Lisa Hajjar, Torture: A Sociology of Violence and Human Rights. New York: Routledge, 2012 [“Framing Twenty-First Century Social Issues” series].

Jadaliyya (J): What inspired you to write this book?

Lisa Hajjar (LH): Torture is my great and terrible obsession. I think, read, write, and talk about torture all the time, as anyone who knows me can attest. I was inspired to write this book in order to share my knowledge, my passion, and—to be blunt—my anger about torture with college students, although hopefully people who are not students also will find it interesting. This book, like others in the Routledge series, Framing Twenty-First Century Social Issues, is geared primarily to college classroom teaching; it costs less than ten dollars, is about sixty pages long, has discussion questions at the end of each chapter, and a glossary of key terms and concepts at the back.

Of course everyone who writes books hopes lots of people will read them. But my inspiration for writing this book is partly instrumental: I hope that many students will be assigned Torture in a class, and that reading it will inspire them to contribute to changing the national conversation about torture. The national conversation in the US continues to be dominated by those who propagate falsehoods, like the ludicrous assertion that torture produces “good intelligence,” or that waterboarding is not “torture” if Americans do it, or that some people have no right not to be tortured. I wrote this book in order to arm students with information and analysis so that they might be intellectually empowered to be boldly, aggressively, and unapologetically anti-torture. This book is a cri de couer to the next generation of leaders and voters.

Another inspiration for writing this book was a desire to synthesize my work on law and conflict, violence and human rights in one slim and accessible volume. I boiled down and blended some of the arguments that are dispersed in various scholarly articles and chapters. Among the key questions that I raise and answer in this book are: Why do states torture? Does torture work? Why is the right not to be tortured so uniquely important? Why is torture so prevalent? Why is accountability for torture so important legally and so fraught politically?

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

LH: This book is not just about US torture in the “war on terror,” although that is how it begins and ends. It includes a history of torture, going back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. The use of violence to elicit statements from suspects or witnesses to crimes in these ancient law-state-society complexes made the practice of torture necessary and legitimate means of enforcing the law and maintaining social order. Starting in the twelfth century, the reliance on torture to obtain confessions was replicated and expanded in continental Europe. The practice of pre-modern torture was affected by major historical events, like the Black Plague, the Protestant Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, and centuries of religious wars, inquisitions, and witch hunting.

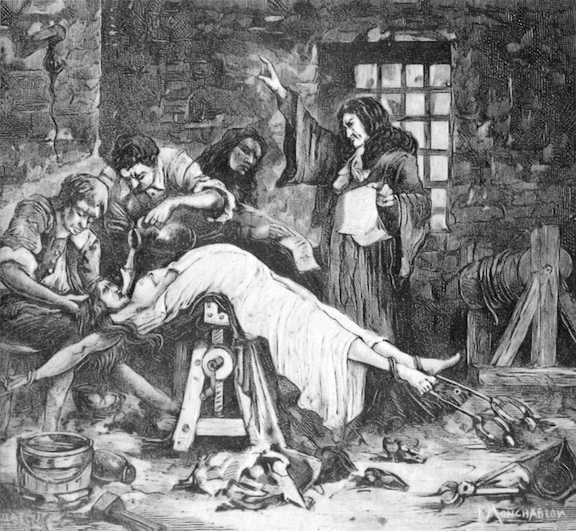

[The Marquise de Brinvilliers being tortured with water before her beheading, by F. Monchablon. Image from Wiki Commons.]

The history of torture is also deeply embedded in the socio-political and legal transformations that mark the rise of modernity. Starting in the eighteenth century, torture was abolished from the legal systems in many countries in the sense that it was no longer an acceptable means of law enforcement to elicit confessions. The abolition of torture and its political delegitimization are integral to the emergence of the modern rule of law and limitations on governmental powers, political transformations of state sovereignty to reflect and accommodate demands for national self-determination, and the socio-legal construction of human beings as rights-bearing subjects. The first extract below is drawn from the section of the book that discusses abolition and delegitimization.

Yet despite abolition and delegitimization, torture did not stop. Rather, it went “underground,” so to speak, to become an extra-legal practice, usually conducted in clandestine or otherwise inaccessible settings. The paradox of torture in the modern era is that it is both pervasive and illegal. I explain its twentieth and twenty-first century pervasiveness by anchoring the analysis around two key questions: Why torture? Who is deemed torturable? In answering these questions, I offer a comparative framework that highlights the relationship between regime types (totalitarian, authoritarian, colonial, democratic) and official perceptions and practices of national security. I provide examples drawn from all over the world. The second excerpt below discusses Israeli torture of Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza.

