution in my lifetime.

[1] A quarter of the entire population of people that are categorized as “Arabs” live in Egypt, and 2/3 of all Arabs live in Africa. Despite these numbers, there has been scarce coverage and analysis about how the revolutions in Egypt and in Tunisia are also African events.

[2] Another event that had received much international attention but has since been swept under the table was the referendum on the secession of South Sudan, the results of which (98% in favor of independence) were published on February 7th of this year.

[3] March 14th’s slogan at the time was the seemingly vacuous, but actually packed with meaning “I Love Life” campaign

[4] Although, in an illustration of how political leadership is not always state-centered in Lebanon, people may have waited to hear Hassan Nasrallah’s statement on the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions.

[5] Under the Ta’if Accord, the army was supposed to be reformed into a national institution by removing all sectarian quotas within its ranks. Under President Lahoud the reform of the army also included mixing all army units, stations and brigades to ensure sectarian and regional heterogeneity. However, because the Ta’if Accord has yet to be implemented fully by any Lebanese government since 1989, the Presidency of the Army is still reserved for a member of the Maronite sect.

[6] In fact a Facebook group formed in recent days urges the end of political sectarianism, but as of yet the members of the group have not agreed on how, and in what way, to do it.