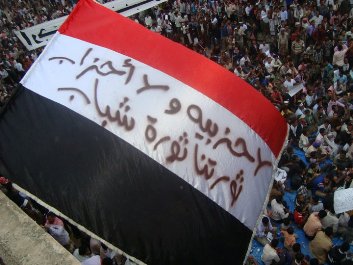

“Thanks, Tunisia! Congratulations Egypt! You are the trailblazers of freedom.”

The day after Tunisia’s leader fled his country on January 14, a group of Yemeni students at Sanaa University and members of Women Journalists Without Chains, led by Tawakul Karman, marched toward the Tunisian Embassy to show their support for the Arab world’s first popular uprising in 2011. In recent years, leaders of the Yemeni opposition coalition known as the Joint Meeting Parties (JMP) organized street protests in Sanaa and elsewhere around the country. As the wave of revolts spread from Tunisia to Egypt and other countries in the region, the JMP quickly announced plans for a massive nationwide rally.

On January 27, hundreds of thousands of protesters stepped onto the streets of Sanaa, Taiz, al-Hudayda, Aden, and other cities.

JMP rallies in Sanaa (above) and Taiz (below) were mainly expressions of progressive nationalist politics. In Taiz, many youth carried posters of Che Guevara. This signaled a resurfacing of Marxist politics, which has a long history in the country, especially in Aden and other cities of the pre-unity south.

Sign in right background above reads “Yes for Ending Oppression! (Arhal!) Leave!”

(Masdar Online; inset on lower right above is Tawakul Karman, director of Women Journalists Without Chains, who was arrested by al-mukhabarat police, and held for 30 hours on January 23-24).

During the preceding month, Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Salih (second from left in the following photo, widely circulated online using the label, “Rat Pack of Dictators”) pushed through a set of constitutional amendments ending any term limits on his role as head of state. Salih has long flaunted restrictions on his serving multiple terms, often rationalizing a “clean slate” for himself whenever the constitution is amended. In December 2010, the new amendments to the constitution eliminated all debate on the issue, paving the way for him to serve as president for life ... or so he thought.

The timing could not have been worse for Salih. Once Husni Mubarak appeared vulnerable in Egypt, Salih tried desperately to placate the demands of Yemenis crying “Irhal! Irhal!”

in the streets. At first, he promised to raise the salaries of public employees. Then he pledged not to run as president in the next election in 2013, and not to allow his sons to inherit his political power. But after pushing amendments to make him a life-long president, Salih could not possibly expect his countrymen to take seriously his pledge to step down after two years.

(Images from President Salih’s personal website)

President Salih’s standing in Yemen was badly undermined throughout the 2000s, due to economic crises inside the country, and also due to his alliance with President George W. Bush during the early years of the US “war on terrorism.” Note President Salih playing the role of Bush’s “right-hand man” in the above photos from a G-8 Summit Meeting in 2004 on Sea Island, Georgia. Salih appeared in traditional tribal clothing, including the curved dagger jambiyya, that he rarely wears at home.

Also note King Abdallah of Jordan on President Bush’s left side, as well as the only other Muslim leaders in traditional dress, Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan (standing behind Bush and King Abdullah), and King Hamad of Bahrain, standing two positions right of Karzai. Turkish Islamist prime minister Erdogan is behind Salih’s right side, more secure in his standing as a legitimately elected leader. Similar to Mubarak of Egypt, Bahrain’s Emir Hamad, and Muammar Gadhafi of Libya, Ali Abdallah Salih was more vulnerable to the 2011 popular uprisings because, during the previous decade, he cowered before American demands in the region.

When the street protests began in Yemen during the middle of January, Salih’s security forces initially used tear gas and stun grenades to disperse the opposition. JMP rallies on January 27 were allowed to proceed without disruption, but the regime made sure that the protestors in Sanaa did not occupy Tahrir Square as protestors in Cairo had been able to do. Later the regime unleashed its version of Egypt’s baltagiyya to attack the opposition in the streets. These thugs brandished sticks, stones, spears, and jambiyya, to assault young and old, male and female protestors.

Baltagiyya in Sanaa, Yemen. (Top, kiaoragaza.wordpress.com; bottom, Masdar Online)

In Sanaa, a few people died, and scores were injured in late January and early February. Similar clashes occurred in other northern cities, Taiz and al-Hudayda. But in southern cities, Aden, al-Hawta, Zinjibar, Mude`a, Lawdar, and al-Mukalla, the regime’s repression was far more severe. President Salih used heavy weaponry and armored vehicles against civilians. The contrast between the street scenes in north and south Yemen is similar to the contrast between scenes in Egypt and Libya. Grave war crimes have been committed in the south, where the number of people killed in the city of Aden is now more than two dozen, with hundreds injured.

