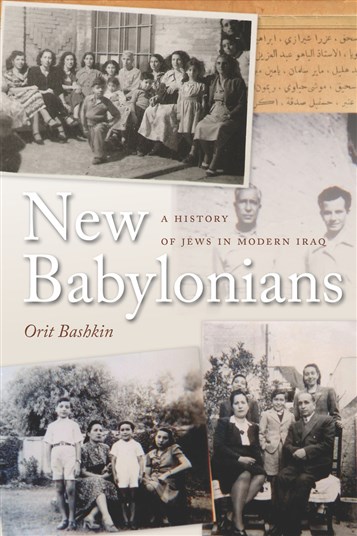

Orit Bashkin, New Babylonians: A History of Jews in Modern Iraq (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2012).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Orit Bashkin (OB): I became interested in the topic as a teenager, reading Hebrew novels written by Iraqi Jews who described their experiences in Iraq. When I was working on my first book I met Iraqi Jews who spoke to me about their experiences in Iraq, and Iraqi Muslims and Christians who spoke about their Jewish friends and neighbors. What amazed me about some of these conversations was the personal memories of Iraqi Jews now living in Israel; their Iraqi-patriotic sentiments and their longing for Iraq did not simply disappear when these individuals migrated to Israel. They were also passed on to their children and grandchildren, even if in a partial and incomplete fashion. I saw how, regardless of their political status as Israeli citizens, the memories of their Arab pasts shaped their present; I therefore wanted to understand the Iraqi context that enabled this Arab-Jewishness to exist and to flourish.

Moreover, these taboo memories, as Ella Shohat calls them, have important political functions. They remind us that the national divisions we accept today were not always normative and commonsensical. In Israel, the generation of Jews who lived in Iraq and absorbed its Arab culture is slowly disappearing, and the commitment to preserving such memories seemed crucial to me. I hope I was successful.

The book, as I see it, is part of the attempts of scholars to write a post-Orientalist history of Arab-Jewish communities.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address

OB: The book, as I see it, is part of the attempts of scholars to write a post-Orientalist history of Arab-Jewish communities. It delineates the ways in which Iraqi Jews took up Arab nationalism and Iraqi patriotism. The notion of Islam as a civilization rather than a religion, advanced by many Muslim modernists and Arab nationalists, appealed to Iraqi Jews, and they thus looked at the heroes of these Arabo-Islamic cultures (ranging from poets like al-Ma‘arri to philosophers like al-Farabi to modern poets such as al-Sayyab) as their own. Reading about these visions of the Iraqi nation, I was reminded of the fact that in 1940s, Michel ‘Aflaq advised fellow Arab nationalists to consider Muhammad an Arab prophet whose Islamic culture was relevant to all Arabs. Although by no means a fan of the Ba‘th (to use the understatement of the century!), I felt it is worth noting that Iraqi Jewish intellectuals were proponents of such ideas long before they became pillars of Ba‘thi ideology.

Writing on Arab-Jewish history, I also tried not to engage with the binary Arab-Jew/Zionist but rather to consider a variety of expressions of Arab-Jewishness in Iraq. Thus, I analyzed the urban experiences of the educated Iraqi Jewish middle classes and their perceptions of secularization, reform and gender relations, the Arabic literary production of Iraqi Jewish journalists, novelists, short-story writers and poets, and the radical visions of Arab-Jewish communists, especially the communist Jewish league ‘Usbat Mukafat al-Sayhuniyya (The League for Combating Zionism). I also showed how these visions of Jewish Iraqi patriotism and nationalism were shattered following the 1948 War in Palestine, when Iraqi Jews—their lives, their property, and their places of dwelling—became mere pawns in the Arab Israel conflict.

J: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research and writing?

OB: My first book The Other Iraq dealt with Iraqi intellectual history. I tried to look at democratic, radical, and secular visions of Iraqi society as expressed in the Iraqi public sphere of the monarchic era (1921-1958). Also, following insights from scholars like Ussama Makdisi and Max Weiss, who look at sectarianism as a modern phenomenon, constructed by the state and the colonial powers, I tried to unpack the problematic notions affiliated with sectarianism and to understand their modern and colonial constructions. My new work is, in many ways, a continuation of the first project. Jews were an active part of the Iraqi public sphere. They played a major role in the shaping of interwar Iraqi culture, and were excited about the new literary and cultural developments in interwar Baghdad. With respect to sectarianism, I attempt to show how Jews advocated various political solutions to cope with the several sectarian mechanisms created by the state, Britain, and different groups within Iraqi society.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

OB: Given the effort to erase the memory of Arab-Jewish experiences in Iraq by the Ba‘thi state, I want Iraqis who read this book to know about the Jews who lived in Iraq and considered Iraq as their homeland and Arabic as their mother-tongue. In some sense, I want to commemorate an Iraqi social context in which Jews and Muslims were business partners, neighbors, and friends. Naively, perhaps, I also want to believe that understanding the Iraqi Jewish past could inform our thinking about the situation between Israelis and Palestinians, and between Jews and Arabs more generally. The introduction of Israeli Jews to Arab history and the Arabic language could serve as a useful way to counter present-day myths about the eternal, mutual hatred of Jews and Muslims. I have very little hope that the Israeli state would do anything to change this situation, but I do hope that groups within Israel—students, intellectuals, Mizrahi Jews, interfaith groups, and so on—will try to teach themselves, and their children, Arabic, Arab history, and Arab-Jewish history, in a way that is not dependent on the state.