The other side of the paradox, torture’s illegality, opens up a vista onto the relationship among violence, rights, and law. The legal abolition of torture produced the right not to be tortured; this is a negative right, meaning that there is no right to engage in the prohibited practices that are legally defined as torture. I use the discussion of torture and rights to engage more broadly and comparatively with different kinds of rights, including the creation and development of human rights in the post-World War II era. I also emphasize that torture is a crime, comparable in some ways to other gross crimes in international law: genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. In the post-Cold War era, the enforceability of international criminal law has undergone some substantial changes, including the establishment of new institutions and new uses for the doctrine of universal jurisdiction. I link these developments to recent efforts to hold people responsible for torture legally accountable.

In the last part of the book, I discuss the effects of torture on victims, perpetrators, perpetrating institutions, and whole societies where torture is or has been rampant. The third excerpt below locates the consequences of US torture in a broader global and historical perspective.

J: How does this work connect to your previous research and writing?

LH: The most enduring theme of my scholarship focuses on contestations over “what is legal” in the context of war and other forms of violent political conflict. My first book, Courting Conflict: The Israeli Military Court System in the West Bank and Gaza (University of California Press, 2005), includes extensive research on torture as a multifaceted phenomenon, as well as anti-torture activism and litigation. Since 9/11, much of my work has focused on the US global “war on terror,” especially the government’s interrogation and detention policies.

Because US policies in the post-9/11 era either resembled or emulated the Israeli government’s approach to law and conflict, my expertise on Israel/Palestine positioned me to be an early interlocutor and analyst of some of the most contentious issues arising in the context of the “war on terror.” Because the Bush administration strived to “legalize” torture through a radical reinterpretation of international and domestic laws governing the interrogation and detention of prisoners captured in war, litigation emerged as—and remains—the primary strategy for challenging American torture and other issues related to the status and treatment of such prisoners. Anti-torture work in the US has been dominated by lawyers, and cumulatively takes the form of a legal campaign. I am writing a monograph based on my ethnographic study of this anti-torture legal campaign.

[Israeli interrogators routinely used hooding, stress positions, and painful cuffing. Image by David Gerstein.]

I have deep respect and admiration for people who have engaged in the hard and often frustrating work of fighting against the use of torture and pursuing accountability for perpetrators. In the US, theirs has been a rather lonely struggle, in the sense that there has emerged no wider popular support for these causes. On the contrary, according to numerous public opinion polls and social scientific research, popular acceptance of torture is on the rise. By writing this short teaching book, I hope to contribute to changing that fact by raising students’ (and others’) awareness about what is wrong with torture.

Excerpts from Torture: A Sociology of Violence and Human Rights

In the late eighteenth century, European legal systems were reformed to eliminate judicial torture, and by 1800 almost no traces were left. The abolition of torture coincided with moves to disallow some punishments that involved public humiliation, protracted physical suffering, and bodily disfigurement (e.g. racking, drawing and quartering, burning at the stake, and mutilation). The guillotine was invented to be an efficient and painless form of execution.

Although Enlightenment thought and a new spirit of humanitarianism were factors in the abolition of torture (Hunt 2007), many scholars contend that a variety of changes in law–state–society complexes must be taken into account. Langbein (1978, 2006) emphasizes the importance of changes in criminal procedure, including reforms allowing people to be convicted for serious crimes on the basis of circumstantial evidence. Others emphasize the development of modern forms of imprisonment as alternatives to execution or excruciating pain (Foucault 1977).

The de-legitimization of torture is related to its legal abolition but derives more squarely from changing models of sovereign statehood (see Chapter 3). The American and French revolutions to establish democratic forms of government reconfigured relations between states and people, and the legal rights of each. The key architects of these revolutionary transformations advanced ideas that “all men” had “inalienable rights” and “dignity,” and that government powers should be limited by law. Torture was regarded as incompatible with democracy because it represented “tyranny in microcosm” (Luban 2005, p. 1,438).

In America, the de-legitimization of torture traces back to the founding of the republic. The Eighth Amendment to the US Constitution, passed in 1791, prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments.” Along with habeas corpus (the Great Writ which prohibits officials from imprisoning someone without a good and legal reason) and the separation of powers to provide checks and balances on the branches of government, the ban on unconstitutional cruel treatment served as a foundation of the modern rule of law because it was understood as essential for conditions of liberty, limited government, and due process to thrive. Also, judicial torture to interrogate suspects contradicted one of the nation’s founding legal principles: the presumption of innocence. However, court-ordered punishments of people found guilty, no matter how cruel the methods might seem, were lawful. Thus, the line-drawing between judicial and penal torture was complete: judicial torture was prohibited, and penal torture was folded into the law.

