The Revolutionary Socialists Movement launched its new website on 7 August. The site represents a qualitative change in our propaganda work, but it also presents some major challenges to the membership of the movement as a whole and not only to the comrades in the media committee alone. It is a necessity to provide content on an organized basis for publication, for comrades to continue to act as correspondents for the site, and to extend this correspondence with written reports, pictures, videos, and artistic works (cartoons, stencils, comics). Correspondence with the site is not a luxury or only the responsibility of the small number of comrades who run the site, but it should continue to be the task of the largest possible number of comrades in the movement, if not all of them.

The site is still in an experimental stage, and there are a number of technical problems and tasks which are not finished. The technical team is working on solving or completing them and developing the site to move to the next phase of the project, which includes the establishment of a special multimedia section and a discussion forum for members of the movement.

The transition to the next phase of the site may take several months, as the challenge before us is not just technical, but also political and organizational, as the site will not be able to raise its performance and take on the role it should play without reorganizing the ranks of the movement to serve this new approach to revolutionary work. To clarify this, let us go back a little and give some background on this issue.

A number of well-known comrades from the movement have ben present in the citizen-journalism (blogging) movement since 2005 and the youth of the Revolutionary Socialists (RS) have made increasing use of "alternative media" tools since 2008. However, they generally took individual initiatives and the movement did not have a general strategy for dealing with the internet and social networks which were spreading, although there was a degree of organizational coordination between the RS labor organizers and the movement’s bloggers over the Mahalla strike of September 2007, the Mahalla uprising of April 2008, and the tax-collectors’ sit-in in December 2007, a battle which led to their formation of the first independent union in Egypt since 1957.

The launch of the old site (www.e-socialists.net) on 6 April 2009, the first anniversary of the Mahalla uprising, was a step forward, because for the first time in the movement’s history, a committee was formed to manage the site and organize propaganda work on the internet. At the time, the site provided a good opportunity, to the extent available at the time, to spread our ideas on the internet, provide an archive of literature, win a number of young people to the movement and its ideas, and develop some initiatives and activities which were happening on an individual level and link them to the general orientation of the movement.

However, there were many problems and shortcomings in the work of the group, such as:

- The site was often an isolated island and the members of the site team had to “hunt down” comrades in order to get reports from them, which often appeared late or did not even make it onto the site.

- The old site was not able to highlight audiovisual content such as photos and videos.

- Despite the rich content of the site, it was difficult for the visitor to browse or find the desired material because of its complexity and the poor organization of its sections.

- The site suffered a number of technical problems because of its irregular maintenance and development, and it kept collapsing under the volume of visits.

- The focus was on the official website, and there was no clear plan for propaganda on the social networks such as Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, Scribd, Diigo, and YouTube, despite the establishment of official accounts for the movement on them.

These problems also had a political nature:

- The design of the site with a single large photo in the center with no other visual content highlighted in the form of images, videos, and the design highlighted written content in the form of columns; this reflected the traditional political outlook on the nature of the site, which was that it was no more than an online companion for the content of the print edition of the Socialist newspaper, which at that time appeared monthly.

- The lack of interest that comrades in the movement had in acting as correspondents for the site did not only reflect the fact that the site was badly-designed or difficult to browse, but it also had political roots, which can be summarized in the lack of political awareness of the political task that a website must play in a revolutionary movement—that of an organizer.

Lenin’s book What is to be done? represents the theoretical basis for building Marxist organizations from the last century. In this book, Lenin tries to answer the question that was facing revolutionaries in Russia at the time, and that faces revolutionaries in Egypt today and at any time: how can we build our organization? How can we transform coordination between groups of geographically-dispersed revolutionaries? How can we ensure unity and centralism in reality, and at the same time, create channels of democratic debate between revolutionaries?

Lenin’s answer at the time was a revolutionary newspaper. Every member of the revolutionary organization was also a reporter for the revolutionary newspaper, and their job was to supply the newspaper with reports. But how were these reports produced? The revolutionary correspondent would get involved in any struggle or activity where he lived or worked, and follow these with reports sent to the newspaper, so that this experience would be generalized to all the comrades who read them in other sectors and areas, and the newspaper would create an opportunity for him to connect with this audience and to engage them in his issue.

When you read a report about a factory in an issue of The Socialist, it means that a comrade went to the factory, interacted with the workers and created links with them, and then returned with the report. The process of journalism is a process of organization. It is easy for anyone to sit in the office, browse the net, and write a news story about the factory, but this is not the kind of journalism we want. Sending a report to the paper means that you are engaged on the ground at the same time as you are connected to the rest of the members of the movement, and that you are engaged through the channel which is open between you and the editorial board of the newspaper.

