Much like the ongoing revolutionary struggle in Egypt, this short piece is part of an in-progress work to chronicle the evolution of revolutionary art on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, also known as the “street of the eyes of freedom”—nicknamed as such since many protesters lost their eyes on that same street after being targeted by professional snipers during protests in 2011. (See previous articles on this subject by clicking here, here, here, here, and here. Also see interview with artist Alaa Awad on the subject by clicking here).

For a second consecutive year, Mohammed Mahmud Street witnessed intensive turmoil, and chronic violent clashes between demonstrators and security forces. Clashes ensued again in November 2012, ironically in the context of demonstrations that were organized to commemorate the previous year’s clashes of 19-24 November 2011, known as the Mohamed Mahdmoud Street battles. The clashes seemed like a farcical reenactment of those of the previous year, much like the Mohamed Morsi presidency and the Muslim Brotherhood, for many revolutionaries, are farcically reenacting the same policies, mindset, and discourse of the Hosni Mubarak regime.

Repertoire here might perhaps be one key concept that can help explain why the regular use of violence by authorities, and the recycling of the old regime’s discourses by the perpetrators of such violence have become dominant elements in the apparent counter-revolution led by the Muslim Brotherhood. Many anticipate that 2013 will be a decisive year for the wielders of power in their (recurrently violent) confrontations with the large segments of the population that are growingly losing faith in the Muslim Brotherhood. The hastily drafted constitution, and the overt threat it poses to basic principles of human rights and citizenship, perhaps underscore the Brotherhood’s desperation and angst over their faltering efforts to assert their control over—or as some call it, to “Brotherhoodize”—the state.

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 2 November 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 26 September 2012)]

Anticipation through repertoires is perhaps why many foresee a serious escalation of violence in the country after the “militias” of the Muslim Brotherhood fiercely attacked and tortured protesters opposed to Morsi by the presidential palace on 5 December 2012.

Repertoire once again, might explain too the insistence of revolutionary artists to repaint the same murals time and again, most notably the half-Mubarak-half-Mohamed Hussein Tantawi image discussed below. Based on the same language of the repertoire, one can view this corner (where Mohamed Mahmoud Street meets Tahrir Sqaure) as the site of an unfolding continuous dramaturgical performance that visually narrates the history of the revolution. Of equal importance is the public’s interaction with graffiti and murals [1].

During the second half of 2011 and early 2012, military authorities erected concrete walls to block protesters from entering the streets leading to the Ministry of Interior, which has been (and continues to be) the target of popular anger directed at police brutality and abusive practices. Many of these walls were later destroyed by protesters. But even when they existed, they were quickly filled by fantastic mutating graffiti and large murals. The incessant erasure of the paintings on the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street never stopped revolutionary artists from repainting them, sometimes with abundant displays of insults directed against the internal security, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), and the symbols of the old regime. This phenomenon has been met with a tremendous amount of interest by photographers and bloggers. As Egyptian authorities kept erasing the art by whitening the walls, artists responded with elaborated and sometimes improved versions of the previous paintings, until they excelled at the art of resisting, challenging, and insulting the counterrevolutionaries among with the wielders of power and their allies. Colloquial Arabic was often prominently displayed on the walls. No one within the centers of power was spared from sardonic jokes and mocking paintings. The internal security apparatus, the SCAF, the associates of the former regime, Muslim Brotherhood leaders, and President Morsi, all got their share of insults and satire.

