On 24 January 2011 – a day before the arc of Egyptian history would be altered – the film Microphone was screened. Microphone documents Alexandria’s pre-revolution underground scene of artists and musicians fighting a passive oppression that suffocates their ability to nurture their creativity. Khaled (played by Khaled Abol Naga), who has returned to Egypt from the US, wishes to aid the youth by providing them with a venue and funding for nurturing their talents. In one scene, Khaled is conversing with an official at the state’s cultural office to request support for his project. The dialogue proceeds as follows:

Official: What is this graffiti? Is our role to pollute the walls or to clean them?

Khaled: “Graffiti is an art, the whole world acknowledges it. We have to encourage the youth in their pursuits”

Official: “Is this not transgression against people and properties, and visual pollution?

Khaled: “What about the campaign posters littered around the country’s walls, isn’t that visual pollution as well?”

Official: “No, that is something and this is something else. Election campaigning is part of our democratic process”

To the dumbfound look of Khaled who - frustrated enough by red tape - now is expected to digest a bureaucrat’s talk of “democracy” in Hosni Mubarak`s Egypt

Prior to the revolution, Alexandria’s walls were largely Soviet-esqe and barren. Artists who did attempt to paint the walls, like Aya Tarek (featured in the film) and Amr Ali (not the author of this piece), were often stopped by the police or reported by onlookers suspicious of their novel activity. Fatma Hendawy, a curator who started on the street scene before the revolution, notes that one way to circumvent these obstacles was to go through the Goethe Institute to use its diplomatic muscle to define joint German-Egyptian art projects. Yet as Fatma laments, such institutes inadvertently stump your creativity in order to cater to their bilateral agendas.

In the months following the 2011 Revolution, I took to cataloguing the artwork that blossomed and inspired me to believe that the public space was gradually being reclaimed by society. I am no artist; however, I take the position of the “public” and write on the art in the context of the socio-political dynamics and nuances that influence societal perceptions of street art. Specifically, this essay attempts to tell the story of the past two years purely through artwork from the streets of Alexandria. For Cairo, I highly recommend the large collection of Suzee Morayef who, on her blog, offers great analyses on street art that is prolific through the capital’s streets. Also Mona Abaza, professor of sociology at the American University in Cairo, has penned brilliant pieces on the artistic narration of the revolution.

Triumph Over the Pharaoh (Early 2011)

The stepping down of President Hosni Mubarak gave way to a social euphoria that seeped into the street art that was governed by the mindset “The power of people is stronger than the people in power.”

[From the Roushdy neighborhood of Alexandria: “25 January: the birthday of the Egyptian People.”

Shoes being thrown at Mubarak. Photo by Amro Ali]

[Roushdy: Revolutionary motifs. “Egyptian and proud.” Photo by Amro Ali]

[A tank bearing “Freedom.” Such pro-military slogans are something the revolutionary camp would live to regret.

But pro-military feelings were so strong during the first half of 2011 with an often rebuttal: “The army is us, they

would never betray us.” Later distinctions were made between army and the military council. Photo by Amro Ali]

[“Youth’s Revolution”: The youth felt they had ownership over this revolution,

and everything was made to classify it as such. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Alexandria’s Stanley neighborhood: “The People,” the eternal cry of the revolutionary

voice that would follow it up with “Demand the fall of [insert your current oppressor here].”

Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Stanley: “The Martyr screams, where are my rights oh country.” The man’s image is

inspired by a 2006 torture video of a bus driver, Imad El-Kabir. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Alexandria’s neighborhood of Smouha: Late Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s famous line:

“Lift your head oh brother.” It is unusual that Nasser is painted over the very monarchical flag he did away with.

However, it also reflects Alexandria’s relation to both. The city’s middle and upper-middle classes have had,

anecdotally, a strong fondness for the pre-1952 Egypt more than any other Egyptian population center.