The revolutionary correspondent is not “impartial” and does not pretend to be. The revolutionary correspondent is biased—in favor of the workers in their struggle with management and in favor of the masses in any battle with the authorities. But this does not mean biased in the sense of lies and exaggeration. That is the task of the bourgeois media, not the revolutionary. Sometimes, unfortunately, we see some activist journalists who exaggerate the size of demonstrations so that a demonstration of twenty workers suddenly becomes two thousand, or a defeat of workers in a strike is reported as a victory. The people who do this think mistakenly that they are helping the workers and that this will raise their spirits. But in reality, they are misinforming their audience and their exaggerations could be easily debunked, leading to a loss of credibility.

The organizing revolutionary newspaper, as Lenin explains, plays a role in unifying the stances of the members of the movement in different parts of the country. So a revolutionary socialist, in any place in Egypt, from Alexandria to Aswan, can see through the newspaper the official position of the movement on this issue or that.

But when Lenin wrote these words at the beginning of the twentieth century, news traveled from city to city by postmen on horseback. Even in 1917, when the Russian Revolution broke out, news of the revolution in Petrograd and Moscow could take weeks or sometimes months to reach the rest of the Russian empire.

The situation is different today. News travels at lightning speed, not only inside the country, but even between the five continents of the world. Over the internet and satellite channels it is possible to sit in Cairo and follow news of the Tunisian revolution minute by minute. You can be in Alexandria and connect with British clerical workers having a sit-in at their office in a small town in Scotland over Twitter and Facebook. You can be in Assuit and follow the demonstrations of the Spanish miners via live-streaming over the internet.

The development of the communications sector in Egypt is a glaring example of the “uneven and combined development” of capitalism that Trotsky talked about.

[A brick factory worker in Meit Ghamr has his mobile phone hanging from his turban during the work shift. Photo by Mohamed Ali Eddin, from www.arabawy.org]

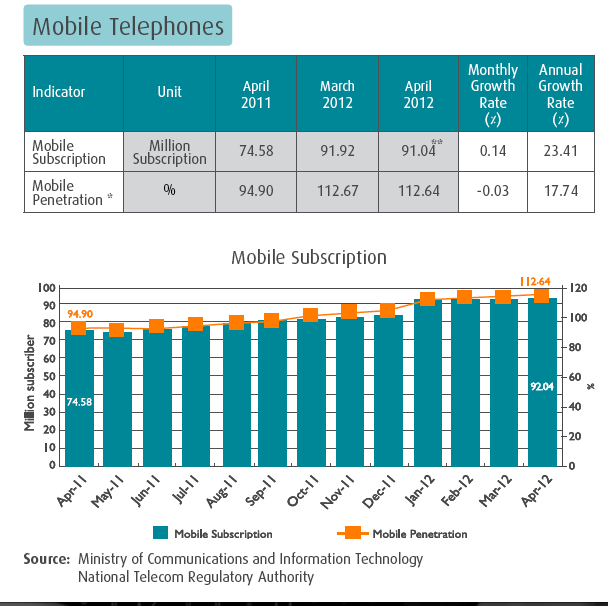

In a country that has a population of around ninety million, in which forty percent of them live below the poverty line, the number of mobile phone subscribers in Egypt has reached ninety-two million—saturation surpassing one-hundred percent of the population, according to the latest report from the Ministry of Communications this May.

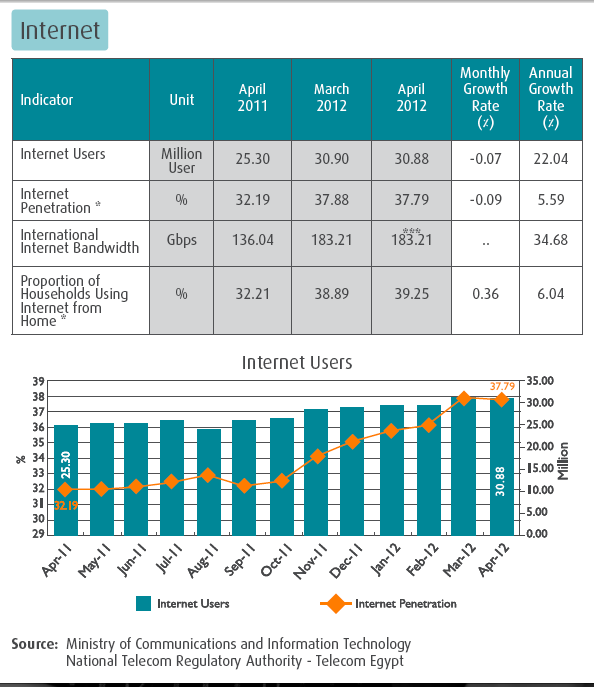

According to the same report, the number of internet users has risen to roughly thirty-one million.

