Pick any mid- to upper-class residential project in Lebanon and you will more often than not find the floor plan featuring a small room with the label of “maid’s room.” Through ubiquity, this label and the architecture it signifies have long passed the stage of normalization not only in Lebanon but also in other parts of the Arab world such as Qatar, UAE, and Saudi Arabia where middle and upper class families rely on cheap manual labor in the form of predominantly female foreign workers to maintain households. The Lebanese case, however, serves as one where (a) land per capita is one of the lowest in the world and (b) a neoliberal construction law that is deliberately relaxed in order to favor the monetary profit of the developer at the expense of the quality of the built environment. Private apartment blocks and bourgeois villas are primary sites where a veritable combination of local taste and maximum land exploitation, with a backdrop of racist law, results in workers’ spaces that are at best substandard and often gravely oppressive. In light of recent and ongoing demonstrations by domestic workers in Lebanon and of their growing struggle to push the Lebanese government to ratify the International Labor Organization Convention 189 and abolish the Kafala system, it is imperative to call out certain laws and practices in contemporary Lebanese architecture as concrete manifestations of institutional racism against foreign domestic workers, in both the public and private sectors. Within Foucault’s more general and elusive concept of heterotopia, I will argue that the maid’s room qualifies as a subgroup, the "heterotopia of deviation."

[Figure 1: Three workers’ rooms. The photos are stitched panoramas:

the only way to capture the entirety of the rooms due to the very confined space. Photos by Bassem Saad]

Legal Frameworks: Kafala System and Lebanese Construction Law

For those unfamiliar with the workings of the domestic worker industry in the Arab world, the sponsorship (kafala) system places foreign workers, usually hailing from Ethiopia, India, Philippines, Bangladesh, or Nepal, under the sponsorship of a citizen or agency while giving the sponsor control of the worker’s working conditions, mobility, and legal documents. If an irreconcilable conflict arises between the two parties, the worker faces risk of losing their legal status in the country and deportation. In the case of domestic workers, passports are often withheld from the women by the families they serve, supposedly for the fear of runaway theft. Although a domestic worker might cycle in a day through the roles of housekeeper, cook, babysitter, caretaker of the elderly, gardener, dog walker and/or “ethnic” hairstylist, it is widely held by Lebanese patrons that a domestic worker’s job is not as demanding as a traditional full-time job and thus need not have a fixed number of hours of rest per day. The wage itself notoriously depends on the worker’s nationality in a manner akin to how the price of a restaurant dish depends on the breed of livestock employed. This starts at 150 US dollars a month which is around 400 US dollars below the national minimum wage, a fact rationalized by referring to the origin country’s average income. Moreover, and as can be inferred, Lebanon’s outdated labor law does not include domestic workers. This exclusion of domestic workers’ labor from the scope of Lebanon’s labor law is mirrored by the exclusion of worker dwelling spaces from the broad category of spaces intended for human habitation.

The legal framework is defined by the Lebanese Construction Law which contains several clauses relating to domestic worker lodging. First, it should be noted that the Law refers to domestic workers’ lodgings as “servants’ rooms” and even goes so far as to refer to the “servant” in one particularly revealing instance in the feminine form. This worker room type is chunked together throughout the text with other types such as storage rooms, laundry rooms, and outhouses that are primarily not designed to contain people for extended periods of time. The primary purpose of this grouping is to delineate the room types that do not factor into the general floor area ratio (translation from Arabic: “general investment ratio”) so as to allow developers to maximize the areas of rooms that add market value.

As a result, there exists a clause that sets the maximum area of the maid’s room and each of these types at eight meters squared. Another purpose of this grouping is to exempt these rooms from the obligation of having “unobstructed” windows. The law becomes truly problematic when it explicitly states that rooms designed to be inhabited by people are required to have unobstructed windows, a paragraph before it excludes the worker’s room from this category. In a nutshell, the maid’s room does not factor into the exploitable area of a plot, must not exceed eight meters squared and is not required to have viable windows.

