In June 2018, the rescue ship Acquarius (jointly operated by SOS Méditerranée and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)) endured nine days of difficult navigation as both Italy and Malta denied the vessel entry after rescuing more than six hundred migrants. It was eventually allowed to safely disembark its rescuees in the Spanish port of Valencia. The episode, one of many in a larger saga, points to two important (even if difficult) lessons. First, the crisis in European governance of migration and asylum is far from over, notwithstanding the wishes of some that it would be solved through externalization to Turkey and Libya. Second, the closure of the Mediterranean space to undocumented flows of people continues, even when such flows are technically “mixed”—meaning, they potentially include persons that would be entitled to international protection. On paper, this closure to undocumented flows was to be offset by a gradual expansion of legal migration channels. This is what the European Union has been promising to southern Mediterranean neighbors for years. However, little of this compensatory logic has materialised so far, and in the past few months, things seem to have even gotten worse.

The Promises of 2011 vs. Actual Visa Trends

During the two years of 2015 and 2016, cross-Mediterranean refugee flows have topped the European Union’s migration policy agenda as well as wider political agenda. The issue of refugee flows has been so dominant as to monopolize the EU migration policy agenda, thereby marginalizing other issues—most notably government authorized short-term mobility and labour migration (i.e., travel through the visa system).

Non-EU countries to the east and the south of the Mediterranean have not been exempted from this trend. As a matter of fact, in the wake of 2011 uprisings, the European Union had proclaimed a strategic orientation that sought to support political and social change in the region. The announced strategy included a more flexible approach to the management of migration and mobility. For instance, in an important communication issued in March 2011, the European Commission and the European Council jointly announced that:

In the short-term, the Commission will work with Member States on legal migration legislation and visa policy to support the goal of enhanced mobility, in particular for students, researchers and business persons. [ . . . ] In the long-term, provided that visa facilitation and readmission agreements are effectively implemented, gradual steps towards visa liberalisation for individual partner countries could be considered on a case-by-case basis.” (COM(2011) 200 final, p. 7)

But seven years later, little to nothing of all this has materialized. The most direct indicator of this lack of an actual policy shift—away from traditionally restrictive approaches toward a more liberal one—can be found in visa issuing trends. Italy’s visa policy provides a relevant example, since one of the main receiving states of cross-Mediterranean immigration in the European Union, and the third largest visa issuer of the Schengen area (with about 1.8 million visas granted in 2016, trailing Germany’s 2.3 and France’s 3.0 million visas granted).

[Table: Key indicators in Italian visa policy toward non-EU Mediterranean and Middle East countries (2010-2016). Source: Annuario Statistico Ministerodegli Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, various years.]

