When disturbed, they usually escape by running and rarely take to flight. (The Common Peacock)

In Rogues, his 2003 volume on rogue states,[1] Jacques Derrida looked to Plato`s Republic in order to assess the Grecian syntagma of democracy as ‘democracy to come.’ Passages from the Republic referring to ‘democratic man and his freedoms’ hold special relevance; Derrida used it to examine the rise of Islamism in Algeria but I would like to focus on the relationship between clothing, democracy and Egypt’s former president Hosni Mubarak and Libya’s embattled colonel-leader Mu’ammar al-Gaddafi. The Greek origin of aesthetics (aisthētikos) was largely indistinguishable from perception and perceptible things (aisthēta), and did not come to signify beauty or adornment until the relatively recent 18th century. A re-historicized rendering of the garments of despots might yield greater insight into the seduction and valor of democracy through its aesthetics or perception.

Democracy in this usage is modal, that is, it can contain different forms of regimes or states (panta genē politeiōn). The issue is not merely the choosing of which regime (or politeia) can constitute collective life, but that democracy appears as ‘all sorts of people, a greater variety than anywhere else.’ Most importantly, democracy appears. By no stretch of Platonic imagination does it appear as a fabric or tapestry that is most appealing when it is most vibrant and varicolored, as Derrida excerpts:

"Plato insists as much on the beauty as on the medley of colors. Democracy seems—and this is its appearing, if not its appearance and its simulacrum—the most beautiful (kallistē), the most seductive of constitutions (politeiōn). Its beauty resembles that of a multi- and brightly colored (poikilon) garment. The word poikilon, the key or master word in this passage, comes up more than once. It means in painting as well as in the weaving of garments—and this no doubt explains the allusion to women that soon follows—‘multicolored,’ ‘brightly colored,’ ‘speckled,’ ‘dappled.’ The same attribute defines at once the vivid colors and the diversity, a changing, variable, whimsical character, complicated, sometimes obscure, ambiguous. Because of the freedom and the multicoloredness of a democracy peopled by such a diversity of men, one would seek in vain a single constitution or politeia within it."

[Greek weavers. Image from metmuseum.org]

Of course, for all the insistence placed on sartorial metaphors for democracy, such as evincing women as the natural `weavers` of society (as much for their penchant for brightly-layered garments as for their gendered connection with textile arts), we know that the laborers of the cloth were not themselves allowed to partake in active civic duty.

"The making of textiles was one of women’s most important occupations in ancient Greece. A good weaver was considered an attractive woman and also a good wife. Homer describes Penelope, the devoted wife of Odysseus, busy at the loom day after day."

Weaving was afforded such eminence and women so metonymically connected to it that one could say involvement in garb and garments circumscribed actual involvement in the making of the republic. In other words, clothes literally made the civic man (and in a much more abstract way, the civic woman, who served as a draped ideal of plebeian democracy from ancient Greece to the Statue of Liberty).

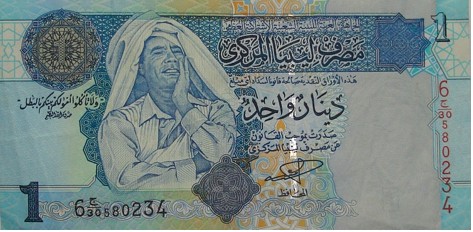

Undoubtedly many volumes could be written (it is less clear who would desire such a task) about Gaddafi`s public appearances, specifically the lengths to which he goes to distinguish himself as a unique and rare bird. Gaddafi adorns himself with accessories (an umbrella, another umbrella, a staff, another staff) as well as dizzying combinations and layers of loose, one-shoulder garments. They are extensions of his own superlative self-care—no living head of state would be emboldened enough to robe him/herself in such a way. Gaddafi not only embodies such daring accoutrements, but has also chosen to don his trademark aviator shades and draped head veils on official Libyan currency. His clothing and the national dinar—renamed from the Libyan pound in 1969,[2] when then-coup leader Gaddafi was still in ‘safari prints and sunglasses’—coalesce into one imaginary textile surface.

[Denominations of 50 and 1 Libyan Dinar. Images from Wiki Commons.]

The democratic ideal of the poikilon as a varied and brightly-colored garment alludes to two kinds of creatures: women, by virtue of their tendency to adornment, and proudly plumed peacocks. This resemblance may reinvigorate the logic behind (what I assume to be) a digitally manipulated photo of Gaddafi as poikílos, ‘spotted’ or ‘embroidered.’ The caricature is easy because Gaddafi is the subject of both fascination and horror in the way he transposes the appearance of sartorial freedom with the eradication of democratic freedom. Ridicule or amazement cannot obfuscate an underlying admiration for brazenness, which for Gaddafi translates freedom to dress as a metonymy for democracy.[3]

[Qaddafi as peacock. Image from www.russianblog.org]

Mubarak is in turns more demure in his sartorial choices, but that is irrelevant. I group him together with Gaddafi not to contrast the understatement of his clothing but to remark on the perception, that his pinstriped suit is perversely stitched with Mubarak`s own name, verifiable or not. (The telecasters refer to Reuters as the source of information about Mubarak`s suit, though I could not locate such a reference. This is largely unimportant: what matters is the perception of such an inscription, not to mention widely broadcasting it to the public at large.)