Finally, I feel that the book might serve as an antidote to Islamphobic notions existing in Western countries. Many of us encounter printed and online publications detailing the mutual hatred of Arabs and Jews and “Muslim anti-Semitism.” Those are often produced by a wide range of organizations that prefer to speak about a Judeo-Christian tradition rather than a Judeo-Islamic one. I wish to remind these readers about visions of tolerance, pluralism, and democracy that came into being in a modern Islamic context. We should be talking more about Judeo-Islamic cultures, and I hope this book will play a part in this process.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

OB: One of the projects I am working on has to do with nineteenth-century historical novels in Arabic and, more broadly, with the representations of Jews in the works of the luminaries of the Arab literary and cultural revival of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. As recent scholarship has shown, leading Arabic journals from this period protested the persecution of Jews in Europe; reported about pogroms and anti-Jewish activities, especially in Russia and the Balkans; and noted favorably that Jews were granted certain citizenship rights in Britain and Germany. These Arab intellectuals did so, in part, in order to expose European doublespeak, as Arab intellectuals underlined the fact that Europe, seeking to represent itself as the beacon of justice, democracy, and modernity, was treating its own minorities in an appalling fashion. Engaging in these discourses was also a way to promote non-religious understandings of citizenship. Novels, historical novels in particular, conveyed these notions.

A recent work of mine explores the historical Urshalim al-Jadida (“The New Jerusalem”) written by the Christian intellectual Farah Antun (1874-1922). Chronicling a love affair between a Jewish woman, Esther, and a Christian man, Iliya, during the Arab conquest of Jerusalem (in the year 637), the novel promoted new ideas of Ottoman brotherhood and secular citizenship rights. I examine this novel also in connection to Antun’s condemnation of French politicians for their colonialism and their anti-Semitism as exposed in the Dreyfus affair, and his admiration of Emile Zola.

J: What methodologies did you use in your research toward this book?

OB: I think the book engages with theories related to nationalism, which have tended to emphasize the modern and constructed nature of the national project. I also see this work as part of the efforts of postcolonial writers to underline the impossibility of imagining a stable orient and occident in a globalizing and capitalist world. I therefore underline the constant dialogues between various cultural centers in Iraq, the Middle East, Europe, and America and illustrate how such dialogues created a unique Jewish Iraqi experience, which was nonetheless intertwined with global and Western discourses.

To conclude with something that is more of an anecdote: When I was doing archival work in Israel, I visited the Arab neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem. On the one hand, the demonstrations that occur in Sheikh Jarrah on a weekly basis were very hopeful, as Arabs and Jews combine their efforts to protest the denial of human rights to Palestinians in Jerusalem. On the other hand, the anti-Palestinian settlement policies in the neighborhood represented, to my mind, the exact opposite of the Jewish–Iraqi coexistence in the mixed neighborhood of Baghdad that I have described in my book. Perhaps the Iraqi Jewish story could elucidate that contemporary Sheikh Jarrah is the abnormality, while interwar Baghdad should be the norm.

Excerpt from New Babylonians: A History of Jews in Modern Iraq

The Question of Palestine: The League for Combating Zionism

In September 1945, eight Jewish communists requested a license from the Iraqi Ministry of Interior to form a political organization, the expressed aim of which was to oppose Zionism. They were: Salim Menashe, who worked with the shoemakers union; Ibrahim Naji Shumail; Ya‘qub Ephraim Sehayek; Nisim Hesqel Yehuda, a proprietor; Moshe Ya‘qub, the president of the tailor workers’ union; Ya‘qub Cohen, a clerk in al-Fattah’s cloth factory; Masur Qattan, an editor of the newspaper Al-Sha‘b; and Ya‘qub Masri. The license was eventually granted, paving the way for the League for Combating Zionism, as the organization was called. This organization came to be very influential in both communist and the Jewish circles, and in 1946 managed to draw the attention of a wide range of actors in Iraq—Iraqis, Jews, and the British alike.

The league’s conceptualizations focused on three domains: Jewish, Iraqi, and Arab. In the Jewish domain the league attempted to present its criticism of Zionism from a Jewish vantage point, maintaining that the Jewish religion could not form the basis for a national community and that the solution to the Jewish problem should be sought within the communities in which Jews lived. In the Iraqi domain, the league argued that Iraqis who equated Judaism with Zionism were fomenting sectarianism and suggested that the struggle against colonialism within Iraq, as well as the domestic campaign for democratic freedoms and social justice, should be viewed as part of a comprehensive battle for liberation, of which the struggle against Zionism was one aspect. On an Arab Palestinian level, the league called for the creation of a free and democratic Palestinian state. The league’s pamphlets and publications deployed the term “Arab Jew” to mark the identity of its members, thus giving us an idea as to the meanings ascribed to this term in the communist context. As many members of the league were Jews themselves (although its ideas were favorably received by Muslims and Christians), its activities illuminate the ways in which Jewish communists imagined their Arab community.