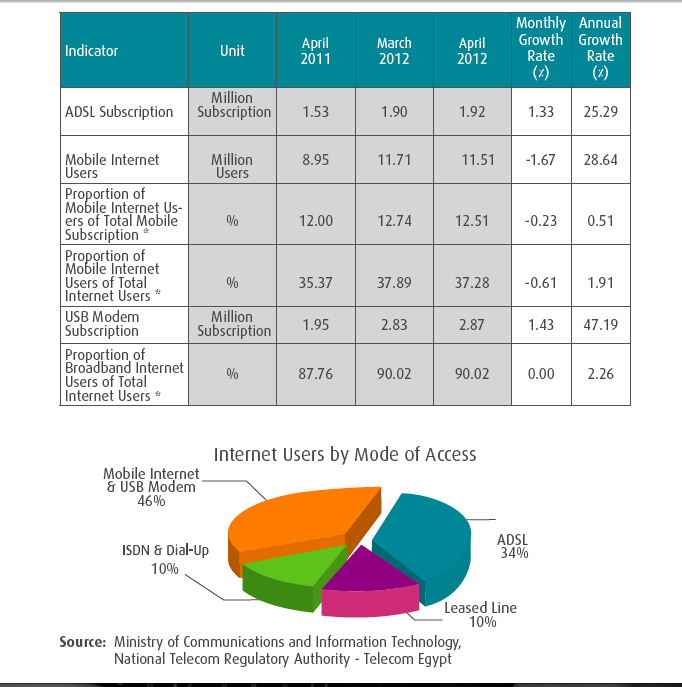

It is very interesting to observe the relative distribution of internet users, for we find that the lion’s share of them get online via mobile phones and USB modems, which are constantly falling in price.

The spread of this method of access is progressively enabling social classes beyond the bourgeoisie and the middle class to get online. It is this segment of users that is most likely to increase at a rate surpassing the other sectors.

The tempo of work in every revolutionary movement is set to a large extent by the central organizer. In the 1990s, the newspaper Revolutionary Socialism was the organizer for the movement, and it appeared monthly. This was appropriate to the low level of class struggle, and was also reflected in the small size of the Revolutionary Socialists movement. Today, if we consider the website as the organizer, it means that we must update this site minute by minute, and follow political events and activities that occur in Egypt before any traditional source of expertise. The arrival of reports and updates for the site around the clock translates organizationally into the presence of revolutionary correspondents on the ground getting involved with events and then sending a report to the “center,” which is the site editorial board that establishes, in turn, a faster rhythm of organizational work.

For example, if Al-Masry Al-Youm publishes a news story about a strike in a factory in Mansoura and this does not appear on our site, then we need to ask ourselves why not? If the Revolutionary Socialists have any presence there or connection with the factory, then why did they not send the news immediately to the site? It is just as critical for a worker (who is, in these circumstances, a revolutionary correspondent), to contact the site to spread the vital news of the strike as it is to build barricades to defend the sit-in. Contacting the site at this moment means that the revolutionary worker correspondent is included in a communication network, and the experience of what he does in Mansoura is disseminated immediately to the rest of the members of the movement, as well as all militants interested workers’ struggle. This means they are always ready to offer solidarity and coordinate what they are doing in their own areas with what their comrades are doing in Mansoura.

This once again gives a tremendous push to the acceleration of the rhythm of communication between the different sections of the movement. The presence of revolutionary correspondents on the ground in every province, tasked with supplying the site with constant reports, and accountable when we hear news from their areas via the traditional media rather than from them, means that there are activists on the ground, assigned at all times to throw themselves into events that are happening, and under constant pressure to expand the network of revolutionary correspondents in their provinces, which translates into gains for the membership of the movement.

Suppose a military coup took place today. Would revolutionary socialist cadres across Egypt wait for two or three weeks until the paper appeared to know our position? Or would the leadership of the movement phone and travel to meet each comrade to tell them the line? Here we return to the role of the site as organizer. It is obvious that the site will offer a quick way to connect and announce the official position to members of the movement in different provinces on this or that issue, which requires a rapid, unified reaction.

Newspaper journalists care about written content, but comrades who are correspondents for the site should pay special attention to audio-visual content alongside written reports about the events they are involved in. Photographs and videos are not a luxury, as it is the duty of every comrade involved in a event to make efforts to take photographs or film on a mobile phone. In general, the movement must pay special attention to passing on skills in photography and training in the secure use of email and social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, to as much of the membership as possible.

The site will not be a substitute for the paper, and comrades must continue in the hard work of distributing the paper at events, to the network of members, and to sympathizers. Despite the increasing numbers of workers using the internet (whether via mobile, a link at home, or in cyber-cafés), the paper will continue to be an essential means to interact with them. We must do our best to ensure that it is published regularly, but the paper will be a complementary, rather than a central, organizing publication. It may be that the adoption of the website as an organizer is the first step towards the modern answer to the same question posed by Lenin in the last century: what is to be done?

[This article was originally published on 3arabawy.]