However, Nasser was born in the Alexandrian outskirt of Bacus, and his economic policies gave him

a strong loyal following in working class districts. Photo from Alexandria Graffiti Facebook page]

[From Alexandria’s neighborhood of Mahtet el-Raml: Drawn on the walls surrounding the Italian consulate,

painting shows an exchange between an Egyptian and a foreigner. “Egyptian: How’s your salary overseas?

Foreigner: We get $3000/month + $500 “instead of” [“badal” or allowance for] meals + $1000 instead of health insurance.

I make a total of $4500/month. Egyptian: After the revolution I make 700 Egyptian pounds.

Foreigner: And these are “instead of” what?? Egyptian: These are instead of me becoming a bum!”

Photo and translation by Tariq Fahmy]

The Dawn of A New Era (Early- to Mid-2011)

Once upon a time in Alexandria’s Stanely area, there stood a beautiful mural facing the sea dedicated to the key figures of the revolution. It was painted by students from the College of Fine Arts, and to me it magnificently captured the hopes and aspirations of Egypt’s youth. The faces of the martyrs told a story that they did not die in vain. I often felt this art was too good to be true, and that it faced two primary enemies. The first is human censorship, and the second being nature’s censorship, namely the salt from the sea that tends to erode the paint. The former came quickly enough. Fatma tells me that all of a sudden in early 2012, the owners of the place on which this mural was painted did not like it anymore. But she points to something deeper than that. Their decision came a few months after the posting of a new chief of security directorate for Alexandria. This is when the security forces started to regain their composure after being knocked off balance during the 2011 eighteen-day uprising. Fatma says “He [the new chief] wanted to control the streets again, and painting over it was to send a strong message to the artists and intellectuals: ‘Don’t dream too high.’”

[From Alexandria’s neighborhood of Stanley: Khaled Saeed, Egypt’s “chief martyr” and the spark of

revolution, as part of a mural with other key figures. Photo from Alexandria Graffiti Facebook page]

[Revolutionary martyrs. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Alexandria’s neighborhood of Stanley: Revolutionary martyr, Ahmed Bassiouni. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Roushdy: “Free for Ever.” The word freedom (in Arabic or English)

was the most commonly used word on walls. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Stanley: “Egypt is the mother of the World” a reassertion of national

pride after years of Mubarak’s lackluster performance. Photo by Amro Ali]

The Alexandrinization of Public Space

Alexandrian artists are heavily influenced by the legacy of the city’s two brothers Adham and Seif Wanely. whose paintings of “daily life in Alexandria, the sea, the fishermen`s boats, and the beauty of streets and squares” helped to nurture an Alexandrian identity. More so, the prominent artist Mahmoud Said (1897-1921), who heralded from an aristocratic Alexandrian family, was at the forefront of painting different layers of Alexandrian society. The post-revolution’s art scene saw various Alexandrian motifs painted by the experienced and less so.

[From Stanley: A Roman soldier, symbolizing the city’s Greco-Roman heritage,

is painted between “Freedom” and “25 Jan,” and above “Alexandria.”

Photo by Amro Ali]

[From East Alexandria: An unfinished painting of a ship bearing the Egyptian colors.

Ships and sea are some of the most common paintings seen around Alexandria, given their

primary historical and cultural association with the city.

Photo from Alexandria Graffiti Facebook page]

[From Alexandria’s neighborhood of Ibrahmeya: A boat is painted on a tunnel entrance for pedestrians.

The boat also directly faces the sea. Photo from Alexandria Graffiti Facebook page]

[From Stanley: Citadel of Qaitbay stands between a Church and a Mosque. The city (as much as the rest of the country)

was traumatized following the bombing of the Church of the Saints in Sidi Bishr at the start of 2011.

Muslim-Christian unity themes became a common sight around the city. Photo by Amro Ali]

[Kamp Shezar: The close proximity to sea (ten meters away) and Citadel of Qaitbay painted in the

background give the impression of an Egyptian mermaid protruding her head out of the bay. Photo by Amro Ali]

[Alexandria’s neighborhood of Cleopatra Hamamat: In his home district, there is no shortage of

Khaled Saeed images. This one paints a more respectable citizen.