Colin Dayan (2007, p. 88) writes that the founding fathers selected the words “cruel and unusual” in the context of the decision to make slavery constitutional. In cases involving violence against slaves, judges often accepted that the condition of slavery necessitated certain cruelties, and only extreme and malicious abuse—for example depriving slaves of food or clothing—would rise to the level of a constitutional violation. After slavery was abolished at the end of the American Civil War, Dayan argues, legally permissible cruelties were transposed into the criminal justice system. Prisoners, like slaves, are “unfree.” In contemporary cases pertaining to the treatment of prisoners, judges have accepted that the conditions of imprisonment may necessitate cruelties and deprivations, but these would not be constitutional violations unless they involve malicious intent or failure to provide for “identifiable human need such as food, warmth, or exercise.” Thus, Dayan writes, the legacy of the slave era “still haunts our legal language and holds the prison system in thrall” (p. 16).

Echoes of this history of interpreting the law in such a way that certain classes of people have been deemed to have no right not to be subjected to violent and dehumanizing treatment can be heard in the legal reasoning in the “torture memos” (discussed in Chapter 1).

[…]

For two decades, allegations that interrogators working for Israel’s General Security Service (GSS) tortured Palestinian detainees for confessions and intelligence were consistently denied by government officials as lies and fabrications of “enemies of the state.” Then in 1987 (for reasons unconnected to the interrogation of Palestinians), the Israeli government established an official commission of inquiry to investigate the GSS. The Landau Commission confirmed that GSS agents had used violent interrogation methods on Palestinian detainees since at least 1971, contrary to official denials, and that those agents had routinely lied when confessions were challenged in court on the grounds that they had been coerced. The Landau Commission was harsh in its criticism of GSS perjury (i.e. lying to military judges), but adopted the GSS’s own position that coercive interrogation tactics were necessary in the struggle against “hostile terrorist activity.” The Landau Commission adopted a broad definition of terrorism to encompass not only acts or threats of violence, but all activities related to Palestinian nationalism.

The Landau Commission report concluded that the defense of Israeli national security requires physical and psychological coercion in the interrogation of Palestinians, and recommended that the state should sanction such tactics in order to alleviate the problem of perjury. The Landau Commission’s justification for this recommendation was based on a three-part contention: that Palestinians have forfeited their right not to be abusively interrogated because of their predisposition for terrorism, that the GSS operates morally and responsibly in discharging its duties to defend Israeli national security, and that GSS interrogation methods do not constitute “torture.” The Landau Commission sought to avoid the scourge of the torture label by euphemizing the endorsed tactics “moderate physical pressure.”

The Landau Commission’s reasoning that “moderate physical pressure” does not constitute “torture” traces back to British interrogation methods used on IRA prisoners. The Commission noted that Israeli interrogation tactics resembled the five techniques, and embraced the [European Court of Human Rights] majority decision that they do not rise to the level of torture. These tactics include stress positions, protracted sleep deprivation and isolation, prolonged hooding, sensory manipulation (e.g. excruciatingly loud noise), and painful cuffing.

In November 1987, the Israeli government accepted the Landau Commission’s recommendations and officially authorized “moderate physical pressure.” Thus Israel became the first state in the modern world to publicly endorse the use of painful, degrading, and inhumane interrogation techniques as a “legal right” of the state. The timing of this license to torture was unpropitious because in December 1987, Palestinians started an intifada (uprising) to protest the continuing occupation. This mass movement was, initially, unarmed. Israel responded with armed force as well as a massive increase in arrests, interrogations, and prosecutions through the military courts. At the end of the 1980s, Israel had the highest per capita prison population in the world.

In the early 1990s, Palestinian Islamists affiliated with Hamas and Islamic Jihad, which were political competitors with the more secular PLO, began using the tactic of suicide bombing, sometimes as reprisals for Israeli assassination operations. In response to the heightened insecurity caused by such bombings, Israeli interrogational torture increased. However, contrary to the hypothetical ticking bomb scenario (see Chapter 1), which the Landau Commission had invoked in arguing the necessity of abuse, there has never been a documented instance of an actual ticking bomb (i.e. one that is imminently set to explode) that was discovered and defused through torture. Rather, in Israeli national security discourse, Palestinian resistance to the occupation—both violent and non-violent—is the ticking bomb.