[Mubarak grimace. Image from bossip.com]

[Mubarak suit. Image from author`s screen grab of Youtube video.]

As one guest commentator in the video remarks, Mubarak’s suit screams, I AM EGYPT (ana masr). In a video posted by Ted Swedenburg as "yet another example of the great creativity and humor unleashed by the Egyptian Revolution," Mubarak’s clothing is cited in a protest chant as a metonymy of his oppressive rule.

"ehna meen ou huwwa meen / ehna el ‘amal wil fallah / ou huwwa harami linfitah Who are we and who is he? / We are the laborer and peasant / And he is the thief of the Infitah (Egypt`s ‘opening’—economic reforms, structural adjustment, etc.)

ehna meen ou huwwa meen / huwwa byelbes akher modah / ou ehna bneskon ‘ashara b’ouda Who are we and who is he / He wears the latest fashion / And we live 10 to a room"

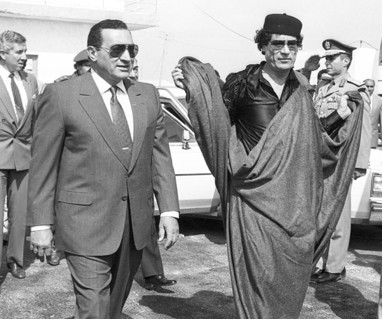

Photographer Frederic Neema remembers taking this iconic picture of Gaddafi and Mubarak 22 years ago in Marsa Matrouh, a frontier town that enjoins the Nile Delta and the Libyan border. Gaddafi arrived very late, Neema remembers, though one could inject, fashionably late:

"Gaddafi had finally crossed the border. Mubarak greeted him stiffly, visibly annoyed by the delay. They both walked towards the spot where both national anthems were to be played. It was at that moment that I took this picture. Gaddafi adjusted his robe in his usual royal fashion while starting to walk. I remember thinking how both men looked so powerful and untouchable at that time. [emphasis added]"

One could connect this photograph back to the Platonic notion of democracy as a modal, paradigmatic or constitutive framework, rather than the commonsensical understanding of ‘one man / one vote’ as we know it. Derrida: "If one wants to found a state, all one has to do is go to a democracy to pick out the paradigm of one’s choice. This market indeed resembles a bazaar (pantopōlion), a fair, a souk where one can find whatever one wants in the way of constitutions (politeia)." Whether staid suit-and-tie or robed drapery, the Mubarak-Gaddafi juxtaposition suggests power by self-styling, doing it our way, men cut from one cloth. While the Derridean textual reading is indispensable, we could fill in all the ways that a neoliberal political economy gets left out, that is, the leaders’ pan-Arabist pretensions and their actual collusions and secret agreements with those seen as betraying the Arab cause.

By way of conclusion, I return to Tunisia where the overthrow of former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali is thought to have hugely energized the current and ongoing uprisings in the region. The Ben Ali family wealth was found partially stashed in their armoires. At least one commenter referred to as "money in his drawers" (both in the sense of closet and underwear, sites of the pilfered ‘family jewels,’ so to speak).

[Ben Ali closet. Image from author`s screen grab of Youtube video.]

[Ben Ali watch. Image from author`s screen grab of Youtube video.]

As Derrida deduced in his Platonic reading of democracy, "the worst enemies of democratic freedom can present themselves as staunch democrats"—not least of all, one could add, through the veritable threads of their attire.

[1] Published originally in French as Voyous: Deux essays sur la raison. English translation by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas (2005). Derrida’s political tracing of rogue prefaces the book: ‘The word voyou has a history in the French language, and it is necessary to recall it. The notion of an Etat voyou first appears as the recent and ambiguous translation of what the American administration has been denouncing for a couple of decades now under the name of “rogue state,” that is, a state that respects neither its obligations as a state before the law of the world community nor the requirements of international law, a state that flouts the law and scoffs at the constitutional state or state of law [état de droit].’ All other citations refer to pp. 25-34.

[2] See prefatory notes in First, Ruth. Libya: The Elusive Revolution. 1974.

[3] For an eye-opening account of how ‘fashion came to matter as an emblem of democracy’ in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, see Pham, Minh-Ha, ‘The Right to Fashion in the Age of Terrorism,’ Signs, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Winter 2011), pp. 385-410.