There is no way to know how many protesters have been killed in other southern provinces because of very poor media coverage. Back in May 2009, the state shut down the main independent and opposition newspapers in south Yemen, following two years of popular rebellion against President Salih. Best known was the closure of Yemen’s oldest press, al-Ayyam, which is based in Aden and owned by the Bashraheel family. In January 2010, state security forces stormed the Bashraheel home in Crater, arresting the publisher Hisham Bashraheel and two of his sons. This followed a months long struggle between state security forces and the publisher who drew support from citizens in Aden. One person was killed and many injured, when state forces fired heavy weaponry and RPGs on the Bashraheel home.

President Salih resorted to these measures because, beginning in late 2007, al-Ayyam provided intense coverage of the main southern opposition (harakat al-junub). What triggered the Southern Movement was the killing of four young men in Radfan, one hour northeast of Aden, on the eve of anniversary celebrations commemorating the start of south Yemen’s revolution against British colonial rule back in 1963. The four men were shot and killed at the same location where British soldiers shot and killed seven Radfani men forty-four years earlier on October 14. Hundreds of thousands of citizens poured into Radfan to attend the young men’s funeral. Traffic was so heavy that the main road became clogged with cars, trucks, and buses (photos below). The masses walked the last several miles through rolling hills.

(Al-Ayyam, Hisham Bashraheel, 2007 Southern Movement)

For six consecutive months in late 2007 and early 2008, young and old attended daily sit-ins and rallies in southern towns and cities, where they pressed their demands for “equal citizenship” with northerners. Many southerners complained of living under northern military occupation, since a civil war in 1994 just four years after the country’s troubled unification. President Salih’s regime responded brutally to the Southern Movement, beating and arresting its supporters, before launching all-out warfare in April 2008. This radicalized the movement, and activists began demanding secession from the north. This led to even greater state repression in 2009 and 2010, when al-Ayyam and other papers were closed.

When the current uprising against President Salih started in January 2011, the regime did not hesitate to use brutal force against demonstrators in southern cities. Neighborhoods of Aden became clouded with thick smoke from buildings set alight by the firepower of the state, and from burning tires placed in streets by young protesters. The main districts of Crater, Tawahi, and al-Ma`ala, and the poorer, crowded outlying towns, Shaykh Othman and al-Mansura, became battle zones (below). Even wealthy inner-city neighborhoods like Khormaksar witnessed street fighting.

During the last few weeks, there is no doubt that state repression has been far greater in Aden than in Taiz and Sanaa. Two days ago President Salih forced the resignation of four elected governors in southern provinces because they would not compel local police to fire on protestors. It is the national army and security forces that are responsible for the killing. Horrific photos from Aden are now posted online, along with frightening video that shows large numbers of killed and injured.

This news from south Yemen is not penetrating the Arab and American media. In the US, there is great concern about the collapse of Salih’s regime because of its potential impact on American pursuit of al-Qaeda groups inside the country, especially in southern provinces Abyan and Shabwa. During the last two weeks, American media has kept its focus on events in Libya, where the downfall of the Gadhafi regime is perceived favorably. Arab television networks like al-Jazeera, which gave wall-to-wall coverage to the downfall of Mubarak’s regime in Egypt, and are currently devoting air-time to events in Libya, are downplaying developments in Bahrain and Yemen. Al-Jazeera’s reporters are also prevented from covering events in south Yemen, due to obstruction by President Salih’s regime.

(Images from Adenpress.com)

In the first cartoon above, Salih is depicted as a Rambo figure, carrying his last two southern prime ministers in baby pouches. Since the 1994 civil war, Salih has typically appointed southern officials to serve as prime minister, in order to create the appearance that he shares power in government. The cartoon signs surrounding Salih point to the six old provinces of the South Yemen.

In the second cartoon, the unification of Yemen is depicted as a ladder of opportunity for the elite few who hold positions of influence inside the regime. As the land of unity is sinking beneath rising waters, the elite man carries away his sack of booty, including state revenues, land property, top posts in government, and finally, the last fruits of the soil, the seas, and the air. South Yemenis regularly complain that their resources are stripped away for the benefit of northerners in Sanaa.

