The basic Algerian tripartite configuration of a national gendarmerie, the police, and the armed forces (army, navy, air force) mirrors in many ways its French counterparts. As with the French national Gendarmerie, the Algerian equivalent, made up of 150,000 people, serves as a paramilitary force charged with public safety and policing among the civilian population especially outside urban areas. Additional core tasks include counter-terrorism patrols and searches in the countryside as well as urban crowd and riot control units for each of Algeria forty-eight administrative wilaya. Gendarmerie duties overlap with those of a police force of 200,000 whose specialized anti-riot troops control entry into and within the capital Algiers, thereby more than doubling the numbers of uniformed personnel deployed in Algerian cities against protests, marches, and uprisings.

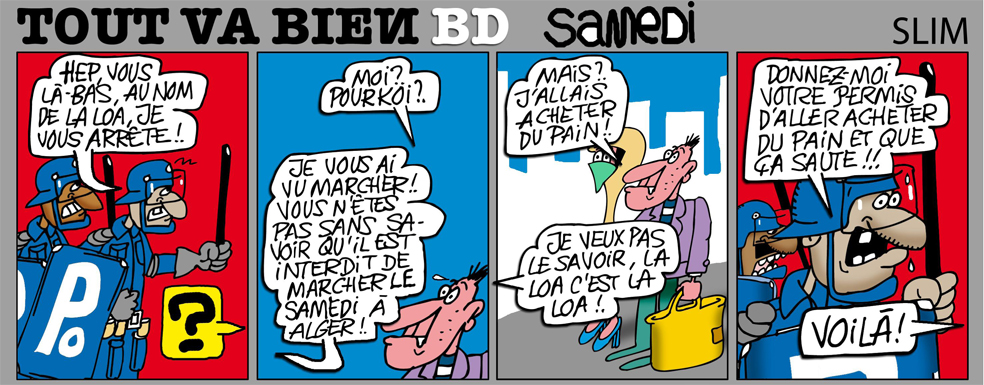

In 1992, a coup d’etat removed President Chadli Benjedid from office and brought about nineteen years of a “state of emergency.” Consequently, Algeria adopted a comprehensive model of counterinsurgency against armed Islamist groups that was a paradigm of hegemonic control: Gendarmerie roadblocks and checkpoints proliferated throughout the country to play a double-edged role as possible deterrents to terrorism but also as an effective means to harass and shakedown the population. On February 24, 2011, responding to the pressure of events in neighboring North African states, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika lifted the state of emergency in effect throughout the country. Only Algiers remains in a state of exception, meaning that forming associations or participating in marches and demonstrations continue to be prohibited absent official authorizations rarely granted. A recent comic strip by noted cartoonist Slim depicts a citizen of the capital arrested by a gendarme for “marching” on the street and charged with the infraction of buying bread without a permit [Slim cartoon]. Gendarmes and police are perceived as the visible face of a corrupt and repressive regime.

[“Saturday” (Excerpt from Slim’s weekly comic strip, Le Soir d’Algérie, February 24, 2011]

Two policemen: Hey you over there, in the name of the law, I’m arresting you

Man: Me? Why?

Police: I saw you walking. You know that it is forbidden to walk on Saturdays.

Man: But I was going to buy bread!

Police: I don’t want to know that, the law is the law. Give me your permit to go buy bread and jump to it.

In contrast, the current Algerian standing army (officially the “People’s National Army”) of 350,000 soldiers once possessed a glorious revolutionary, anti-colonial history as the armed wing of Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN) that fought for and won Algeria’s independence from France by 1962. To this day, all Algerian male citizens must complete military service (now eighteen months versus Egypt’s three years’ conscription), which allows the armed forces to claim millions more as potential or active reservists. The formation of the post-independence army as of 1962 had drawn on the 50,000-strong “Army of the Border,” split between Morocco and Tunisia during the war of independence. It was headed by Houari Boumediene, who willingly incorporated Algerian career officers formerly from the French Army. Algerians under French colonial rule had been conscripted into the French Army, serving heroically in World War I, II, and Indochina as French subjects without the rights of citizens. During the Algerian war of independence, French conscripts were sent to Algeria, while Algerians, those conscripted by France or unable to desert, would be sent to do their required military service outside Algeria.

Following Boumedienne’s death in 1979 and until the recent past, that same generation of sclerotic generals and officers have been the actual rulers of Algeria. Many belonged to the “Lacoste promotion,” a class of men who earned officer rank in the 1950s under Robert Lacoste, resident minister of French Algeria. Certainly, one indication of a major shift by the 1980s in the ways in which the population viewed the Algerian army was the insulting name given to this cohort of generals based on their prior, shifting allegiances: “daf” from a French acronym, “deserters from the army of France.”

An analysis of the Algerian army’s organization reveals a mix of administrative and logistical elements. Historically, the army is not based on the administrative divisions of Algeria but retains the pre-independence, clandestine-era division into six regions. While its officer corps is French-formed, weaponry was Soviet, then Russian and Chinese purchases that reflected Algeria’s alignments with the Soviet bloc countries during the Cold War. Unlike the Egyptian army, the Algerian army has never created a self-supporting, autonomous (or perhaps parallel) economic sector in which the Egyptian army owns and profits from its own hotels, malls, real estate developments, farms, and more. Given Algeria’s hydrocarbon wealth, it doesn’t have to be entrepreneurial. Algeria’s military factories produce only materiel and equipment directly related to the business of soldiering, often through local licensing agreements with arms manufacturers from countries such as Russia and China. Nonetheless, decades of formal and de facto military rule have resulted in a military establishment that directs the country’s resources with the result that many individual, high-ranking officers have amassed great wealth. Despite internal military struggles during the 1990s black decade of Algeria’s civil war, their murky ties to Algeria’s vast hydrocarbon sector, and little knowledge about individual identities, it is the case that the Algerian military and its leaders remain a shadowy force -- outside any civilian framework and unaccountable to any institution but itself.