On February 24th the Algerian government lifted the state of emergency that has been operative in Algeria for almost two decades. Undoubtedly, this was a response to the changing political tides in the Middle East, as well as popular unrest in Algeria itself. While localized riots have been a common occurrence in the country since 2005, the start of 2011 has witnessed a wave of simultaneous protests in Algeria. On January 8th, the regime announced it would temporarily cuts taxes on sugar and cooking oil in an attempt to quell the protests. But that was before the Jasmine Revolution. After watching events in Tunisia, and then Egypt, Algerians were emboldened, taking to the streets even as the president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, refused permission for the protests and made sure that water cannons and police helicopters were readily available.

The 71 year old Bouteflika, who is widely believed to be in remission from cancer, has responded by lifting the state of emergency that had curbed freedom of expression and had been justified by the specter of political Islamism in the 1990s. This threat crystalized around the 1991 elections, in which the FIS emerged victorious and the military responded by annulling the results, dissolving parliament, banning the FIS and brutally cracking down on all stripes of Islamists. By most accounts, Bouteflika’s decision to end the state of emergency represents a minor victory in the wake of the confrontation between Islamic radicalism and authoritarian governance.

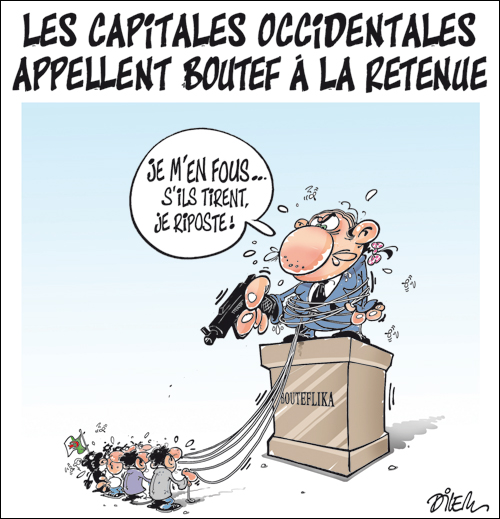

Yet in a recent editorial, journalist Azzeddine Bensouiah wrote that “the lifting of the state of emergency signifies absolutely nothing, in terms of action, for most Algerians.” Perhaps this is not surprising, given that Interior Minister Dahou Ould Kabila announced that marches would continue to be banned in the capital. And yet protests are set to continue. A different, but equally cynical, take on the uprisings was captured in a cartoon that ran in Liberté, and which depicted Bouteflika standing above a crowd, bound by ropes holding a gun at protesters trying to pull him down. Under the heading “international community asks Bouteflika for restraint,” Bouteflika remarks: “I don’t give a damn! If they pull, I’ll shoot.”

[Caroon by Dilem on 17 February 2011. Image from liberte-algerie.com]

While much has been written on the bloody war between the state and political Islamists, the role of foreign capital is much more opaque. The Islamists have received much press in recent weeks (no matter that there are important differences among these groups), but another kind of emergency has gone practically unmentioned: the 2001 Emergency Reconstruction Plan, which enacted economic reforms overseen by the IMF and stimulated significant foreign investment in Algeria (most of which occurred in the hydrocarbon industry). This “emergency” has been largely forgotten, but it goes a long way in explaining the recent cartoon as well as the political trajectory of Algeria in the last decade.

The act was certainly not Algeria’s first foray into the annals of the Washington Consensus. During the 1990s Algeria became dependent on foreign loans and adopted austerity measures that worsened unemployment. As a result, there was violent backlash by Algeria’s main labor union, the UGTA (General Union of Algerian Workers), which staged numerous strikes and protests. This was largely in response to the dual economy that had emerged between the oil and gas companies, on one hand, and the Algerian population, on the other. As one historian of Algeria has written, the government helped foster the “creation of veritable dual economies, with the oil and gas companies being physically shielded and isolated from the hostilities, while the general population went largely unprotected by security forces.”

Yet the attempt to attract foreign capital amidst a bloody civil war, which was spurred on by the polarizing logic of the first Gulf war and socio-economic unrest, posed considerable challenges. In an attempt to gloss over the deep political cleavages, some of which dated back to the war of independence, Bouteflika enacted a legalized form of political forgetting: the 2005 Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation

On a model that departed from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee, Bouteflika provided amnesty to members of FIS who committed acts of terror as well as agents of the state – which included the military and state officials. Officially, it stated that “Anyone who, by speech, writing, or any other act, uses or exploits the wounds of the National Treaty to harm the instructions of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, to weaken the state, or to undermine the good relation of its agents who honorably served it, or to tarnish the image of Algeria internationally, shall be punished by three to five years in prison and the fine of 250,000 to 500,000 dinars.” Three years later, in October 2008, Bouteflika asked for the suspension of the constitution’s article 77, which allowed him to stand for a third term. Once again, national security, political stability, and the specter of Islamism were used to justify the deepening of authoritarian rule.