Photo from Alexandria Graffiti Facebook page]

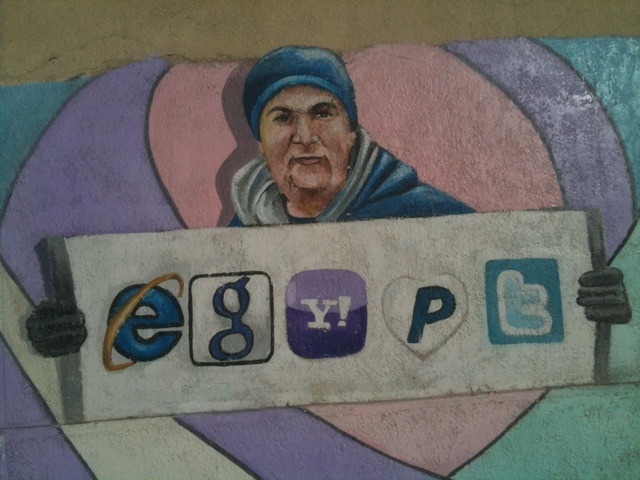

“De-Friending” the Status Quo: Internalizing Social Media

Social media formed a crucial component of youth identity that it was elevated, if not deified, to synchronize with the youth revolution discourse.

[From Stanley: Inspired by a man unfurling a paper of social media icons during the revolution. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Roushdy: Google featuring Alexandrian Sayed Darwish, the father of Egyptian popular music. Photo by Amro Ali]

[From Roushdy: Facebook icon. Photo Amro Ali]

Seeking A De-SCAFinated Egypt: The Army and People Are No Longer One Hand (October 2011 – June 2012)

The October 2011 Maspero massacre hastened the demise of the people-military love affair. More so, the Mohamed Mahmoud clashes in November 2011 represented the heightened anti-military council protests.

[“The thugs are the army.” Inspired by Carlos Lattuf cartoon. Photo from Alexandria Graffiti Facebook page]

Imagination Continues

As it stands, Alexandria’s public walls are covered more in soccer Ultras amateurish graffiti and sporadic anti-Muslim Brotherhood artwork. If one compared the street art scene in Cairo and Alexandria in 2011, the number of creative works, I argue, tilted in favor of the latter. Yet 2012 tilted in favor of the capital due to the key battlegrounds of Tahrir, Maspero, Abasiyya, Itihadiyya, and others, which have drawn artists to the capital to “wage war” with their paintbrushes. While in Tahrir, I asked a friend of mine, Alaa Awaad, a native of Mansoura (and makes regular journeys to Cairo from Luxor, where he teaches): “Does it not bother you that you paint during the day, then someone comes at night and desecrates your work?” His response was profound: “Let them do it. This only means I will come back and paint again. This revolution is ongoing.”

[From Stanley and Cleopatra Hamamat: I often find Khaled Said’s iconic face to be a barometer of the public mood.

The above are different locations and different styles of painting of course. But the first (left) one gives a

progressive outlook to hope for a better future, the second (right) restores the struggling, revolutionary Khaled.

Photos by Amro Ali]

[From East Alexandria: In this photo I snapped in early 2011, a passerby gives money to a beggar under the sign of freedom.

It is telling in that there is an Egypt that seeks freedom from repression, and another seeks freedom from poverty.

Photo by Amro Ali]

Fatma nicely captures the soul of the city’s artistic endeavors: “My dream is to deliver art to the people of Alexandria, not the elites. We need to break the myth that art is for high society. I feel I have achieved a bit of that dream. In the early days, the public would stop us in the street, very simple people, even street kids, asked if they could help. They saw beautiful colors for the first time and wanted to be part of it.”

As we enter the second anniversary of the revolution, Egypt needs to find a way to tell the art scene, “It is okay to dream too high."

![[Revolutionary martyrs painted on walls of Alexandria. Photo by Amro Ali]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Cover.jpg)