The secretary of the league and the editor of its journal was Yusuf Harun Zilkha, a former member of a communist splinter group called Wahdat al-nidal, who returned to the ICP in 1941. His day job was a clerk in the rail authority. The league’s ideas were most lucidly outlined in his book Zionism: The Enemy of the Arabs and the Jews, which endeavored to provide a historical narrative for the Jewish problem that attended to Arab, Iraqi, and Jewish concerns. Zilkha argued that the Jewish problem was not abstract, but rather ought to be contextualized within specific periods and socioeconomic conditions. In his opinion, the existence of Jews as a minority within non-Jewish societies had a very long history, going back to Assyrians’ exile of the people of Israel from their land. This trend had solidified under the Babylonians, when the people of Judah became one of the ancient communities of the Near East. Notably, even when given permission to return to Palestine in antiquity, not all Jews had chosen to leave Babylon and resettle in their place of origin. Jews had continued living in exile from that moment on, being affected by, and affecting, each community in which they lived.

Zilkha believed that the Jewish problem was related to the class struggle. Whenever the ruling classes felt threatened by a new class, they used the Jews as a convenient scapegoat in order to distract the masses from their real problems. This global practice was particularly noticeable when either a state or a ruling class was on the verge of collapse. In the modern age, the Jewish problem had become more acute. The French Revolution had sown the seeds of liberty in modern Europe, causing the reactionary movements which emerged after the Napoleonic wars to unleash a racist campaign against European Jews as part of a more general attempt to curtail the democratic rights of the subjects of European empires. As the class struggle intensified, Jews suffered increasingly from racist and anti-Semitic campaigns. Continuing into the twentieth century, the most obvious manifestation of this phenomenon was the Nazi regime. Capitalist Germans, facing threats from the workers, turned against Jews who were blamed for all the ills of capitalism, in particular unemployment and the global economic crisis. Germany and Italy, however, were not the only places where the toxic mixture of anti-Semitism and capitalism took root. In Britain, fascist groups, such as that of Oswald Mosley, adopted similar ideologies. Dangerously, pro-Nazi movements had spread in the colonies and in semicolonized countries, such as Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. Even with the defeat of Nazi Germany and the Axis, anti-Semitism did not disappear. Presently, wrote Zilkha, anti-Semitic propaganda focused on breaking down the unity of national liberation movements in the colonized world and separating the ranks of the working classes.

Zilkha’s analysis, however, provoked the following question: if anti-Semitism and racism were so dominant in European culture and history, why not turn to Zionism and seek a solution in Palestine, where the Jews could have a sovereign state of their own? In response, Zilkha argued that when Jews joined a shared struggle with the working classes in the countries in which they lived, their conditions improved and anti-Semitism declined. Jews and non-Jews should therefore fight together against anti-Semitism and strive for the attainment of democratic freedoms.More importantly, Zionism in itself could only lead to an increase in anti-Semitism.

Zilkha’s critique of Zionism included a few components. To begin with, he contended that religion alone could not serve as a basis for a national community. He defined a nation as a group of people who share a common history, language, territory, economic life, and collective mentality. From this perspective, Jews could not be considered a nation:

Jews do not have a shared history. The history of Arab-Jews [al-yahud al-‘arab]…is different than the history of Russian or British Jews. The history of German Jews is different from the history of Turkish or American Jews and so on. For example, British Jews are part of the British nation [umma], just as the Arab Jews are part of the Arab nation. The Jews do not have a common territory. They do not have a shared language, because German Jews speak German, British Jews speak English and Arab Jews speak Arabic….They do not have a shared mentality [takwin nafsi] that manifests itself in a shared culture, because they lived for thousands of years in various communities, and became part of the societies in which they lived.

Zionism, moreover, was an antidemocratic movement, since it did not seek to give equal freedoms to all the inhabitants of Palestine, privileging only one group, the Jews, over the Palestinian Arabs. From its very inception, the movement’s leader, Theodor Herzl, had sought the help of authoritarian rulers, such the Ottoman sultan ‘Abdulhamid II and the German kaiser, to support its exclusionist agenda. Although labor Zionism claimed to be socialist, whoever considered himself a socialist could not but object to a regime that preferred one ethnicity over the other in the labor market. The Histadrut, supposedly a labor union, was in fact an organization which employed workers in the same companies it controlled and only respected the rights of Jewish workers. Consequently, Palestinians suffered from high unemployment because of the unfair competition between Arabs and Jews in the market.

[Excerpted from Orit Bashkin, New Babylonians: A History of Jews in Modern Iraq, by permission of the author. © 2012 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. For more information, or to order the book, click here.]