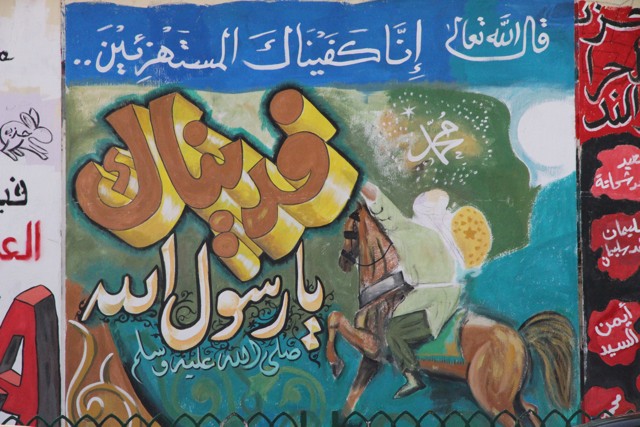

Street art became one main ways to reinforce and document the battlefields and street wars that occurred during the entire year. Such art offered its audiences one way of “being there” at these important events. In September 2012, Islamists tried their luck in the highly competitive field of street art. This was precisely after a highly controversial video insulting the Prophet Muhammed began circulating on social networking sites, sparking widespread protests throughout the Arab world, particularly in Egypt. In the wake of these protests, pro-Islamist activists attempted to conquer the walls with “Islamic graffiti”. Very quickly sardonic anti-Islamist graffiti spread throughout the area surrounding Tahrir Square.

[Islamic paintings on Mohamed Mahmoud Street walls. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 3 October 2012)]

[Islamic paintings on Mohamed Mahmoud Street walls. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 28 September 2012)]

The rest of this essay examines a number of snapshots that together form a brief diary of the intersection of Mohamed Mahmoud Street and Tahrir Square.

In many ways, this corner has become a crucial central nerve for Tahrir Square, being one of the main gates or entrances to the square and the site of numerous contentious confrontations and street fights.

After the outbreak of the revolution, almost all the corners of the streets in the area, including the intersection of Mohamed Mahmoud Street and Tahrir Square, became filled with easily mobile plastic chairs such that the space was quickly turned into a “street café” for the poor. For several months, it seemed that that those who sat at these cafes, gazing for hours at the life of Tahrir Square while sipping their tea, were watching a performance free-of-charge.

The Mohamed Mahmoud-Tahrir Square corner is also the site of a major metro station exit, which has become a sleeping area for the street children and old homeless men and women. During the winter, it is not uncommon to see several homeless children sleeping on the floor, seeking shelter by the wall of the metro station exit.

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 29 August 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 8 June 2012)]

The Half Tantawi-Half Mubarak Renewable Portraits

The Mohamed Mahmoud Street corner famously featured successive series of portraits, showing half the face of Mubarak combined with a variety of different political figures, evoking parallels between the deposed president and his successors. The portraits, which were produced by rabitat fanani al-thawrah (“The association of the artists of the revolution”), kept on being erased on a regular basis, presumably because the government must have felt utterly humiliated by such a negative portrayal. Yet despite successive attempts by Egyptian authorities to erase the paintings, the wall never stayed empty more than a few hours before it was repainted with the same images, usually with more detailed additions and variations. It is interesting to note that the same graffiti was later replicated on the walls of the Itihadiyya presidential palace in Heliopolis after the eruption of the massive demonstrations against Morsi’s controversial constitutional declaration, as well as the constitutional referendum that was hastily convened last December.

[Photo by Mona Abaza. Captured 21 February 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 25 March 2012)]

The half-Mubarak-half-Tantawi portrait, featured in the second photograph above, was captured in March 2012. On top of the painting are the words “The revolution continues.” The statement at the bottom reads illi kallif ma matsh, meaning “one [i.e. Mubarak] who delegated authority to someone [i.e. Tantawi] has not died.” This phrase rhymes with the popular saying illi khalif ma matsh, or “one who produced off-springs has not died.” Below the phrase is the following sentence: “A [military] council of shame and a lying Field Marshal.” Painted by Alaa Awad, the black panthers on the right hand side of the portraits symbolize the defenders of the revolution, who are ready to attack at any moment (see my interview with Alaa Awad). This same image has been erased and subsequently repainted several times in exactly the same size.

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 31 May 2012)]

Half-portraits of presidential hopefuls and former Mubarak aides, Amr Moussa and Ahmed Shafiq were later added to the same painting. To left of the image is a statement that reads: “I will never grant you any trust, neither will you rule me one more day.”