And yet, to view authoritarianism and Islamism as a zero-sum game is to overlook the ways in which Algeria was imbricated in the global economy of oil and terror in the 1990s. The “dark decade,” which killed approximately 200,000 people was not simply a struggle between the state and the Islamists. Spurred by the concerns of foreign investors who were eager to see signs of political stability and the eradication of Islamism, the state had concrete incentives to radicalize the FIS rather than engage them in the democratic process. Moreover, FIS’ own internal divisions were deepened as the Salafists, trained in Afghanistan and hostile to any form of democratic participation, emerged on the scene. Eventually, these anti-democratic Islamists formed the GIA (Islamic Armed Group), which was initially funded by Osama Bin-Laden. The split between national Islamists groups committed to some form of political participation and transnational groups insisting on the destruction of the state has continued in Algeria, with the GIA eventually giving rise to the GSPC (Salafist Group for Call and Combat) and the AQMI (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb). In the early 1990s, while the regime was busy with FIS, more seditious enemies were emerging elsewhere, ironically funded by some of the same foreign interests that were investing in hydrocarbons. Foreign investment in Algeria has continued in the past decade - US direct investment in Algeria, for example, totaled $5.45 billion in 2007, most of which went to the hydrocarbon sector.

Both the Algerian state and radical Islamists were involved in transnational networks of terrorism and capitalism, which made the bitterest of enemies into occasional bedfellows. This peculiar combination of forces led to the mystery surrounding the murder of seven French Trappist Monks of Notre Dame de l’Atlas, who were kidnapped and killed in March of 1996. (It also happens to be the subject of the movie “Des Hommes et Des Dieux,” which recently won the award for best film at “French Oscars” last week.) While the GIA initially took responsibility for the killings, it later emerged that the GIA had undertaken the actions with the knowledge and potential complicity of the Algerian intelligence service (DIS). Thus, while the story of the showdown between the Algerian state and Islamists is not without validity, clearly the interests of the regime have been considerably more complex. As Algeria has emerged as a key ally on the “war on terror,” receiving financial and technical assistance in exchange for cooperation in matters of security, North Africa and the Sahel have become important locations for the security economy of the US, with Halliburton and their subsidiary, Kellog, Brown & Root, playing starring roles. Indeed, these events point to a recent history and political landscape that cannot be reduced to the corruption of local political elites, economic “mismanagement,” or the threat of radical Islam.

The divisive history of the war of Independence (1954 – 1962) as well as the violence of the 1990s continues to impact Algeria’s political landscape in important ways. The various groups that formed the National Coordination for Change and Democracy (CNCD) in January, which initiated the recent protests in Algeria, are undoubtedly diverse. They include the secular RCD (Movement for Democracy in Algeria), the communist MDS (Democratic and Social Movement), and the NGO, Algerian League for Human Rights (LADDH). Yet despite the 2005 attempts at reconciliation, and the lifting of emergency rule, things once forgotten are visible in the constitution of this group. For example, the fact that the participation of RCD, a mainly Kabyle party, has caused hostility, exposes the Berber unrest that continues to haunt Algerian national identity. Moreover, it is significant that the FIS’ recent request to join the coalition was denied, despite its considerable popular support. Lastly, while Hocine Ait Ahmed’s socialist party, the FFS (Socialist Forces Front) was initially involved in the coalition, it ultimately refused to join. Yet despite this fragmentation, the collective frustration is both palpable and undeniable. Indeed, the FFS responded to the lowering of prices in January with a statement that remains prescient for Algeria and beyond: “The government cannot buy Algerian’s silence.”

This article is now featured in Jadaliyya`s edited volume entitled Dawn of the Arab Uprisings: End of An Old Order? (Pluto Press, 2012). The volume documents the first six months of the Arab uprisings, explaining the backgrounds and trajectories of these popular movements. It also archives the range of responses that emanated from activists, scholars, and analysts as they sought to make sense of the rapidly unfolding events. Click here to access the full article by ordering your copy of Dawn of the Arab Uprisings from Amazon, or use the link below to purchase from the publisher.