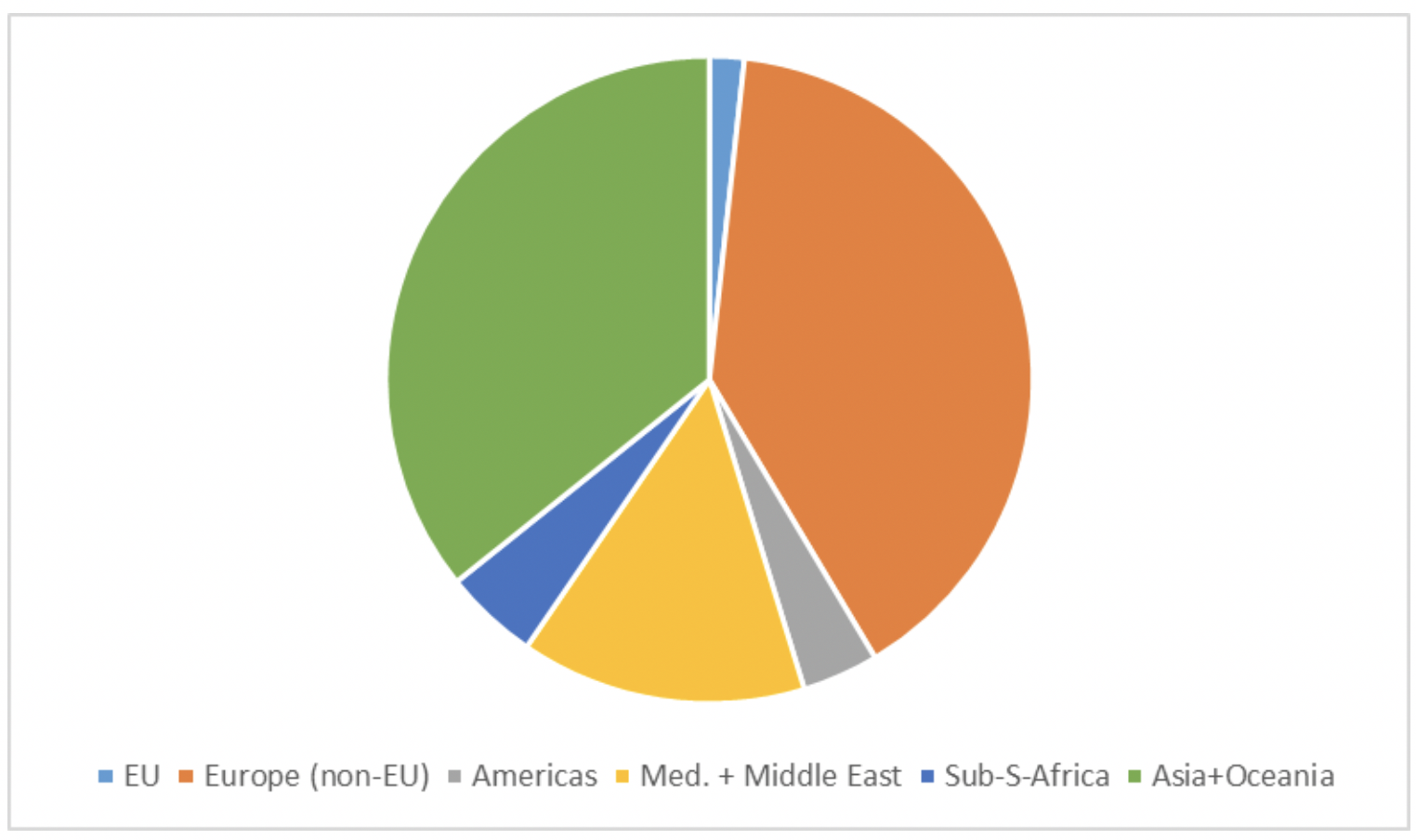

As shown in the above table, the volume of annually granted visas by Italian consular authorities to nationals of Mediterranean third countries has indeed moderately grown in absolute terms (although not as a percentage of total granted visas) in the immediate aftermath of the Arab uprisings. But in the following two years (2015 and 2016), this growth has stopped altogether. As a result, in 2016 (the last year for which disaggregated figures are available) only 14.3% of the total number of Italian visas were granted to nationals of Mediterranean countries. This contrasts with the much larger numbers of visas granted to applicants from Asian (mainly Chinese) and Europe (mainly Russian nationals).

[Graph: 2016 distribution of Italian visas by areas of origin.

Source: Annuario Statistico del Ministero degli Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, 2017).]

Some have justified the lack of a significant increase in visa volumes for Mediterranean and Middle East states with reference to the tit-for-tat and top-down logic of the European Commission. Accordingly, the lack of liberalization of visa issuing is a function of the failure of social and political change to materialize in countries. Yet such claims ignore the fact that legal mobility and migration channels remained almost as narrow as before for the one country that the European Union has praised as having undergone a more substantial democratisation path: Tunisia. In 2010, the year before the revolution against the Ben Ali regime, Italy granted 12,269 visas to Tunisian nationals. In 2016, the figure went up to 17,752. This is not a negligible increase, but it is a far cry far from the two-step “more for more” approach (facilitation in the short term, liberalization in the long one) that had raised so many hopes back in the immediate aftermath of Ben Ali’s fall. post-revolutionary years.