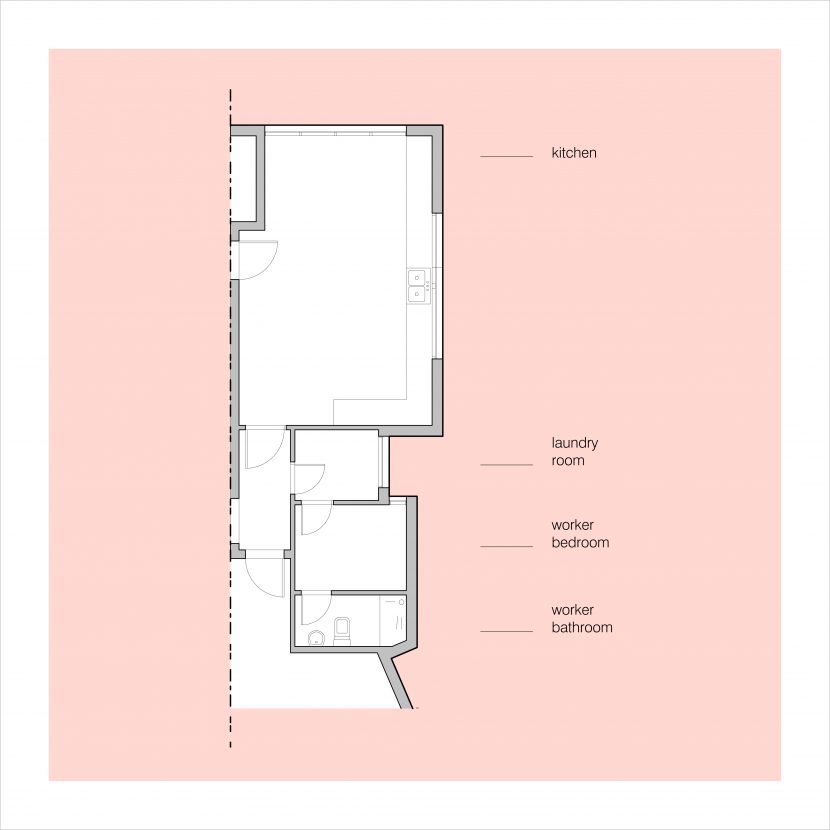

[Figure 2. Image by Bassem Saad]

Professional Attitudes from Academia to Marketplace, Two Case Studies

In terms of professional practice, aside from the cut-throat exploitation of surface area, the prevalent attitude among clients, architects, and even some architecture instructors at the country’s leading architecture schools holds that the domestic worker and their dwelling spaces belong to the category of non-aesthetic service-related elements in a design that must be cleverly concealed behind several layers of architecture to ensure that they are rendered as inconspicuous as possible. The result is a very well-defined typology consisting of a room averaging around five square meters in area, sometimes windowless, that is only accessible through the kitchen.