When protestors marched through the burning streets of Aden (below) in the face of fierce state repression, some young men carried the old flag of South Yemen with its red star inside a light blue triangle. This expressed the common view of people in southern provinces that their interests are best served by regaining independence from the north.

Meanwhile, in northern cities, below (the sign in the lap of young man in a wheel chair reads: “Peacefully! Peacefully! Oh, Leader of the Baltagiyya!”) nearly all protesters carried the standard Yemeni banner.

A carnival atmosphere prevails in peaceful northern rallies, where families can attend street protests with young children who often have their faces painted with patriotic themes.

The change that is coming to Yemen will require all citizens to address painful divisions still lingering in the country, if Yemen’s national unification is to be preserved. When north and south united more than two decades ago, politicians and citizens were in denial about the multiple divisions splitting Yemeni society, many of which arose from earlier conflicts that engendered strong feelings of vengeance. Acts of political violence and assassination quickly shattered the illusions of unity, and continued for years after Yemen’s 1994 civil war. The current leadership is heavily implicated in this violence, as are members of the political opposition.

The former regime of South Yemen was notorious for its political infighting. Intra-regime warfare erupted in Aden in January 1986, leading to thousands of deaths. Cuban leader Fidel Castro, an ally of the former Marxist leaders of South Yemen, once posed a question to members of the Socialist Party: “why on earth do you like killing each other so much?” Now in 2011, at a time of hopeful change, all Yemenis need to ask the same question, and look inward, before they can forge a future different from the past. Real change requires mending national unity, and striving to overcome regional, tribal, and religious prejudices that caused such destructive conflicts in the past.

Establishing an open democracy, one that represents the public welfare and the best interests of the nation, will be key. Western-style parliamentary democracy, with its partisan politics and hotly contested winner-take-all elections, may not be the best approach. United Yemen went down this road between 1990 and 1993, and it resulted in civil war. The path forward in Yemen, blazing a new trail of genuine freedom and equality, requires ending the current regime and its ruling party, the General People’s Congress (GPC). The GPC is now calling the opposition to dialogue and negotiation. But GPC leaders have made a mockery of the word “dialogue.”

(Masdar Online. Student protestors in Taiz are fed up with politics of the old parties in Yemen, so on this Yemeni flag they wrote: “No partisanship! And no parties! Our revolution is a revolution of youth”)

Over the decades, the GPC became a corrupting influence in Yemen, behaving like other one-party ruling systems. In the 1980s, the GPC even adopted a partisan booklet, much like Gadhafi’s “Little Green Book,” which was required reading for all public employees. On the last day of each work week, they sat in their offices, or in classrooms, absorbing an ideology that primarily served the interests of Salih, his family and tribe. The population has no patience for GPC leaders who seek a negotiated end to the current crisis.

.jpg)

(Masdar Online. Protesters in Sanaa hold a sign that reads “No negotiation! No dialogue! Only two choices: Resignation or Exile.”)

The path forward in Yemen also requires changing the military culture of the country. In the photo above,a soldier in Sanaa, named Adam Ahmed Amin al-Hameeri, resigned from the army on February 21. Al-Hameeri declared his support for the street protests because of “the neglect that soldiers suffer in the security and armed forces, where they are used as spearheads in wars that only benefit the state’s leadership.” He referred specifically to the recent war in Sa`da province and other areas north of Sanaa, where thousands of soldiers died or were injured in battles against fellow countrymen. “I, as a simple soldier in the army, declare my stand in solidarity with the protests that are demanding the fall of this corrupt regime, which steals Yemen’s valuable resources. And I want to inform you that all of the soldiers in the armed forces are standing with you, even though they may wear the army’s uniforms.”

Yemen’s armed forces need to be reformed along national lines, eliminating recruitment and promotions based upon tribal and regional criteria. Past methods of recruitment and promotion fed divisions in the country, fomenting internal conflicts and civil war. Yemen’s military and security forces can no longer be used against citizens of the country, women and children, as they have in the last several years. All institutions of the state, military and civilian, must be converted for use in service of the interests of all Yemenis. Once the old regime is removed, the new government’s focus should be twofold: creating social peace, and providing public welfare. The younger generation should be called to step forward, forming a national service corps. A higher percentage of state revenues should be set aside for job creation and economic development. Yemeni women have an important role to play, and they should be encouraged to serve on equal terms with men. Women are capable of serving as leaders, as indicated by the inspiring role that Tawakul Karman played in the early street protests.

.jpg)

(Yemen Times. Tawakul Karman with her three daughters.)