In response to the Israeli government’s authorization of tactics and treatment widely regarded as torture, some Israeli and Palestinian lawyers and human rights activists waged a decade-long battle in Israeli courts to end the use of “moderate physical pressure.” Those efforts ultimately were victorious when, in 1999, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled that the “routine” abuse of detainees was unacceptable and prohibited. Israeli interrogational abuse of prisoners did not stop completely (PCATI 2003), but that court decision deprived it of the veneer of legality.

Ironically, the Israeli model of “legalizing” torture as necessary in the fight against terrorism was influential for the authors of the US “torture memos” (see Chapter 1), but not the court decision that ruled against the routine and systematic use of abusive techniques.

[…]

The legacy of American torture confirms timeless truisms about the dubious relationship between pain and truth. “Torture,” as 3rd-century AD/CE Roman jurist Ulpian observed, “is a difficult and deceptive thing[,] for the strong will resist and the weak will say anything to end the pain.” As for truth, according to the German Jesuit Friedrich von Spee in 1631, “It is incredible what people say under the compulsion of torture, and how many lies they will tell about themselves and about others; in the end, whatever the torturers want to be true, is true.” For a contemporary judgment, Darius Rejali (2007, p. 478) explains the ineffectiveness and destructiveness of torture, which fits the US case: “[O]rganized torture yields poor information, sweeps up many innocents, degrades organizational capabilities, and destroys interrogators. Limited time during battle or emergency intensifies all these problems.”

There is substantial evidence that policy decisions to harm and humiliate prisoners did not produce “excellent” intelligence, and these policies certainly did not win the war on terror. Rather, it generated a vast amount of false and useless information, and efforts to investigate that information wasted valuable time and resources. This evidence should silence assertions that such methods are a necessary “lesser evil.” Rejali writes, “Apologists often assume that torture works … [but if it] does not work, then their apology is irrelevant” (2007, p. 447).

Lessons from the US case confirm that torture cannot be employed with strategic precision; the anti-torture deontologists (see Chapter 1) were right: there is no such thing as just a little torture.

What the US lacked and desperately needed after 9/11 was human intelligence about al-Qaeda and affiliated organizations. But the decision to “take the gloves off” to compensate for the lack of intelligence had the reverse effects: It undermined the willingness of critical constituencies to cooperate, notably those in which terrorist organizations operate and populations to whom they appeal for support. By indiscriminately arresting so many people and by subjecting so many to violent and dehumanizing treatment, the quest for assistance in those communities, let alone hearts and minds, was damned. Torture squandered “we are all Americans” global empathy after 9/11 and invited righteous condemnation by informed citizens and allied foreign governments.

Perhaps the most important lesson is the falseness of the trade-off theory that human rights must be sacrificed for security when contending with the threat of terrorism. Pro-torture consequentialists argue that respect for the legal rights of suspects constrains the government’s options to protect the nation. However, a recent study by Walsh and Piazza (2009) finds that government respect for “physical integrity rights” (i.e. the “harder human rights” as discussed in Chapter 4) is consistently and significantly associated with fewer terrorist attacks. Respect for these rights, of which the right not to be tortured is supremely important, are so critical because their violation is so universally offensive. As Walsh and Piazza argue, respecting physical integrity rights by not torturing (or extra-judicially executing) suspects is more effective because it legitimizes counter-terror efforts and fosters active or passive support from crucial constituencies. Conversely, violations of the right not to be tortured confirm or increase the grievances that motivate people to oppose a government.

At a very high cost to victims, perpetrators and societies, the US case illustrates that no modern regime or society is more secure as a result of torture. On the contrary, its use spreads, its harms multiply, and its corrosive consequences boost rather than diminish the threats of terrorism and the number of people who count themselves as enemies.

Keeping torture illegal and struggling to enforce the right not to be tortured are the front lines, quite literally, of a global battle to defend the most universal right that all human beings can claim. If torture is legitimized and legalized in the future, it is not “the terrorists” who will lose but “the humans.” Should proponents of torture as a “lesser evil” succeed in regaining legitimacy for this odious practice, there would be no better words than George Orwell’s from 1984: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

[Excerpted from Torture: A Sociology of Violence and Human Rights, by Lisa Hajjar, by permission of the author. © 2012 Taylor & Francis. For more information, or to order the book, click here.]