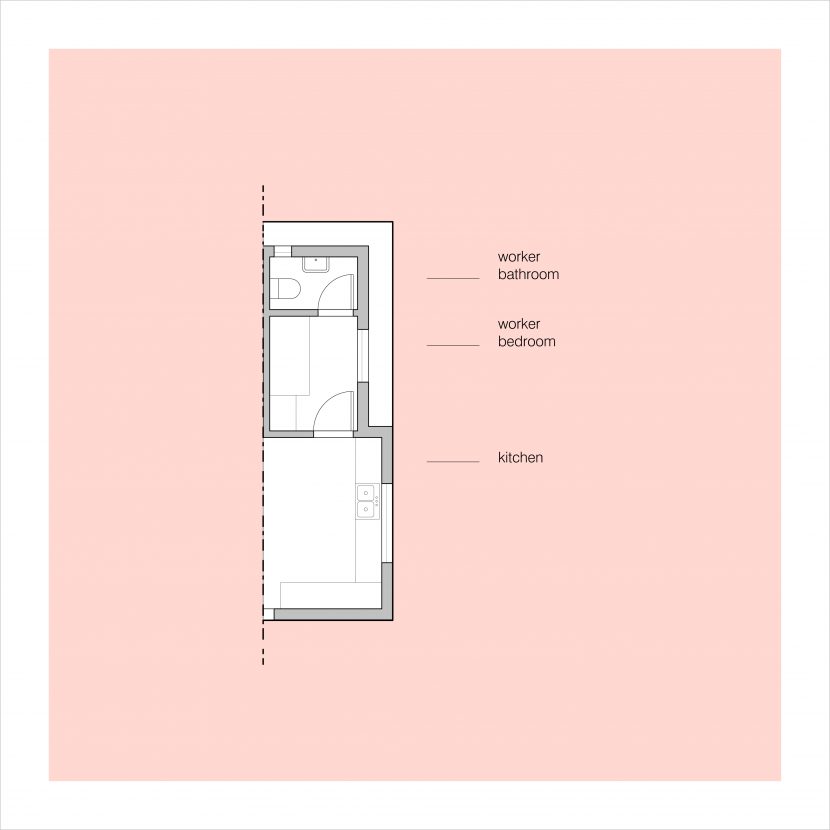

The plans in this article show two examples from ongoing projects that fall at different ends of the spectrum of current practices. The first (Figure 2) is at the generous end; the architect has managed to provide a decent window and an area of 5.2 square meters (out of a total of 187 square meters, which is around 2.87 percent). This is unfortunately the current best-case scenario that a worker can look forward to in newly constructed projects. The second case however is better illustrative of the sort of dehumanizing design gestures that revel in making the maid’s room as invisible as possible (Figure 3).

The corridor leading to the worker’s room is given doors at both ends and it leads only into the laundry room and not directly into the maid’s room. The wall of the laundry room is offset to the inside in order to give the worker’s room an indirect ( less than 50cm-wide) window that does not face the garden. The room is 2 meters by 2.6 meters, with a surface area of 5.2 square meters (out of a total of 531 square meters, equating to less than one percent).

[Figure 3. Image by Bassem Saad]

This particular case is by no means an anomaly but adheres to current informal Lebanese conventions surrounding the typology. The resultant architecture is an example of gendered racism in at least two ways: on the one hand its closefisted allotment of space and on the other its forced invisibility behind multiple layers of insidious architectural barriers such as sealed corridors and narrow windows.

Maid’s Room as Heterotopia of Deviation and the Racialized Laborer

The concept of heterotopia was introduced by Michel Foucault in a lecture in 1967 and shortly dismissed by him. It was however quickly latched onto by urban and spatial theorists interested in studying spaces that deviate from an otherwise homogeneous and accepted totality. A misgiving about the term voiced by David Harvey, has to do with its ill-defined scope and its ability to be applied to spaces such as the commercial cruise ship that preclude any emancipatory potential. These shortcomings are usually associated with the term when it is used in a liberatory sense, as a site for the creation of new and different relations. Here, I will focus on a particular subgroup of heterotopia which is the heterotopia of deviation.

A heterotopia of deviation is defined as a space for an individual whose “behavior is deviant in relation to the required mean or norm”, in this instance that of the middle- to upper-class Lebanese household/nuclear family unit. The migrant worker is let into this fragile site, automatically acquiring the status of deviant once discrepant cultural and domestic norms are identified. This foreign body is then referred to its designated container, the one designed while bearing in mind its occupant’s identities and class. This container’s siting within the house and its enclosure engage more of the heterotopia’s characteristics: controlled openings and containment of content that is not to be made public. The convoluted circulation leading into these rooms, by kitchens, laundry rooms, and narrow corridors, unambiguously separates them from the humdrum rhythms of the full-status inhabitants, attaching them as appendices to service areas. And although the absence/inadequacy of windows in these rooms is often dictated by the market-driven rationing of space, they are sometimes deliberately given narrow wedges of natural light as shown earlier when the building’s façade faces a street or a garden, in an aesthetic effort to conceal a less-than-ideal affair. The maid’s room is ultimately suspended in invisible isolation from both the interior and the exterior; the racialized and gendered body is forced into becoming a troglodyte in the heart of the household.

This invisibility is perhaps the most sinister component of the typology. What is compartmentalized does not disrupt the daily turnings of the residents and is quickly normalized. The households I visited (most happened to be in apartments, none were in self-built villas) in search of photographic documentation were composed of people who were no more or less discriminatory than the general population; the pervading attitude was one of casual resignation. Whether this resignation is due to a silenced ethical dissonance and whether this dissonance existed in the first place is up for debate. Less may be said of the architects who oscillate between being complicit by uncritically catering to racist demands and actively employing creative architectural thinking to further them. These architectural trends are very challenging to counter due to well-engrained practices, the definite nature of the architectural act, and the natural lifespan of buildings. They need to be acknowledged as grievous mechanisms of oppression propagated by developers, clients, and architects and included in anti-racist efforts and law reform initiatives. Meanwhile, Lebanon’s discriminatory inclinations are literally being set in stone, clad in luxury Carrara marble, and will live on as artefacts of this particular form of gendered racism and worker exploitation long after regulations improve and the labor law is reformed, if ever.

[This article was originally published on Failed Arcitecture.]

![[Worker`s room. Image by Bassem Saad]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Screen-Shot-2016-11-29-at-11.28.26-1-1010x400-1480416597.jpg)