Readmissions of Undocumented Migrants in Exchange for Documented Admissions

The apparent EU policy shift away from promises of gradual liberalization toward further securitisation of migration and mobility now seems to be intensfiying.

The apparent EU policy shift away from promises of gradual liberalization toward further securitisation of migration and mobility now seems to be intensfiying. In the March 2018 EU proposal to amend the Visa Code, we can glimpse how a new approach to visa policy is being envisaged. The incentive-based approach of 2011 now seems long forgotten. Negative conditionality is the order of the day: Non-EU Mediterranean countries are expected to readmit undocumented migrants and doing so will allegedly be reciprocated by the European Union in its visa issuing practices. In this regard, EU institutions and members states are increasing pressure to force Mediterranean countries to comply with the EU readmission strategy. It is notable that this strategy does not just entail readmission of their own citizens, but also of third-country nationals proven to have transited through their territories. As the EU Commission put it:

The Commission is proposing to introduce a new mechanism to trigger stricter conditions for processing visas when a partner country does not cooperate sufficiently on the readmission of irregular migrants, including travellers who entered regularly by obtaining a visa which they overstayed. If needed, the Commission, together with Member States, can decide on a more restrictive implementation of certain provisions of the Visa Code, including the maximum processing time of applications, the length of validity of visas issued, the cost of visa fees and the exemption of such fees for certain travellers such as diplomats.

The outlook is not much better in the case of documented immigration for economic purposes. In this regard too, the strategic orientation of the European Union has visibly changed. Since the late 1990s, the “external dimension” of EU migration policies had formally been committed to a “comprehensive approach,” whereby cooperation in the field of migration controls would be balanced with a greater openness on legal migration. On paper, this was still the case with the European Agenda on Migration—launched in May 2015 (COM(2015) 240 final), right before EU officials began to describe the migration flows as being at crisis levels. That encompassing strategic blueprint was built upon “four pillars to manage migration better,” namely: (1) “reducing the incentives for irregular migration;” (2) “border management – saving lives and securing external borders;” (3) “Europe's duty to protect: a strong common asylum policy;” and, last but (allegedly) not least, (4) “a new policy on legal migration.”

Labor Migration Confined to Pilot Projects

But if one now looks at the structure of the May 2018 “Progress Report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration” (COM(2018) 301 final), the original comprehensiveness of the EU migration policy agenda seems forgotten. This latest document is almost entirely devoted to illustrate the different components of a very articulate prevention and containment strategy for “mixed migration flows.” As for documented migration, it is confined to a final section consisting of a miscellaneous of “Relocation, Resettlement, Visa and Legal Pathways.” It is only in this context that legitimate migration for working purposes finds a (still merely tentative) place:

The Commission has continued to support Member States to develop legal migration pilot projects with selected African countries. On 16 April, a call for proposals was launched under the Mobility Partnership Facility. This call comes in addition to an EUR 15 million regional programme to support legal migration in the North of Africa region to be adopted under the EU Trust Fund for Africa during the next North of Africa window Operational Committee meeting. (p.18)

These pilot schemes should benefit selected third countries (including some in the Mediterranean region) and they should address both low-skilled and high-skilled labor migration, with a view to encourage circular migration. Apart from this, however, little is known. The European Commission understandably wants to be sure of the political will and practical commitment of key member states before generating too many expectations in potential partner countries.

This latter policy development, however exploratory, is certainly welcome. But it is definitely far from enough. This is particularly so, for southern Mediterranean societies, that with few exceptions have so far not been able to recover from the global economic crisis and catch the train of global economic recovery. The lack of progress on the issue also matters in explicitly political terms. In the absence of credible incentives such as expanding documented migration and mobility, regional governments might be tempted to fall back entirely into the role of “delegated border guards” on behalf of the European Union as they used to be before 2011. That, of course, entailed disastrous outcomes that are still before us.

[Author’s Note: This article benefits from research carried out in the framework of the MedReset project, a consortium of research and academic institutions focusing on different disciplines from the Mediterranean region to develop alternative visions for a new Mediterranean partnership and corresponding EU policies. The project is funded under the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Programme for Research and Innovation]