[Photo by Mona Abaza (26 September 2012)]

The photograph featured above was taken in September 2012 after that the wall was once again erased. The half-Mubarak-half-Tantawi portrait was repainted in a smaller size, with the addition of a portrait of Muslim Brotherhood General Guide Mohamed Badie. Below it is an image of a painter using his brush fresh with dripping paint as a weapon in confronting a policeman’s stick. A poem at the bottom reads:

“You, a regime scared of a brush and a pen

You were unjust and crushed those who suffered injustice

If you were honest, you would have not been fearful of painting

The best you can do is conduct a war on walls, and exert your power over lines and colors

Inside, you are a coward who can never build what was destroyed”

The Martyrs of the Revolution

[Clashes between security forces and protesters in Tahrir Square area. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured

23 November 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 30 November 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 30 November 2012)]

The photos above were captured on 30 November 2012, when Mohamed Mahmoud Street was deserted in the aftermath of the aforementioned clashes between security forces and protesters. The photographs on the floor are of the martyrs who died in the previous year in the November 2011 clashes that happened on that same street. The display of the martyrs did not last for long, and was removed a few days later.

The display appeared during the height of days-long confrontations on Mohamed Mahmoud Street between protesters and the police. The clashes had quickly escalated after seventeen-year old Gaber Salah, (famously nicknamed Jika) was shot dead. At the outset of these confrontations, revolutionaries put up a large sign at the entrance of the street clearly stating: “The entry of the [Muslim] Brothers is forbidden.”

[“The entry of [Muslim] Brothers is forbidden.” Photo by Mona Abaza (23 November 2012)]

[Clashes between security forces and protesters in Tahrir Square area. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 23

November 2012)]

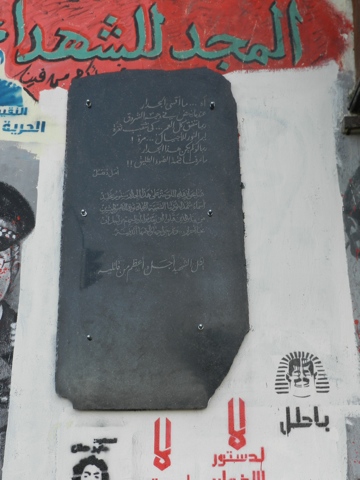

Three New Black Plaques on the Street Corner

[Paintings featuring anti-regime poem. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 8 December 2012)]

[Plaque featuring poem by Amal Dunqul. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 7 December 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 7 December 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 7 December 2012)]

On 7 December 2012 I met a man at the corner of the street who had used tiles and sand to create a protected space for plants in front of the Mohamed Mahmoud Street wall. Insisting on keeping anonymity and identifying himself as a “simple citizen of Egypt,” he told me that he was trying to create “a memorial space” for the martyrs of Mohamed Mahmoud Street battles by placing in that area on a daily basis plants and icons commemorating the martyrs of the revolution. Together with a group of people, he decided to hang on the wall three plaques of black marble. The small plaque beneath the plants read: “From the people of Egypt”. On top of the half-Tantawi-half-Badie-half-Mubarak portraits, another black stone displayed a Quranic verse. Another black plaque was nailed to the other side of the wall. Dedicated to the martyrs of the January 25 Revolution, it contained a poem by the late Amal Dunqul. The poem described the harshness of walls that paradoxically inspire and generate hope for finally seeing the light of freedom.

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 8 December 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 8 December 2012)]

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 8 December 2012)]

In the spirit of the inconclusiveness of Egypt’s ongoing revolution, I will refrain from offering a conclusion to this essay. However, I would like to close by saying that, as long as Egypt’s wielders of power continue to undermine calls for revolutionary change in the country, the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street, and many others, will continue to offer an arena for the lively expression of political dissent and resistance. The dramaturgical performance that Mohamed Mahmoud Street is witnessing today will continue to unfold. The play is far from over.

___________________

[1] For an interesting reading of the revolution as a “performance” and as dramaturgy, see Amira Taha and Christopher Combs “ Of Drama and Performance: Transformative Discourses of the Revolution” in Translating Egypt´s Revolution, The Language of Tahrir, Edited By Samia Mehrez (AUC Press, 2012), and Jeffrey C. Alexander Performative Revolution in Egypt: An Essay in Cultural Power (Bloomsbury Academic, London, New York, 2011).